Fragments from a Collection

Dennis Vella was one of the leading promoters of young and budding artists, encouraging them to study, to take their art seriously and boldly.

Few are the people active in the Maltese art scene who are not familiar with the name of the late Dennis Vella. Of course, those who knew him personally, who were touched by his personality, intellect, and passion for art, have no difficulty in asserting his legacy to the Maltese modern and contemporary art world. You would hear several of his closest friends, acquaintances and colleagues describe him as a ‘pillar of art’, in admiration of his significant contribution to modern and contemporary art in Malta, arguably at a time when there was no one on the Island who was as knowledgeable in the field as he. Yet, it was his personality, rather than simply his commitment to art, that would colour the memories of those who knew him most intimately.

The majority of us – myself included – do not have such a privilege. At best, we may be introduced to the man, his life and philosophy, from a distance – that is, mostly through books, articles, a mention in some conversation, and especially through his own personal archive and collection. Indeed, the latter is the surest way for discovering untold facets of the man, perhaps hidden and unknown even by those closest to him.

Dennis Vella’s commitment to the twentieth-century Maltese art scene extended well beyond his role as art historian, lecturer, art critic or as curator of modern and contemporary art at the then National Museum of Fine Arts. Like some Maltese equivalent to the highly influential British art historian and museum director, Baron Kenneth Clark, within limits of course, Vella was one of the leading promoters of young and budding artists, encouraging them to study, to take their art seriously and boldly. Importantly, he would listen to them; he would travel, work, and invest extensively in them, as well as in international artists, gradually building his own large private collection of works of art.

