Caravaggio and the Charisma Machine.

Of late I have been thinking a lot about Caravaggio. I’m not sure exactly why. Although the link is extremely tenuous, I think that it has something to do with the U.S. elections and with Donald Trump in particular.

Truth be told, Caravaggio pops up a lot in my personal and professional life. He makes an appearance in various forms, surfacing in exhibitions, lectures and in projects I’m involved in that relate to his Maltese legacy. Clearly, he likes to be noticed and to be talked about. He is as controversial, and with an equal talent for showmanship, as Donald Trump, who, as we all have understood over the last few decades, loves attention too. As for Trump, one of the many ways in which this compulsion manifests itself is his insistence on making cameo appearances in movies and TV shows, where he always plays himself in his own properties. Caravaggio too, motivated perhaps by the same narcissistic intention, played himself when he painted his likeness over and over again. At times he’s the protagonist, Goliath or the sick Bacchus, at others, he’s just a weary witness, lurking in the shadows, as in the Martyrdom of St. Ursula.

Unfortunately, unlike little Kevin in Home Alone 2, who gets lost in New York, finds himself in the glitzy Plaza Hotel and asks the future President – who just happens to be hanging around – the way to the lobby, I never had the good fortune of bumping into Caravaggio and asking him directions. In spite of this, I often think of him walking the streets of Valletta – a rough but beautiful and charismatic man who loves the pleasures of life, wine and food and sex, and has the power to take what and who he likes. I imagine him pointing at the people he fancies, whatever their social class, people he wants to immortalise in his paintings and who could serve as models or become his lovers. He points, like his own Christ in the Calling of St. Matthew. I want YOU. And you and you. All these people will get into trouble, just like Christ’s disciples did before, not as a consequence of their own choices, but, rather, of his. I am sure that were I to come across Caravaggio one day in Republic Street, he would set his charisma machine in motion and I would, without any hesitation, become a follower. Donald Trump must be the same. I guess he, too, is used to getting whatever he wants.

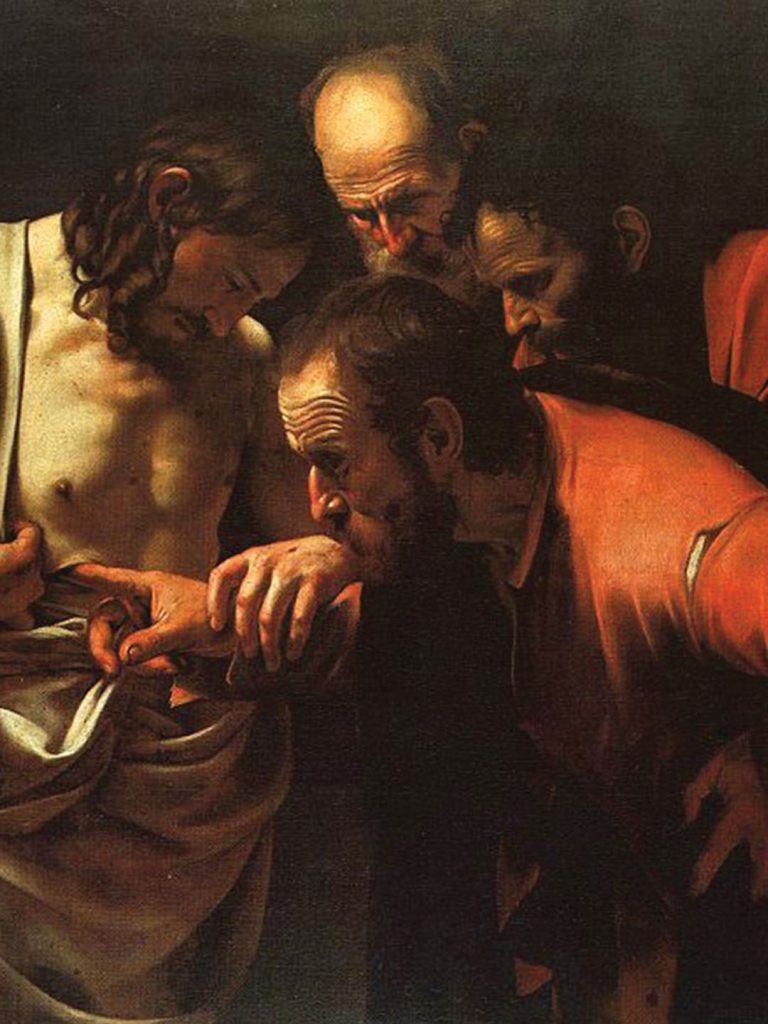

As the reader can deduce, although my hopes are rather dim that our paths will one day cross, the baroque enfant terrible and I, I speak about him a lot. Sometimes, as we emerge from a particularly poignant meeting and walk down the streets of Valletta, feeling tired and a bit forlorn, I console my colleagues by describing Caravaggio’s Incredulity of St Thomas, which, I explain, is a lesson on how to transform pain into the pleasure of feeling alive. Besides, to me, it is the best example I know of charisma at work.

