Memories of Future Design

During the final preparations for Malta’s participation in the London Design Biennale, we meet the team behind the concept and actualisation, to hear about their intention behind the design.

June 2023 heralds Malta’s first participation in the relatively new London Design Biennale, an international showcase of design-led innovation, contemporary creativity and research at Somerset House on the banks of the Thames. Arts Council Malta has invested considerably in exporting its creative industries in recent years, with a pavilion at the Venice Biennale since 2017 and several Maltese appearances at international architecture biennials.

I meet the team responsible for the Malta’s pavilion, just a few short weeks before the set-up of their installation; the Open Square collective is made up of four creative practitioners from different fields, fitting nicely with the Biennale’s theme of The Global Game: Remapping Collaborations.

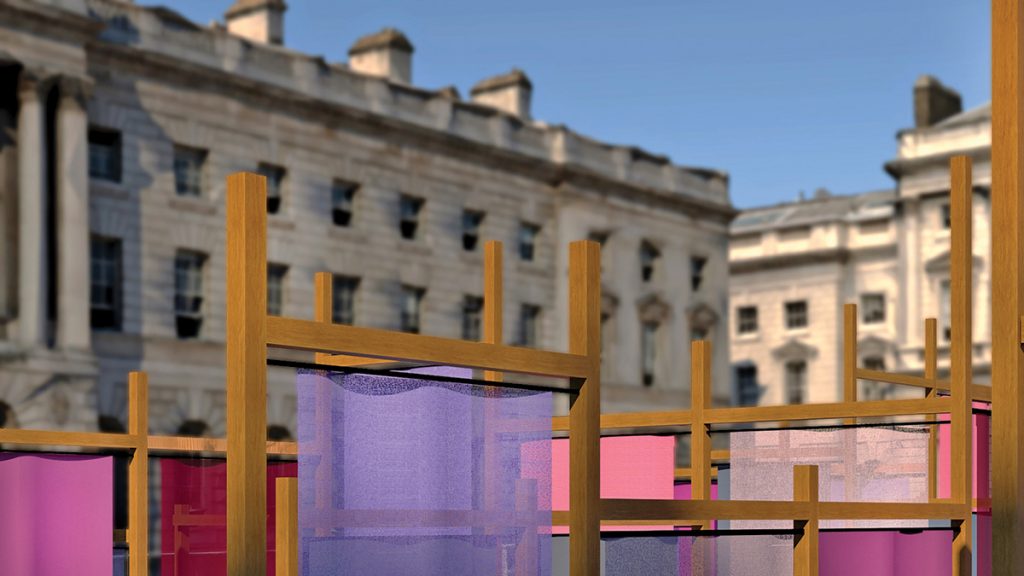

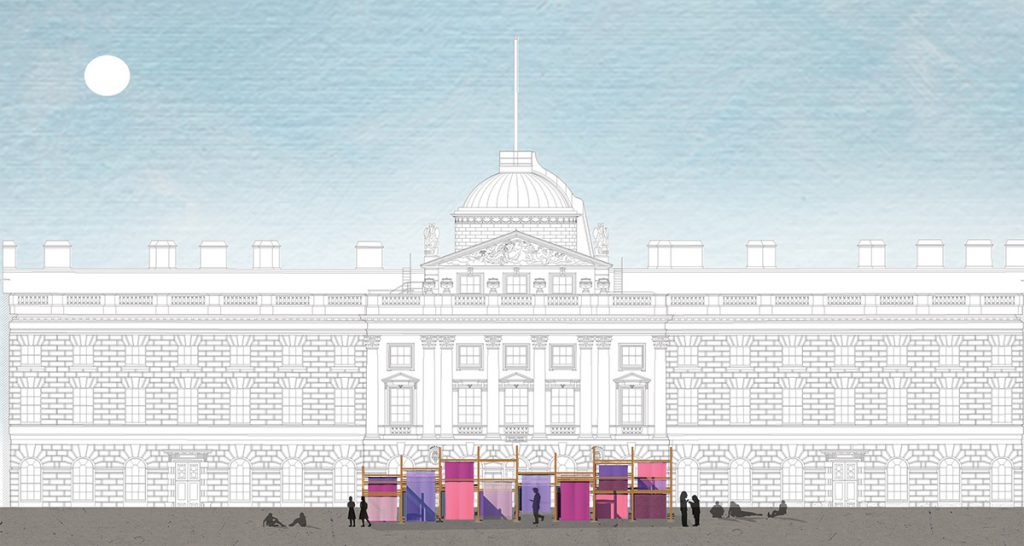

Their work, Urban Fabric, proposes a re -contextualisation of the traditional Maltese village core, combining elements of vernacular urban design with traditional fabric weaving and dyeing techniques. Wood, re-used stone and organic, sustainably-produced fabric take centre-stage in the installation which is at once structured but also soft and sail-like, placed within a large, formal Georgian square in the centre of London.

