Black Lives, Parisian Picnics and Art Matters

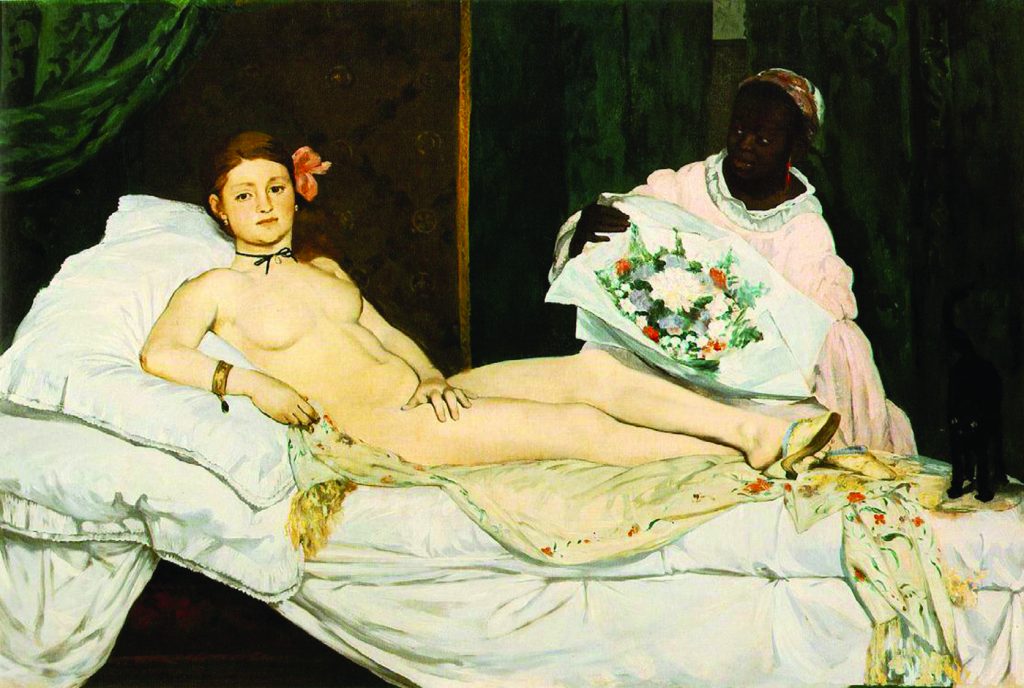

The focus is on the hitherto ignored figure of the black servant, who, rather than being perceived as a mere decorative backdrop, engenders a more inclusive view of the society of the time.

From time to time unexpected things happen. Sometimes they make news. Even if they do, they can go by unnoticed and are often forgotten. On rare occasions, however, they break new ground and serve to bring issues to the surface that lay hidden forever behind the opaque and deceiving façade of normality. When this happens, the world is encouraged to change. The recent killing in Minneapolis of George Floyd while in police custody is one such event. The tragedy stirred the world but, more importantly, it brought to the fore the insidious racism that runs through every aspect of our lives – whether social, economic or political. None of us is untouched by it, as can be witnessed by the attention received by the incident on social media and the global reaction to it.

There is no period of history that has not been influenced by the migration of peoples and ideas, and no society that has not evolved as a result of it. In spite of this, African migrants in Malta today struggle to be treated as an integral part of our national community, and can be perceived as a faceless mass of anonymous people with no life stories and no names – a mere exotic feature in the concrete landscape. They hang and hop off the backs of garbage trucks, walk alone or in pairs on the edge of major motorways, or stream solemnly out of building sites at sundown, dusty and scruffy and adjusting their backpack full with the day’s material necessities. Their plight goes by unnoticed.

Black lives matter, no matter what. The stories of innumerable black migrants who travelled across the world – of their own volition or not – and who contributed irreversibly to the economic and civic growth of the West, are only a small fragment of the distressing overlap of two destinies, one that continues to haunt us. Black presence in the urban landscape of Malta today, for example, is not unlike that of Paris during the 1860s, when Haussmann was building the boulevards and parks that were to change irrevocably the identity of the metropolis and when new suburbs were springing up all around the old city.

The comparison came to my mind when, last October, during a visit the National Gallery in London, I stumbled by chance upon a lecture that was being delivered on the presence of black people in the Parisian landscape of the Second Empire. The speaker, Denise Murrell, a Postdoctoral Research Scholar at Columbia University, was curator of an exhibition held at the Wallach Art Gallery, New York, called Posing Modernity,which closed in February 2019 before being transferred to the Musée d’Orsay In Paris. Her doctorate thesis, a painstaking study of African models depicted in Impressionist paintings had, as starting point, the black servant holding up a bouquet of flowers in Manet’s Olympia (1863). By scouring the notebooks of the painters themselves and studying a contemporary census of the city, she was able to uncover the composition of the community that had taken up residence in the new, bohemian suburb of Batignolles in Northern Paris and to locate the names and addresses of the black models who sat for the young, radical artists who were their neighbours. In this way, she was able to confirm that Laure, the young black woman in Olympia, is also the black model of La Négresse and the servant featuring in Enfants aux Tuileries, two other paintings by Manet of the same period.

Her thesis is illuminating. It shows how changing modes of representing the black female figure were instrumental in the evolution of modern art. The legacy of Édouard Manet’s Olympia, according to Murrell, is that it was a turning point from a traditional portrayal of the black figure as an exotic ‘other’ towards modernist depictions of black people as active participants in everyday life. For the first time ever, the attention of the viewers’ gaze, especially the male one, has shifted from Olympia’s white naked body as a symbol of women of this kind that, formerly confined to the edges of society, had usurped the limelight to regenerate the city in her own image. This time the focus is on the hitherto ignored figure of the black servant, who, rather than being perceived as a mere decorative backdrop, engenders a more inclusive view of the society of the time. This was ultimately the mission of the nascent ‘painting of modern life’, as Baudelaire described the avant-garde, with its predilection for ordinary everyday life staged in domestic interiors and during the outdoor activities of the new bourgeoisie: boating expeditions, déjeuners sur l’herbe, and picnics of all kinds, modern life in its entirety, without the desire to select and edit, or to discriminate for that matter.

In the light of this, Murrell’s most significant contribution is certainly the poorly explored interface between the avant-garde artists of nineteenth-century Paris and the post-abolition community of free black Parisians. Her book, entitled ‘Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet to Matisse and Beyond’ (the catalogue of the exhibition), which was voted one of the best art books of 2018 by the New York Times, goes on to trace the impact of Manet’s reconsideration and projection of the black model into the twentieth century and across the Atlantic, where Henri Matisse frequented Harlem jazz clubs and re-interpreted portraits of black dancers to transform them into icons of modern beauty. As the book review states: ‘these and other works by the artist are set in dialogue with the urbane “New Negro” portraiture style with which Harlem Renaissance artists including Charles Alston and Laura Wheeler Waring defied racial stereotypes. The book concludes with a look at how Manet’s and Matisse’s depictions influenced Romare Bearden and continue to reverberate in the work of such global contemporary artists as Faith Ringgold, Aimé Mpane, Maud Sulter, and Mickalene Thomas, who draw on art history to explore its multiple voices’.

Murrell’s suggestion that a history of modernism cannot be complete until it examines the vital role of the black female muse within it, is complemented with her most admirable and humane campaign to ensure that galleries change generic titles such as La Négresse to include the name of the sitter. In this way, the mask of anonymity that since the creation of the work has deprived underprivileged subjects of their true identity, has finally – over a century later – been lifted.