At the Crack of Dawn

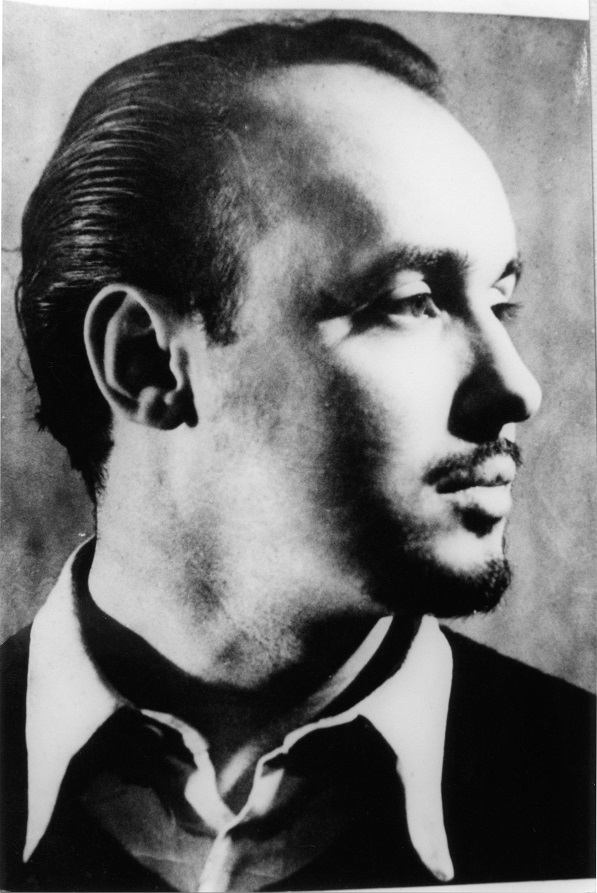

One hundred years since Emvin Cremona’s birth, Giulia Privatelli looks back on the life, work and legacy of a ground-breaking Maltese artist.

“Art is eternal, but it cannot be immortal, it may live for a year or for millennia, but the time of its material destruction will always come: it will remain eternal as gesture, but it will die as material.”

Lucio Fontana, Spatial Manifesto, 1947

Time has a way of crystallising what is beyond matter; ironically enough, to us mortals it seems to inject meaning into what truly matters. One of our rebellious human responses to time – to preserve that which matters – is to memorialise, to make monuments out of moments and immortals out of mortals, to fix a name or an image on paper, canvas, clay, metal, marble or stone… on some kind of material which is, ultimately, perishable. In our attempt to defy time – which is beyond matter – the deeper we seem to bury ourselves in matter, and the deeper are the signs we leave in that matter. And we do so ceaselessly, endlessly, as if that very same gesture would, as Lucio Fontana puts it, “remain eternal”. While Fontana slashed into his canvases, our very own Emvin Cremona – in what is perhaps the most brutally honest climax of his artistic career – smashed planes of glass on thick impasto – a grave of thick earth, one could imagine, that buries us in a material culture from which we desire to break free.

Emmanuel Vincent Cremona, later shortened to Emvin, was born in 1919. A hundred years ago, several Maltese citizens stood together in one of the most consequential revolts in Maltese history. In Argentina, many rioted (and fell) together in what was later mummified as the Tragic Week of Buenos Aires; in Russia, a civil war raged and hurtled towards an end; the Third Anglo-Afghan War commenced, while the First World War was signed off with the Treaty of Versailles and of Saint-Germain; modern-day Turkey was born with the Turkish War of Independence, with Estonia and Latvia quickly following suit; Adolf Hitler gave his first speech on behalf of the German Worker’s Party, and Benito Mussolini founded his Fascist political movement; Walter Gropius issued the Bauhaus Manifesto, as the Eddington experiment shed new light in the field of stars. All was done in the name of progress – politically, economically, and culturally. Emvin Cremona (and with him, Esprit Barthet), was born into a sprouting world that had finally started to emerge from the cracks of an ageing and broken seed; in that sapling he was to leave a lasting impression – one that may still be recognised to this day.

“Only a fool will build in defiance of the past,” writes Béla Bartók. “What is new and significant must be grafted onto old roots, the truly vital roots that are chosen with great care from the ones that merely survive”. In twentieth-century Malta, there was no shortage of old roots to cling to. The real difficulty was to know which ones to let go of, and when. It was perhaps somewhat easier for an artist like Willie Apap (1918–1970), who chose to distance and eventually detach himself from Malta, to loosen his grip on such ‘old roots’, albeit still not being able to abandon them completely. Cremona, like most of his peers, received his first artistic academic training at the Malta Government School of Art under the imposing and conservative influence of Master of Painting Edward Caruana Dingli (1876–1950). It was, perhaps, the refreshing outlook of his other tutor, the Master of Modern Etching, Carmenu Mangion (1905–1997), that instilled within Cremona a certain predisposition and sensibility for the art of design, and which was reinforced further through his contact with contemporary artistic circles in London and Paris during his years of study there. Sadly, these ties were quickly severed with the outbreak of the Second World War, when he was forced to return to Malta.

