Humanity’s Design and Demeanour

Ai Weiwei makes sense of what we make

One room, forty-two works, thirty years of widespread urban development addressed through a series of mammoth exhibits. Ai Weiwei enters the Design Museum’s ground floor exhibition space with concise yet unrelenting impact, his power of artistic advocacy for the first time positioning ‘design’ as its bullseye – albeit without explicitly defining the remit of what ‘design’ means to the mind of the activist artist.

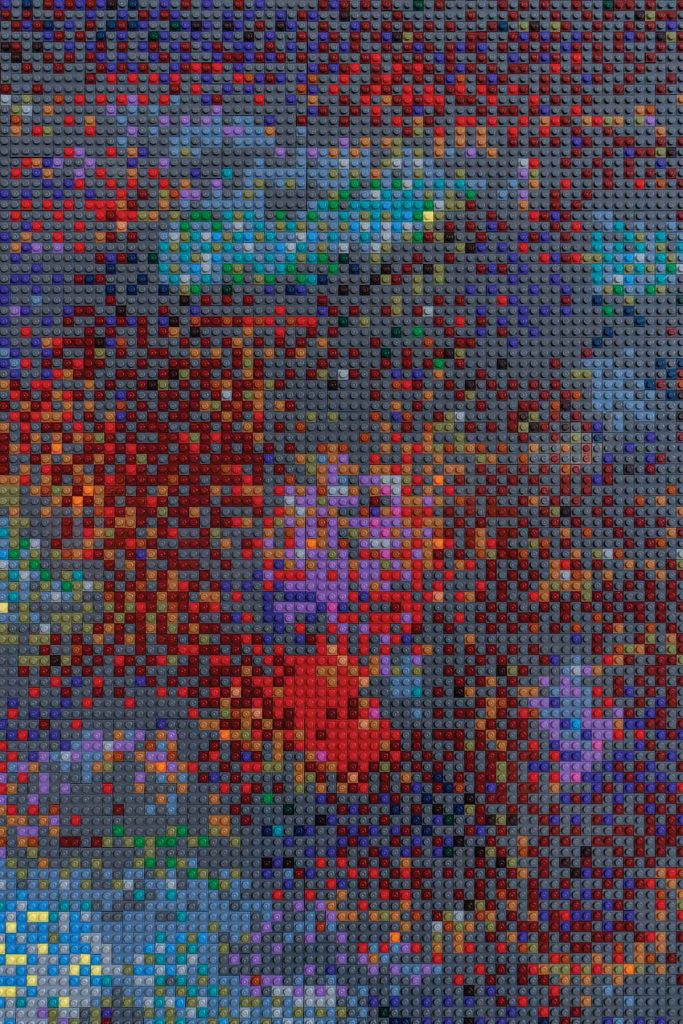

It seems it means everything. From Neolithic fragments of tools and weaponry to Lego pieces, life vests, porcelain cannonballs, and thousands of abeyant teapot spouts. Ai Weiwei is liberal with how wide he casts his net over human beings’ moulding of the social, ethical, and material pathways of the world through design. The exhibition is touted in its promotion as including “brand new works exploring different forms of making through the ages”. And so it does. But that feels secondary to the comment Ai Weiwei is making on humanity’s self-ordained authority over the world’s resources, materials, and even people.

He divides this collection of works into three categories: ‘evidence’, ‘construction/destruction’, and ‘ordinary things’. Respectively, the categories demonstrate a methodology of fragment gathering, a recording of inflicted ruin, and conversion of accepted meaning or use into something else. All categories do subscribe to the testimony of the artist’s use of “design and the history of making as a lens through which to consider what we value”. But the focus on ‘design’ somehow falls into the distance as the subject matter of each segment draws viewers in with a magnetism so characteristic of Ai’s oeuvre.

In the face of the individual works, it becomes challenging to remember what the show is about in its entirety. Each and every one of his copious compositions demands an explicit reckoning over the nuanced subject it addresses. This is not a curatorial failure per se, but the automatic effect that the potency many of Ai Weiwei’s works have on their viewer. For example, the ink and paper series titled Nian Nian Souvenir is devastating as an exposé of the 5,197 schoolchildren who died in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, rendering its viewer less concerned with the way its hand-carved jade seal has been designed to yield repeated symbols, and fully consumed with the message of volume vis-à-vis the event’s fatalities.

Design, therefore, often feels like a distant – or even mildly immaterial – framing point as the works are navigated across the large room. Subjects of exploitation, material gluttony and waste usurp attention. In Bejing 2003, a 150-hour video piece that marks the way the city has irrevocably changed from 2003 to present day through the filming of every single narrow alley and street of Bejing, seems to only have one focus: unchecked urban corrosion. Design as a touchpoint, in this instance, feels evasive.

Design becomes more dominant in the show’s smaller pieces – its sculptures that re-frame hangers, handcuffs, sex toys, take-out paraphernalia, cosmetics and so on as vehicles of consumerism, convenience, censorship, and other human malaises. Here the works do draw attention back to how these objects are ‘made’, and by extension what their design engenders and enables in human behaviour.

Despite the oscillation between tenuous and evident in its relation to a declared theme of design, the exhibition movingly succeeds in ‘making sense’ of things. But there again, this is the signature of Ai Weiwei – his sophisticatedly brazen input has always succeeded in turning people’s ethical heads, whether by spectacle or by substance.

Perhaps the christening of design as a thread throughout the exhibition merely works to give it allegiance to the museum that hosts it. Either way, the reason behind why these works were brought together takes a backseat to the impressions they individually leave – impressions of shock, sadness, acknowledgement, and repentance. Ai Weiwei’s manner of making sense is more about the design of human fallibility than the design of the things they make. Although that might be the exact point, and if so, the artist’s multi-layered grasp on the power of art as a tool for didacticism rests unrivalled.