Public Sculpture

Should They Stay or Should They Go?

When people are angry about a malaise like racism it is almost to be expected that statues of controversial figures like Leopold II of Belgium, notorious for the atrocities against the Congolese in the 19th century, should become targets on which irate demonstrators verging into mobs should vent their frustrations.

The Brutal murder of George Floyd unleashed this backlash everywhere, with demonstrations being held internationally. The focus then shifted to monuments to statesmen like Churchill, Baden Powell and Clive who were perceived to have any racist stain on their character. When you stop to think that George Washington owned slaves one is at a loss to explain when to stop.

Which public monuments can also be deemed to be works of art? And, should, calamitously, Queen Victoria be removed, what would we replace her with? Another man in a suit? There are far too many already.

The world has always been a cruel place. Much as we artists try to create a world of beauty to uplift us out of our human bondage to greed and lust, it is very difficult to escape the fact that it is a dog-eat-dog world and minorities will sadly always be preyed upon and racism will continue unabated. Such is the way we are.

In sunny, happy Malta our connection with overt slavery ended with Napoleon who freed all the Barbary slaves that the Maltese corsairs dealt with as a regular above-board business in their raids all over the Mediterranean. Indeed by all accounts it was a lucrative trade; the first Count Preziosi created the lovely Villa Preziosi (Francia) in Lija on the proceeds of his astronomical profits in the slave trade.

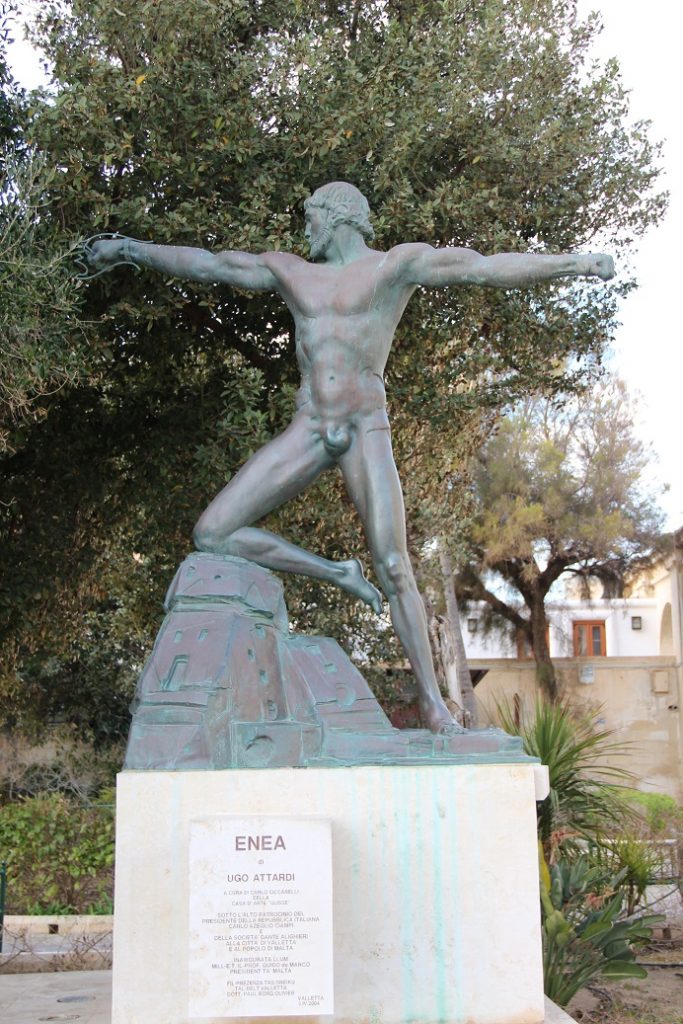

Ugo Attardi’s Aeneas hidden away in the Lower Barrakka Gardens, Valletta

Not to be left out of the latest trend, there is now a public outcry in Malta to remove Queen Victoria from her time-honoured place in front of the Biblioteca where she has presided over our lives, singularly unamused, since 1891 when the Valenti masterpiece wearing Maltese lace was placed – paid for by public subscription on the occasion of the Queen’s golden jubilee. The ostensible reason as to why people now want the Widow of Windsor removed is that she symbolises colonialism, which is utter rubbish, as from the time when Dido ruled Carthage to 1964 Malta was always part of something else – usually Sicily from the Roman period till 1530, the Knights of St John till 1798 and after the two year Blockade, Great Britain.

