Of Myths and Men

“He is not necessarily beautiful in himself but is made beautiful by the projected desire of his admirers.”

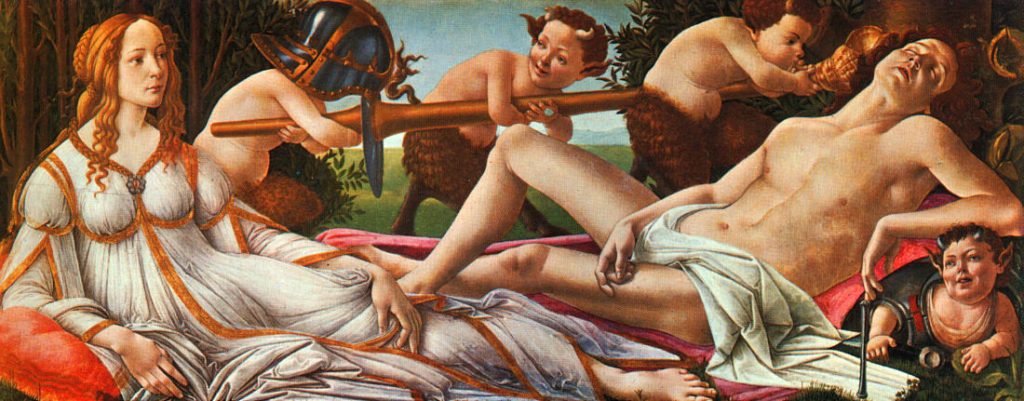

I owe my love of art to my mother. She loved detail above all and admired the ability of the Great Masters to imitate reality so closely. She took me on a visit to the National Gallery in London for the first time when I was eleven. I remember her explaining Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait, the depiction of a couple that had just been joined in marriage, showing me their fur-lined clothes and wealthy interior, and pointing to the artist’s reflection in the mirror on the back wall. Later, we stood in front of Botticelli’s Venus and Mars and I remember being strangely disturbed by it. In comparison, the Arnolfini portrait seemed so serene, but stiff, stuffy and settled. Venus and Mars, on the other hand, was my first taste of eroticism as well as my first lesson in love.

“That is Mars, the God of War, the man of action,” my mother explained. “He is resting after some very strenuous and life-threatening exploit. And that lady whose all-knowing gaze rests on the sleeping man is Venus, Goddess of Love. That is what love is, watching over someone, and understanding”.

Years later, as I began to read more about the Renaissance, and Botticelli’s painting in particular, I learned about the more mainstream, academic versions of the symbolism contained in the painting and the message it conveyed. Love will triumph over War. Also, sexual prowess is greater than the physical strength of a warrior.

Botticelli depicted Venus and Mars facing each other, accompanied by playful satyrs, symbols of sex or lust. You can sense these mythological creatures are up to some considerable mischief as they disturb the tranquillity of the mystical garden of myrtle trees – the evergreen with white flowers sacred to Venus – where the beautiful gods lie. Mars is depicted naked and locked in the deepest sleep. Even the sound of a satyr’s bellowing seashell horn cannot wake him. While he is lost to the world, Venus contemplates his unaffected beauty, and the satyrs use his weapons and armour to amuse themselves. One wears Mars’ helmet and, with his two companions, attempts to steal away with the warrior’s lance, while on the far lower right of the painting another is cheekily crawling through Mars’ breast-plate.

In contrast, Venus is clothed. She gazes at the sleeping God of War, satisfied somehow, confident and in control. Her flowing white, gold-trimmed gown is fastened with a pearl-encrusted brooch. Is this scene intended to depict the immediate aftermath of the couple’s lovemaking? The lance and the seashell are surely objects of sexual symbolism and the painting portrays an aura of carnal sensuality. Looking back on the hold that the painting had on me in those pre-pubescent years, I cannot but feel that its power had something to do with the contrast between Mars’ candid ingenuity, that, in spite of his belligerent reputation, is central to the painting, and Venus’ compassionate but discerning gaze.