The classic explanation of the painting is that it depicts the story of doubting Thomas who needs proof that Jesus has risen from the dead. My theory, instead, is that Caravaggio had no patience for Thomas, his hesitations and the weakness of his character. He was interested only in what Christ was feeling. What he is depicting here, I sense, was what he imagined was the incredulous pleasure that Christ must have experienced on feeling alive again after three dull days confined to the still and musty darkness of a rock-hewn tomb. In the painting, Jesus clearly wants contact, physical even, with the living. Still uncertain of the role he’s been given, he desperately needs evidence that this is for real. Thomas, flushed and foolish looking, places his finger in his wound. The pain Jesus feels, as he guides his disciple’s hand towards the sensitive spot, a dull pain as of an old scar, is a pleasurable one. It gives him a sense again of the life that’s running through his veins, as Robbie Williams describes the sensation two millennia later. And as his disciples gather around him and press closer, four furrowed heads crowding together in a vortex of wonder and amazement at this symbolic wound, a new life for the world is born and the sins and suffering of the mankind are redeemed.

In Catholic doctrine, the word ‘charisma’ was used to define the ‘gift of grace’ that a priest received to transcend his own human frailty and to allow the rituals he performs to acquire superior and spiritual meaning. In a secular society, it is applied to a forceful leader whose powers are a function of his feelings, his ability to express them and to attract the feelings of others. His actions are secondary to this. The charismatic leader has his finger on the pulse of his people. He has the gift of empathy and understands their suffering, exploiting their wounds and their weaknesses to give them hope in a superior existence.

One famous case of staged compassion by a charismatic leader springs to mind. In March 1799, during his Egyptian campaign, General Bonaparte paid a spectacular visit to his soldiers who were struck by the bubonic plague following the violent sack and capture of Jaffa. The plague had all but decimated the army and the survivors and the stricken took refuge in the Armenian Monastery of Saint Nicholas. It was said that Bonaparte touched and consoled the soldiers – a daring act of mercy considered to be both magniloquent and suicidal, although the means by which the plague spread were still unknown at the beginning of the 19th century. The scene was immortalised in a painting by Antoine-Jean Gros, commissioned in an attempt to embellish Bonaparte’s mythology, that was exhibited at the Salon de Paris between Napoleon’s proclamation as Emperor and his coronation at Notre-Dame de Paris, clearly a full turn of the wheel of the Charisma Machine. In the painting, Napoleon poses as a saviour of his people while an officer standing behind tries to stop him from touching the sores of an afflicted soldier. An oversized French flag flies above the walls of Jaffa that serve all around as a distant backdrop, while in the foreground the picture plane is crammed with prostrate and reclining bodies, a metaphor of the suffering of the French people.

The staged spectacle continues to this day. In Italy, Silvio Berlusconi hugs and consoles a desperate elderly lady who could be anyone’s grandmother. Her home has collapsed in the earthquake and all her belongings are dispersed together with, most bizarrely, her denture, over whose loss she moans and cries. Silvio soothes her and promises to buy her a new set of false teeth. She stops sobbing and is silent, comforted by his words. In Turkey, Erdogan instructs his chauffeur to stop his car as news reaches him that a young man is about to commit suicide by jumping off the bridge. He speaks to the wretched youth to understand his motives and promises to help him out of his dire predicament. In the States, Trump appears in TV shows and Hollywood movies and the problems of his people immediately pale in the distance and lose their serious cast.

Richard Sennett, in his marvellous book, The Fall of Public Man writes extensively about charisma. The charismatic leader will “bind and blind people as surely as a demonic figure if he can focus them upon his tastes, what his wife is wearing in public, his love of dogs. He will dine with an ordinary family, and arouse enormous interest among the public, the day after he enacts a law that devastates the workers of his country-and this action will pass unnoticed in the excitement about his dinner… What has grown out of the politics of personality is charisma as a force for stabilising ordinary political life. The charismatic leader is the agent through whom politics can enter on a smooth course, avoiding troublesome issues or divisive questions of ideology”. Charisma, in the hands of the wrong politician, can be a very dangerous machine.

Which brings me back to the U.S. elections. If Biden won, he did so on the strength of the votes of the Democrats, of the conservatives and the moderates, the admirers of Kamala Harris, of the black community, of those emotionally attached to former President Barak Obama, of the renegade Republicans, the floaters, the late deciders, the disillusioned former followers of Trump. Trump’s seventy-three million or so votes, on the other hand, were all earned by him and him alone, and were exclusively for him, thanks to the efficiency of his own personal charisma. He may have lost the elections, but the elections were exclusively about him.

Trouble is, self-marketing magicians are forever tempting fate and falling victim to self-fulfilling prophecies. Although there has been a plethora of theories about how Caravaggio died, from sunstroke or syphilis to assassination by the Knights of Malta, recent studies of a skeleton buried in the cemetery of Porto Ercole, and believed to be Caravaggio’s, reveal that he probably died from sepsis caused by a badly infected wound. Knowing Caravaggio’s tumultuous lifestyle, this is not unlikely. Nor is it surprising, therefore, that his last painting The Martyrdom of St Ursula, in which he portrays himself with upturned face amongst the onlookers, depicts the saint looking down in quiet shock at seeing the arrow’s shaft suddenly lodged inside her breast.

As for a Trump, if you were to apply the ‘contrapasso’ principle from Dante’s Inferno, I guess he will now be relegated to the lobby, not the lobby of the glamorous Plaza Hotel which is no longer his, but a virtual lobby, muted, video turned off by default and desperately waiting, desolate and defeated, for someone to let him in.