The team tells me how Open Square collective came together. Lead creative artist Matthew Joseph Casha and architect Alessia Deguara presented the element of spatial planning and an immersive space. Trevor Borg is an artist and academic, and an established figure in Malta’s contemporary art scene. It was important for the project to have an awareness of the environment, both in terms of the space around it, and in terms of its impact on the earth’s resources. And with couturier and designer Luke Azzopardi on board, the team of four was complete; he brought with him his interest in the specialised techniques of the ancient Phoenicians who for millennia lived, produced and traded in the Mediterranean. The team were inspired by the Phoenicians’ weaving and dyeing techniques in particular, as well as the ingenuity of their use of resources. This ethos; careful attention to detail and an awareness of the fragility of our ecosystems is present throughout the project – in how its materials are sourced and treated, and the plans for their re-use once the project has finished.

Ultimately, the team has produced a design that is both minimalist and luxurious; where raw materiality takes centre stage, but where design is refined and subtle. The structure’s materials speak with their own voice – materials are left natural and almost untreated; nothing is disguised or hidden. As we speak, it becomes apparent how important a genuine respect for the integrity of the materials is to the team, and consequently, the treatment of these materials. The integral nature of the design is understated, and yet behind it was an ambitious undertaking, with untreated wood, meticulous dyeing processes, and materials that can be disassembled & reused, including working with wood sections left at a length that is still acceptable for re-use after this project’s life-span.

The artists tell me they were aiming for the evocation of a sense of memory as well as space within the installation, and indeed their concept seems to draw diverse periods of history and memories together; the Phoenician era, much later centuries when Maltese villages began to mushroom around the island, the Georgian period in Britain, and contemporary times during this century flow around each other through the fluid streets of the installation.

And during its time in the square, the installation will create its own histories and narratives; natural colours may fade, timbers may shift, and fabrics may billow and float – this is part of the life-cycle of the natural materials it contains. Visitors will wander through it and create their own experiences, which will change with the weather and time of day. It is this cyclical, temporal quality that is intrinsic to natural materials and processes that the Urban Fabric project is quietly advocating for.

The village core from which the project takes its inspiration is not immediately recognisable in the project’s design. But its conceptualisation is present in its seemingly haphazard layout and its narrow, limestone streets, radiating from the focal-point of the village square and evolving over centuries. What were once thick, immoveable, yellow ochre walls have been transformed into almost its visual opposite; rich purples, vibrating on floating vertical fabrics, on a light and permeable frame. The only trace of the vernacular urban planning of the Mediterranean is its maze-like layout which gently leads the visitor along its streets and towards its centre.

Take a step back, and the contrast with the surrounding environment becomes clear. The Georgian square of Somerset House, itself steeped in British cultural history and characterised by symmetry, balance and proportion has become home to a fluid, almost breathing structure. But there exist other contrasts in this design exercise; a battle of architectures, and a subversion of hierarchies. The vernacular architecture of southern Europe, with its connotations of sun-soaked walls and Mediterranean living has shifted northwards. Its fluid and floating aesthetic and its temporality contrast with the solid walls which surround it, and their grandiosity and permanence. It inserts a chink – of light, of air, of mutability – that may come to represent something more in future times. The design contains a subversive element – whether intended or not – sneaking a village ‘pjazza’ into a square of palatial grandeur: interrupting its symmetry and poise with irregular pathways and billowing sails. This decolonial act lends importance to vernacular and organic urban planning, and places it on a world stage.

The installation proposes a collaboration with its surroundings, with the architecture around it, with the sprawling city of London and with the visitors who walk through it. But it also offers a conversation with the natural elements that it will face; the wind that will buffet it sails, the sun that will lighten its colours, and the rain that will, no doubt, soak it quite thoroughly. It lays down a challenge too, to the ugly concrete structures that have mushroomed in Malta over the past decades, all but obliterating its more dignified indigenous architecture.

We also talk about the technology that is employed in the piece; the heat-mapping tools that will reflect visitors’ movement within the space – that ebb and flow of people that any public space experiences as the day progresses. As in a village square, visitors may pass by slowly or quickly, may spend hours lingering, or may arrange to meet friends alongside it. Their movements will change the character of the space, and the light and colour within it.

Ultimately, good design is thoughtful, intuitive and sensitive; if it has a point to make, it doesn’t force that point home. This project has been conceived with a quiet certainty, one that allows it a feeling of fluidity and intimacy within an environment of grandeur.

The fourth edition of the London Design Biennale takes place from 1 to 25 June 2023 at Somerset House, London. The Malta Pavilion “Urban Fabric” by Open Square Collective, is commissioned by Arts Council Malta under the auspices of Malta’s Ministry for the National Heritage, the Arts and Local Government.

Open Square Collective, is an art and design collective by creative lead Matthew Joseph Casha, fashion designer Luke Azzopardi, artist Trevor Borg, and architect Alessia Deguara, supported by Ramona Depares and Gilbert Micallef.

Internationalisation Executive at Arts Council Malta, Dr Romina Delia, is project-leading Malta’s participation at the London Design Biennale 2023.