The Nature of Architecture

I sometimes wonder whether I obey some ancestral impulse when I am irresistibly drawn to these primitive constructions carved out of the landscape.

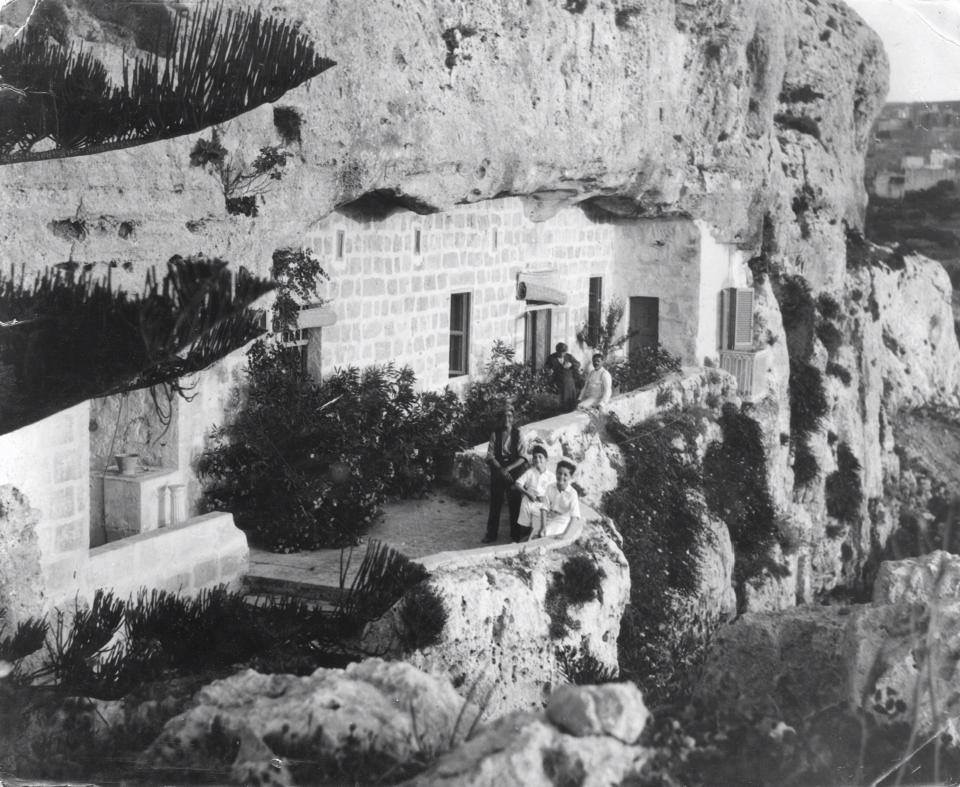

When my father was a small boy, he used to spend the hot summer months with his family in a ‘cool’ house that was perched on the sheer stone edge of the hill that dominated Ghadira Bay. The house, aptly called Ghar-u-casa (cave-and-a-home), was built on a natural rock platform at the foot of a millennial cave and consisted simply of a vernacular façade plugged onto the mouth that once overlooked the sandy beach below.

I have often imagined the arduous trip undertaken by the entire family, a karozzin as sole means of transport, that departed from the fortified harbour of Valletta in the early hours of the morning for the idyllic rural settlement of Mellieħa in the isolated northern end of the island; the excitement that filled my father and his younger brother to the point of exhaustion on their arrival at their summer abode, the warm air and the fading light at the end of the journey, the welcoming cool, frugal stone house surrounded by so much luscious nature: walls of prickly pear and a roof woven of vine leaves, all wrapped in the silky summer breeze that reached up from the sea below. Nature and architecture were inseparably intertwined in the shadows cast by the glow of the candles on that first night in the country, a tapestry, natural and man-made in equal measure, highlighted by fireflies darting in the sweet night air and silence descending on the hill.

Of troglodytic architecture, buildings partially or entirely hewn out of the rock, with the Hypogeum, Malta perhaps has the oldest and most unique example created by mankind. I sometimes wonder whether I obey some ancestral impulse when I am irresistibly drawn to these primitive constructions carved out of the landscape. Several years ago, Architecture Project (AP) was invited to participate in a competition for a temporary protective shelter for five churches in Lalibela, a town in the Amhara region of northern Ethiopia. The breath-taking rock-cut churches, dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, are pilgrimage sites for Coptic Christians. Carved out of the granitic rock of the hill itself, the subterranean monoliths include the huge Bete Medhane Alem, and Bete Giyorgis with its Greek cross plan. The churches are joined by tunnels and trenches and carved bas-reliefs and coloured frescoes decorate the inside walls. I spent a night vigil there during one of the big religious festivals that attract hundreds of white-robed pilgrims at sunset, crowding the courtyards of the churches, praying in the shade of the surrounding jacaranda trees and bearing witness to Christianity in its most unadulterated and powerful form.

An equally spiritual and awe-inspiring architectural revelation was reserved for me in Yerevan a month ago, when I was invited for the birthday party of a friend of mine. A ride in the country through the hilly Armenian landscape, with Mount Ararat as a permanent backdrop, took us to the monastery of Geghard at the entrance of the Upper Azat Valley. The monastery contains a number of churches and tombs, most of them cut from the living rock, a complex of mediaeval buildings set into a landscape of great natural beauty with high cliffs on the northern side of the enclave and a defensive wall encircling the rest.