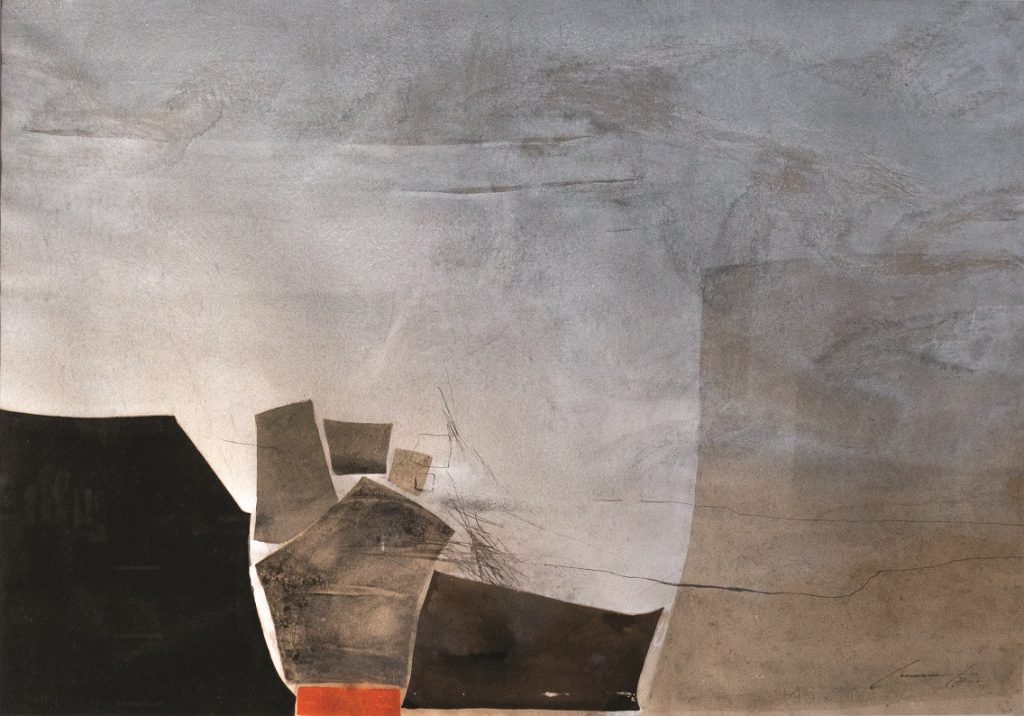

This lesion is also somewhat mirrored in Cremona’s artistic output, multifaceted as it was. Indeed, while his numerous public commissions – particularly his ecclesiastical works – dutifully sung colourful and stylised praises, his private works softly whispered the radical artistic desires of his heart; a ‘double vocabulary’ as Professor Henry Frendo calls it. Here was an artist who, with one hand, could reach out to those ‘truly vital roots’ and build upon them, as social responsibilities and economic pressures also forced him to tighten his grip on wilting ‘old roots’. “I cannot understand Cremona’s magnificent Broken Glass series, when I am confronted with his series of St Paul throughout the churches of the Maltese Islands: neither can I understand this avant-garde Broken Glass series juxtaposed with his artistic and political allegiance to the feudal-anachronistic massive politics of the Catholic Church in the 1960s,” laments Professor Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci. Cremona’s dual artistic output and, quite literally, his inability to completely shatter and pierce through the density of tradition, thus liberating himself from it, is ultimately at the root of this frustrated but well-meaning plea.

Yet, it is precisely this duality that makes Cremona a truly relatable artist; one whose artistic identity swung precariously back and forth between the traditional and the experimental, between security and defiance. While Malta’s heritage provided Cremona with the cultural backdrop for his figurative and decorative works, and, to some extent, even to his abstractions, it was his personal restlessness and bubbling desire to fracture the constraints of tradition that led him to create such outstanding and daring abstract works. His reaction, his own personal rebellion, cracked the misleadingly fragile-looking glass. As it so happens, that honest, incomplete crack, like Lucio Fontana’s gash, is what ‘immortalised’ his art. His gesture; immortal enough, at least, for us to still speak of Emvin Cremona and his art, a century on from his birth.