The Politics of Art

Art and politics may seem like strange bedfellows but nowhere do the two embrace more intimately than in the cartoon.

Last week, in London, I visited the National Gallery to see a fascinating exhibition of portraits by Lorenzo Lotto, one of the greatest portraitists of the Italian Renaissance. He depicted men and women sitting alone or in compositions of two or three, and equipped his paintings with a rich symbolism that imbues them with a compelling psychological depth.

Lotto’s sitters, among them clerics, merchants and humanists, are often surrounded by objects which, together with the attire and jewellery of his sitters, hint at the status, interests and aspirations of his subjects, adding social and political meaning to each work. At the centre of his rather melancholic social commentary is the Portrait of Andrea Odoni: a rich merchant and collector of paintings, sculpture and antique vases, as well as curiosities such as petrified serpents and rare shells. He wears a rich and dark mantle, trimmed with a luxurious fur collar, and has a gold chain around his neck. In one hand he holds a crucifix, and in the other a sculpture of the Ephesian Diana.

In my lectures on fragments and the cult of ruins, I have often used this portrait as a prelude and introduction to the Modernist invention of abstraction. Michelangelo was at the centre of this milestone in western art history, symbolised by the myth of the Torso of the Belvedere. He is undeniably the artist who best expressed the marriage of Neo-platonic thought and Christian doctrine that is represented in this painting. But with Lotto – for whom Odoni is the personification of the cultured milieu of merchants and bankers who spearheaded the spread of Humanism – modern psychology was born.

From Lotto onwards, all the way to Expressionism, to Meidner’s Ich und die Stadt and beyond, the portrait became more than a mere record of a likeness. It is a document that charts the subconscious. The relationship between man and his physical, social and political environment is embedded in it. The portraitist is not only a poet imitating and recomposing Nature, but has also taken on the role of political and social commentator.

Shelley wrote that “the most unfailing herald, companion and follower of the awakening of a great people to work a beneficial change in opinion or institution, is poetry.” I remember reading Marilyn Butler’s Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries about English Literature around the time of the French Revolution. It blew me away with its intricate description of the relationships between English writers, critics, editors and journalists who were “peculiarly political”.

Who would have thought that the sublime descriptions of the elements and the moody landscapes in Shelley’s beautiful verse were more than a metaphor for the individual soul and concealed a precise political message aimed at the renewal of a staid society? No poet of the Romantic period, even the most apparently apolitical like Keats, spared any political effort. The Romantics’ favourite theme of the bloom of individual consciousness in the face of a destructive natural cosmos was none other than a Liberal clarion call for the masses.

Young writers such as Hunt, Keats, Shelley, Scott and Peacock consolidated the role of the poet in society as a chronicler and revolutionary, a tradition that extends all the way, in recent times, to Lennon, Cohen and Dylan. Art and politics may seem like strange bedfellows, but nowhere do the two embrace more intimately than in the cartoon, a genre that blossomed as the winds of change swept across Europe following the French Revolution.

In the middle of the 19th century, Punch magazine inaugurated a new period where satire, caricature and humour, contained in images describing the political climate of the moment, insinuated their way into our lives and became a daily presence, influential and powerful enough to put in motion an engagement as tragic as the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

The art of Sebastian Tanti Burlò has its seed in this tradition. His work in local newspapers is an expressive and satirical take on both the underhand – and very public – goings-on of a tiny post-colonial, post-modern population that has clumsily been trading its authentic catholic-community values for a deterministic, commercial drive for material wealth. Its spiritual savings have been withdrawn from the nation’s coffers, Sebastian seems to say, to be converted into a new currency consisting of the numbers of bedrooms and square metres of total ugliness.

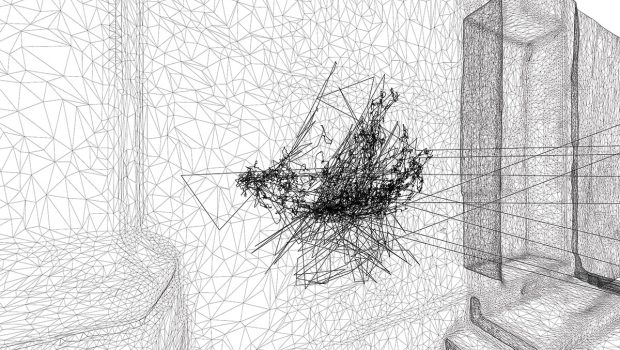

His new body of work consists of a series of large canvases, portraits which, true to the axiom that architecture is the mirror of the soul of a nation, represent the human equivalent of the current urban landscape. Here is a group of stereotypical members of the community that he depicts, critically but affectionately; Sausage People he calls them, gathered around the table, like a ship of fools, to console themselves about the loss of looks and love, of friends and taste and dreams and all the beautiful things of life.

They are divining new ways of raising that all-important, high-as-can-be number in the bank which, they erroneously believe, can make up for all that unhappiness and loss. It can buy a pair of Fendi sunglasses and a Ralph Lauren polo shirt and silk Yves Saint Laurent ties, brands that crowd their portraits like the objects that populate Lotto’s canvases. Unlike Lotto’s humanistic melancholy, though, the bright colours and rich attire here conceal a deep-rooted sadness. It is a kind of Vanitas because if loss and pain are an inevitable part of life, the artist seems to be telling us, we need to find more lasting and sustainable forms of redemption.

Portrait of Andrea Odoni by Lorenzo Lotto is in the Royal Collection of the United Kingdom and was exhibited at the National Gallery in London earlier this year. The Last Dinner by Seb Tanti Burlò, will be on show at Risette, 81 Old Theatre Street, Valletta, until 30 April.