Strangely, the subject of the innocent warrior or sinner re-emerged abundantly in the books I read during my sixth form years. Too many to mention, they included writers from Graham Greene to Francois Mauriac and Heinrich Boll. I suppose no actor incarnated better the role of the sinner-saint than Richard Gere in his rich filmography of the eighties which I devoured. American Gigolo is a trendy and unexpectedly poignant handling of this theme. Julian Kay, the gigolo of the title played by Gere, is vulnerable, and a little too ‘good’ for his own good. Like Venus watching over Mars in his fragile moment of slumber, the audience cannot but care for Julian. What he does for a living, making love to rich, elderly women, gives him the means to treat himself to the luxuries by which Beverly Hills measures success. He drives a Mercedes, owns an expensive wardrobe and rare collection of antique vases and is a member of exclusive country clubs.

Of course, this is Hollywood, and the protagonist is destined to fall in love with his client. At the same time, however, he is being framed for the murder of a Palm Springs socialite. The movie wants us to believe in the power of love to redeem both characters: Julian learns to love unselfishly, irrespective of money, and the woman learns to love honestly, clearly not a characteristic of the marriage to her influential politician husband.

This business of redemption works on the backdrop of an engaging story about murder, framing, and police investigations, but the whole movie has a deep sadness about it. Take away the story’s sensational aspects, Beverly Hill interiors and Armani suits, and what is left is a study in loneliness. Richard Gere’s performance is central to this, and some of his scenes, whether when he reads the morning paper, rearranges his paintings, exercises or selects his clothes for the day, underline the void that marks his life. American Gigolo leaves you with the curious feeling that even if women were paying this man to sleep with them, they genuinely cared about him and watched over him. They understood his covert shyness, his inability to expose his vulnerability, and they accepted his qualities of a loner that made it easier for him to love when it was just another deal.

Somehow, it strikes me how current this all is on the courtship battlefield today and how timeless is the message contained in Botticelli’s painting. Is a man’s chief vulnerability his reluctance or inability to show his vulnerability? Is sex a means to hide that weakness? And is the fairer sex, Venus in Botticelli’s painting, knowingly pandering to man’s artifice of deception?

Last year’s show by Marlene Dumas at David Zwirner’s gallery in New York entitled Myths and Mortals, seems to say so. The huge show, numbering 29 oils and 33 ink wash drawings was inspired by Shakespeare’s debut poem of 1593, Venus and Adonis, a Baroque exploration of a tale Ovid includes in Book X of his Metamorphoses. Dumas focuses on the erotic, specifically female love, and the mysterious coupling of male and female sensual and sexual sensibilities.

In Ovid, Cupid accidentally wounds Venus, his mother, with one of his arrows, and she falls madly in love with the beautiful hunter Adonis. Ovid is clear that Venus is a victim and her love is mad, a pathological condition that makes the immortal goddess love the all-too-mortal hunter. In his interpretation of the tale, Shakespeare endows Venus with an erotic frenzy where she wishes she were a man. Dumas transforms this gender inversion into a tender commentary on new male-female relations. The artist seems to want to conquer the traditional territory of male artists, the nude, in order to express contemporary male-female sensibilities.

Amends is a full-frontal male nude that we view over the shoulders of female spectators. His arms are spread and his palms face the audience as though to say that this is all there is, all that is on offer. He stares at us, empty of emotion and refusing to admit a multitude of other covert, submerged insecurities, fears and reasons to be loved. He is not necessarily beautiful in himself but is made beautiful by the projected desire of his admirers. It is as though Botticelli’s Mars, on waking up from his deep slumber, hides his fragility and disorientation behind the armour of his own nakedness and is happy to exist as a function of the reflection that Venus offers him. This was perhaps Richard Gere’s greatest contribution, way back in the eighties, to the expression of the emotional state of the contemporary male.