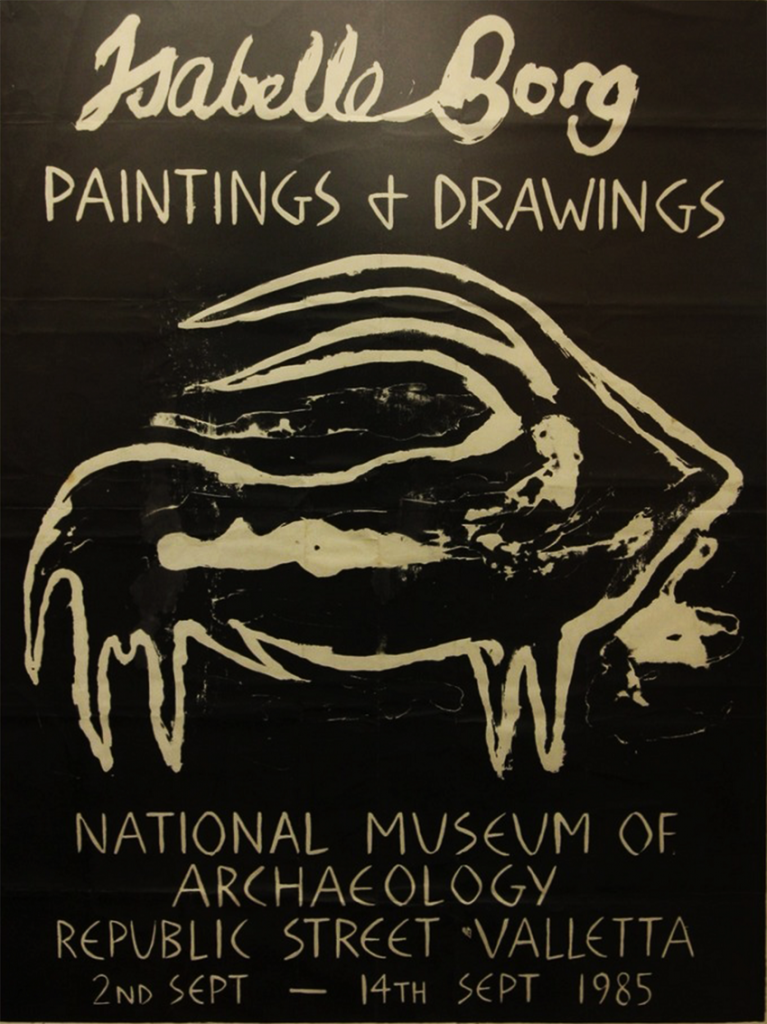

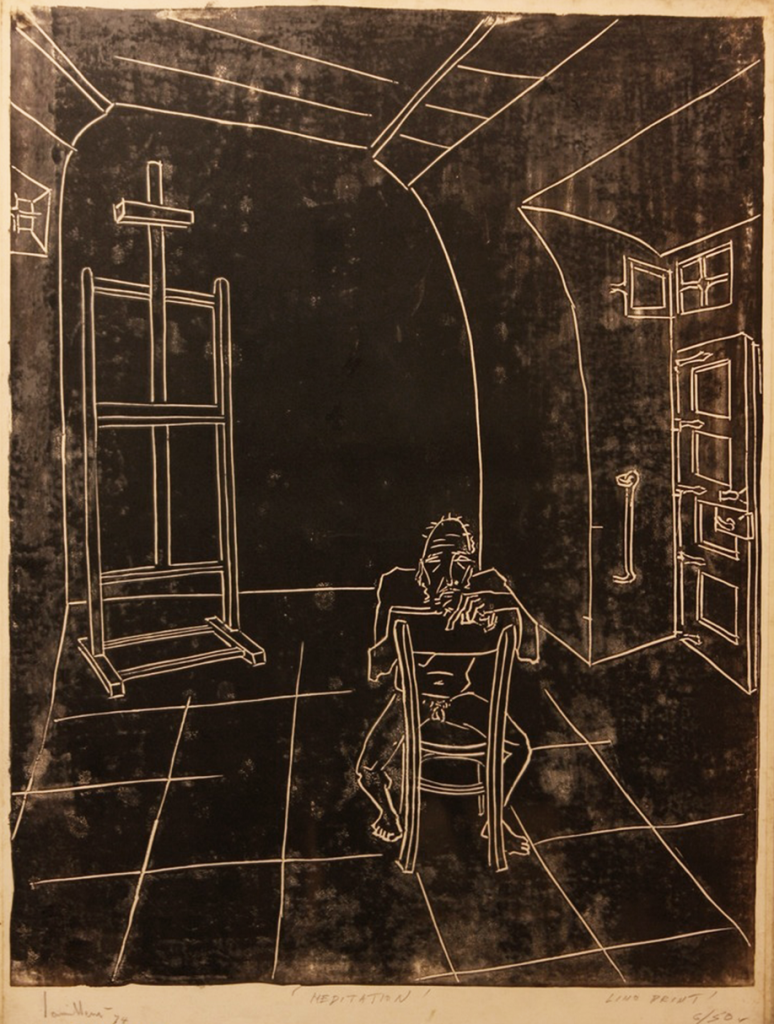

Private collections carry with them a particularly indispensable value. Walter Benjamin writes extensively about this particularly in an article called ‘Unpacking my Library’ published in his collection of essays, Illuminations. Here he describes ownership as “the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects.” It is this intimacy, the conscious choices of the owner, that reveals something further about the person. Vella chose to invest, especially, in Maltese modern art and that which was contemporary to his time. A recent Antiques and Fine Arts auction held at Obelisk Auction House in Attard, comprising of forty-five artworks from his private collection, clearly reveals this. Listed in the auction catalogue were, for example, works by Antoine Camilleri, Emvin Cremona, Norbert and Caesar Attard, Isabelle Borg, Neville Ferry, Paul Carbonaro, Giuseppe Arcidiacono, Clifford Arpa, and several others, including internationally-renowned artists such as Whistler, Paul Klee and Henri Matisse. Admittedly, it is, perhaps, only on rare occasions that the truly ‘great masterpieces’ – defined as such by an impersonal and somewhat disembodied art world – will appear in auction sales. When they do, however, their sales reach incomprehensible sums, and naturally, like some eclipse of absurdity, stunts the listening world. Suffice to recall that jaw-dropping moment when the counter ticked over 450 million dollars during the historic Christie’s sale of da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi; each red digit slashed and cut a little deeper into my ignorance of the contemporary art market.

For Vella, collecting art was not some indulgent undertaking. What led him to invest in art was not the vision of some auction house and those red-digit counters, increasing with every raised hand; but rather his vision of the deeper value of an art collection – as a means to connect with artists, to encourage them and propel them onwards. Collecting art is a way of entering a silent conversation of sorts with artists, irrelevant to time, space, culture, or even language. And that conversation is highly intimate, for its meaning is tightly wrapped up in the exchange between the collector and the artwork, with or without the presence of the artist.

Considering the current sway of things – ephemeral and mostly short-lived – collecting could easily come across as a largely counter-cultural act. Although not synonymous with the act of “preserving”, at least from a conservator’s point of view, to collect, nonetheless, keeps the desired object from being lost and funnelled down the untamed, uncertain, and collective stream of history, ironically enough. “Every passion borders on the chaotic,” Benjamin tells us, “but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories”. Thus, in collecting, the object is fished out from this great ocean of ‘chaos’, consciously chosen for uncontested personal reasons, and loved or given to be loved and remembered. What is judged beautiful and of value, or what is considered priceless by the prevailing age, does not apply. To the owner, all sorts of criteria are revised because the object’s value ceases to be an apparent (or numerical) one; condition matters less, especially once the object forms part of the collection. The permanence of the object – and by extension, of the collection – is in that it cannot be replaced or forgotten as it is itself a vessel of memory in which, to some literal extent, the owner invests some part of his or her life, and passion, in. It is perhaps, what Walter Benjamin meant when he wrote that it is “not that they [the collected objects] come alive in him; it is he who lives in them”, and for the same reason, why “the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner”.

Here, we step into difficult territory. For how is a collection meant to live on once the owner passes away, without it becoming a shrine of sorts, maintained by those who are not yet able to let go? The passionate flame that once built the collection in the first place is spent. It no longer burns, if not similarly in other hearts. Passion does indeed play an important part in all of this. For the same reasons that artists keep creating, collectors keep collecting till the day they are forced to stop, which is a death of its own kind anyway. One can say that a man like Dennis Vella died at least two deaths – the day he stopped collecting, and the day cancer had its final say. A decade on since his passing, his once private collection is now being passed on to the public. And with the object itself, his views, investments, connections, values, his loves, his passion, also live and are passed on – no longer as something concentrated in one personal collection, but as fragments which will hopefully serve to build several others.