Therefore, using the colonial excuse to get rid of a work of art does set a horrendously dangerous precedent, which if left unchecked may leave us with possibly just Ħagar Qim!

But this is not the main reason for this essay.

Which public monuments can also be deemed to be works of art? And, should, calamitously, Queen Victoria be removed, what would we replace her with? Another man in a suit? There are far too many already.

There are, in Valletta – besides the wonderful Sciortino works on Great Siege Square and in the garden in front of the Phoenicia – the magnificent Neptune in the Palace Courtyard, the half-hidden monuments to Dante and grandmaster Vilhena and the totally hidden Attardi Aeneas in the Lower Barrakka. The statue of Sir Paul Boffa has artistic merit, but as we progress down the line we reach the level of competence without genius. There are the two composite monuments to events; Sette Giugnio and the execution of Dun Mikiel Scerri that are not exactly comparable to the Farnese bull but will just about do.

Our sculptors had not moved with the times – Henry Moore, Louise Bourgeois, Igor Mitoraj, to mention just three, remained unknown in Malta. When Austin Camilleri placed his Żieme in front of the Piano parliament it was soon removed for reasons unknown. We need to break this mould.

We don’t have to look far to gape at the stunning beauty of a Mitoraj sculpture. Just across the sea is Agrigento and juxtaposed against the marvellous Greek temples are a number of Mitoraj bronzes that look so amazingly right.

The beauty of the human figure as caught by the great Greek and Roman sculptors of antiquity was revived again during the Renaissance when the popes went back to Rome after their little holiday in Avignon, dragged back kicking and screaming by the intrepid Caterina Benincasa – also known as St Catherine of Siena – to start off a building frenzy that would have put Ramses the Great to shame. The popes and cardinals had no compunction about appropriating marbles from Ancient Rome and decorated their palaces with wonderful statuary; amazing discoveries like the Farnese Hercules, the Apollo of the Belvedere and the Laocoon would influence sculptors for centuries.

In Malta our statuary was mostly religious as the Order was more Catholic than the popes and the cardinals and were untainted by the excesses of the Borgia, Medici, Borghese, Barberini and Della Rovere clans, which were so extreme as to spark off the Reformation. Anyway, during the Renaissance the Order was too busy crossing swords with the Turks to think of something as frivolous as monumental statuary. They only started thinking of it when the grandmasters had an ongoing competition as to which of them would leave the greatest and most lasting memento of himself in St Johns Co Cathedral, the then Conventual Church.

Look to Rome, which was totally transformed by Lorenzo Bernini, who was sacrilegiously to melt the bronze on the dome of the Pantheon for Urban VIII to create the Baldachin in St Peters. Still today, art historians harangue the pope by quoting “quod non fecerunt barbari fecerunt Barberini”. Mind you, when you see the stunningly theatrical colonnade and the fountains of Piazza Navona I think you could forgive both Urban and Bernini.

Therefore, controversy over public monuments has always existed because no living person is universally admired or universally hated. There are no absolutes where real historical figures are concerned, and somewhere in Slovenia a statue of Julius Caesar was vandalised too! God knows why! I remember the time when the Nerik Mizzi bust on St John’s Square kept disappearing – it became a national joke.

Therefore, we have to be so careful about the way we place our monuments and statues and –in the same way that the Maltese paid an Italian sculptor to carve out Queen Victoria with such felicitous artistic results – we should open competition for this internationally as I simply cannot see one more politician in a suit popping up when you least expect it without getting the heebie-jeebies. Maybe they could wear a Roman toga instead…