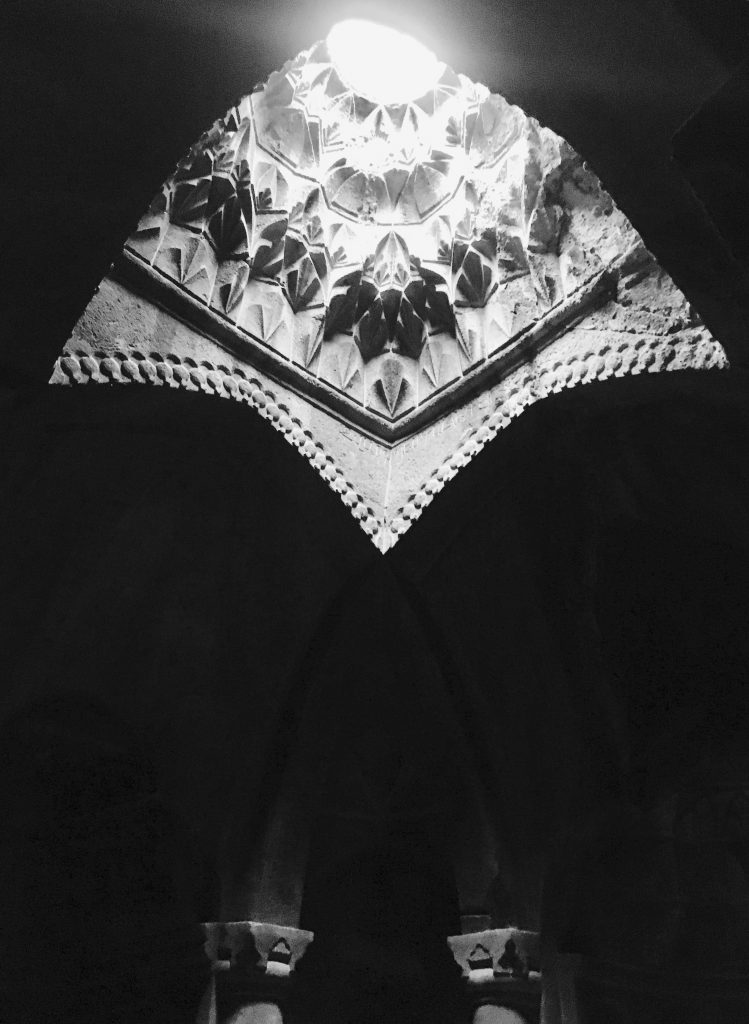

The monument evolved between the 4th and 13th centuries. According to tradition, the original monastery, known as Ayrivank or the Monastery-in-the-Cave, was founded by St Gregory the Illuminator, following the adoption of Christianity as the state religion in Armenia. The main architectural complex was completed in the 13th century and consists of the cathedral, the adjacent narthex, eastern and western rock-cut churches, the family tombs of the princes as well as various cells and numerous rock-cut cross-stones. The plan of the main church is a Greek cross covered with a dome on a square base and linked with the supporting columns by vaulting.

In this ancient, silent, mysterious architectural masterpiece of mediaeval Armenia where, in addition to the religious constructions, a school, scriptorium, library and many rock-cut cells used as dwellings for clergymen could be found, Armenian manuscript art was developed in the 13th century. This is characterised by an intricate and beautifully wrought composition of lines that echoes the stone carvings of these top-lit, domed chambers, highlighted by cascading light falling through the heavily sculpted oculi.

Is it this quality of zenithal light that produces the intense spiritual atmosphere of these structures – which seem as if they were created for eternity? In his essay Eupalinos ou L’Architecte (1921), Paul Valéry described the architect’s work as starting exactly where God left off. The collaboration of both is the prerequisite for a style of architecture that is timeless. The essay takes the form of a Platonic prose dialogue between the shades of Socrates and Phaedrus in Hades, as they debate the spiritual nature of Architecture. Valéry’s thesis is that Nature, the work of the Creator, is further developed by the architect to resist the destructive forces of chaos (durability) and to satisfy the needs of Man’s body (utility) as well as those of his soul (beauty).

The building project thus informs matter in a process similar to that of gnosis. In so doing, Architecture calls into play the hidden harmonies contained in Nature’s Lucidus Ordo, the unity and clarity generated by the organic laws of mathematics. At this moment of creation, when Nature and Architecture come to co-exist harmoniously, Valéry’s dialectics of opposites – past and present, accident and essence, ephemeral and lasting, proximity and distance, motion and rest, lightness and gravity – find an ideal equilibrium and the timeless building is born, like a piece of heaven created out of the imperfection of the earth.

AP’s project for shelters for five churches in Lalibela

The power of the intervention was derived from the uninterrupted connection between the monuments, the landscape, the crowds of pilgrims, the shelters themselves and the all-encompassing Faith that brought this sacred composition together. The project was conceived as a semi-translucent cloud floating above the religious site, preserving the continuity between the monument and the landscape out of which it was carved, and the landscape is untouched. The cloud creates a complementary secondary landscape belonging to the sky as well as to the millennia.