Smoke and Mirrors

100 years ago, a fresh wind blew through the art scene. A new world order challenged populations after the ‘Great War’, but also increased their desire to live. At the Kunsthaus Zürich, the exciting decade of the roaring 20s is examined in detail.

Classical Architecture 2, 1927

Body colour and airbrush on paper

mounted on card, 50.8 x 36 cm

Pictet Collection, Geneva

© The Xanti Schawinsky Estate

Do you have a weakness for the roaring 20s? Do you enjoy the chic little dresses and cheeky dances of the flappers? Do you have a passion for Bauhaus design and Dada? Then you’ll love the Smoke and Mirrors exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich. Open until 11 October 2020, it shows what was new and exciting a century ago. With around 300 exhibits, 80 artists are presented, focusing on developments in the major cities of Zürich, Berlin, Paris and Vienna. What was innovatively created back then often still has an impact today. For this reason, contemporary artists have also been invited to respond to the impulses from the roaring 20s with their own works. The subtitle of the show reads: From Josephine Baker to Thomas Ruff.

But first, one has to take a step back and look at the situation from which this explosion of lust for life resulted. The First World War (1914-1918) had escalated into the bloodiest conflict in living memory, a worldwide pandemic followed. Europe was marked by the destruction of imperialist structures and political instability. Moreover, people had experienced years of hunger, epidemics and destruction and found themselves in a new social reality. Young creative people responded and experimented with gender roles, they played with language and created urban visions. A generational conflict broke space and empowered all genres of art.

Takka-Takka dances, 1926

Oil on canvas, 141 x 103 cm

Private collection

© The Estate of Ernest Neuschul

Faster, higher, further

The 1920s were marked by acceleration, and in so doing promoted photography as a new art form. Artists like Man Ray or Lázló Moholy-Nagy tried their hand at the emerging (black and white) medium, while Erwin Blumenfeld and Hannah Höch used photographic snippets for their provocative collages. A zoom on Höch’s realistically painted picture Die Journalisten (1925) shows six deformed heads of reporters. They were the highly regarded critical mediators of the zeitgeist. They explained to their readers, in the popular reportage style, what was going on. But why are the body parts deformed? Perhaps they were war-disabled, perhaps the artist wanted to allude to the Cubist painting of a Picasso.

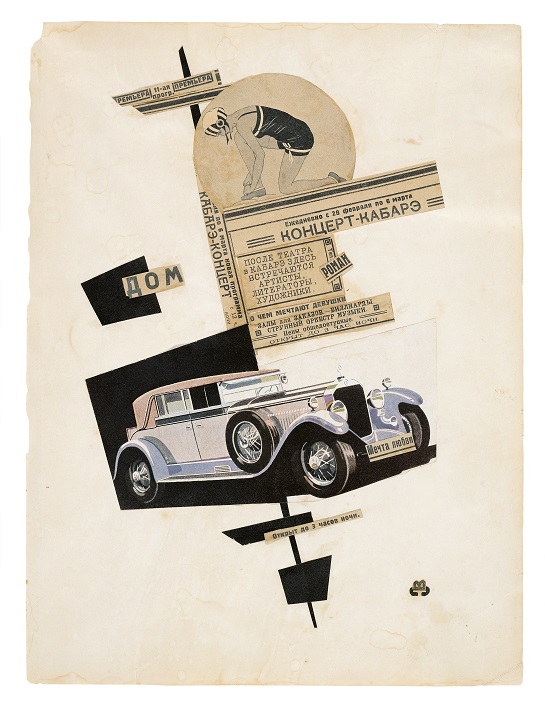

Untitled, 1929/1930

Collage (newspaper) on paper,

31.8 x 23.8 cm

Private collection, Zurich

© 2020 ProLitteris, Zurich

Exemplary for the liberated body feeling, especially of women, the exhibition shows a large number of original dresses. Here the makers benefit from the fact that Zürich has had a long tradition as a silk city and that valuable items on loan are available. The body-enhancing fashion, which includes wide ‘Marlene trousers’ and the ‘little black dress’ by Coco Chanel, conquered the dance halls in no time. To songs like You Look like a Man, my Darling, which described a woman in a ladies’ tuxedo, the young people enjoyed themselves in the clubs and jazz venues.

On the theatre stages, the same image prevailed. Not only in musical revues did the skirt hems become shorter, but modern expressive dance also shed the stiff ballet tutu. Half-naked women’s bodies had previously only been seen in private, but now they were jumping around barefoot in flowing robes to the delight of the astonished audience. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example, captured the sexually charged mood, partly fuelled by drug consumption, in drawings. Paul Klee, Xanti Schawinsky and Oskar Schlemmer captured the movements in abstract constructivist pictures.

Design classics

All this was only made possible by the rationalisation of the working environment, especially the introduction of assembly line work. This gave people more leisure time – they became consumers, so that film could establish itself as a cultural product. The ‘new living’ in the functional, light-flooded housing estates, equipped with their own bathrooms and fitted kitchens, became the new standard. The bright rooms were furnished with light-footed tubular steel furniture, design classics by Marcel Breuer, Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe, which we still appreciate today. Of course, the Bauhaus School in Dessau must be brought into play, this interdisciplinary think tank that has already made history with its own building architecture. The advertising poster art of the time, which reflects the new viewing habits, served the artists as an extended arm into everyday life.

The exhibition curators have made an effort to give female artists the voice they deserve as a matter of course. In this way, one can enjoy new perspectives on a decade that has been portrayed many times before. The different styles existing in parallel are not presented chronologically, but according to socio-cultural themes, which makes the tour entertaining. The question remains: are we currently experiencing déjà-vu as a result of the global economic crisis, the politically heated situation and social upheavals? Curator Cathérine Hug warns against jumping to conclusions. After all, history has always lived on inevitably in every present, she says. Instead, the exhibition aims to broaden the view and bring to the fore those phenomena of the 1920s that had a lasting aesthetic influence on society throughout Europe.

www.kunsthaus.ch