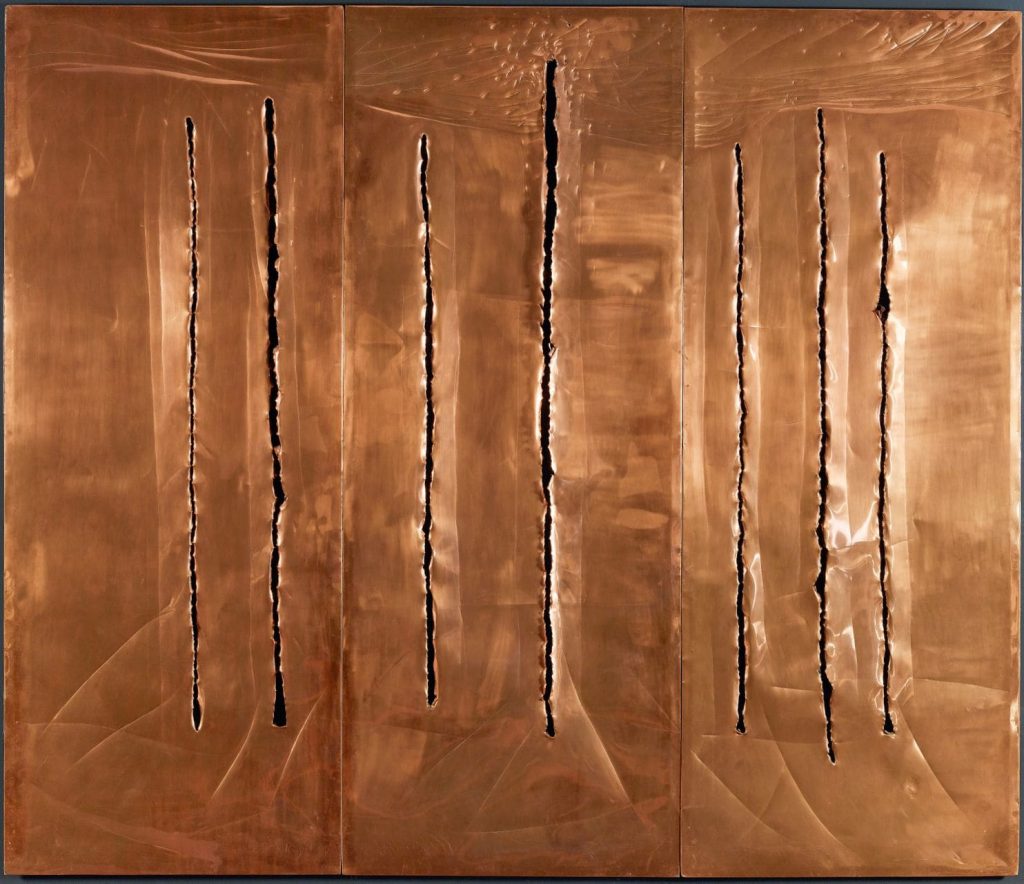

The cuts endure, as does the unknown

Fontana’s elegantly hacked paintings have become visual signifiers of the moment when art began to discard conventional notions of what painting and sculpting needed to be.

The work of Lucio Fontana enjoys the same sensorial acknowledgement as that of a song heard in passing that stops you short in your tracks and the melody of which unquestionably sparks memory: you know it, but you’re not precisely clear about who it’s by, where you first encountered it or why you really, really like it.

But looking at just one image showing his most recognisable slashes – which he referred to as Tagli (Cuts) – would sit comfortably within anyone’s realm of recognition. Ask anybody whether they know of his meticulously painted canvases – many white, a few in earthy tones, some in a brilliant primary colour – with a large laceration or lacerations defiantly peering through to a realm of darkness beyond and they would say – yes, of course I know them.

Fontana’s elegantly hacked paintings have become visual signifiers of the moment when art began to discard conventional notions of what painting and sculpting needed to be. They signify the complex ambitions of Contemporary Art, its need to redefine its own position and assert its role in describing the meaning of the world around us and our place within it. But, truthfully, Fontana’s Cuts came a lot sooner than many of the most prevalent contemporary theories had a chance to really lay claim over the art world. They laid the foundation for Conceptual, Performance, and Minimalist Art simply by virtue of wanting to accomplish a singular, albeit lofty, goal: to meaningfully capture the precise moment in time when they were created and to do so by distilling movement, time, colour, space and sound into one conceivable artistic operation or, as Fontana and his contemporaries put it in their White Manifesto, to capture a “moment of synthesis”.

Despite Fontana’s subliminal ubiquity, his latest retrospective – Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, showing at the Met Breuer until mid-April – is only the second display of his work to take place in New York: the last took place over 40 years ago. Fontana first took a Stanley knife to his canvas in 1958, but he had been punching holes and experimenting with penetration into the fourth dimension for around 10 years by then, marking his visionary movement into gestural art-making at roughly the same time as Jackson Pollock began creating his drip paintings. Needless to say, Pollock has enjoyed categorically superior action in the New York retrospective shows department. Still, the show at the Met Breuer serves to soundly – if succinctly – cement Fontana’s unmistakable, and multi-layered influence on Contemporary Art.

It does so not without allowing viewers a brief glimpse at what came before the artist’s most renowned breakthrough: his early days, working primarily as a sculptor, occupy the precursory rooms in the exhibition. Sculpture was the backdrop to Fontana’s upbringing. His father was a funerary sculptor working in Rosario, Argentina, making tomb sculptures for local cemeteries. In his twenties, he moved to Milan, Italy and received classical training in carving at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts.

But, as evidenced by the works on display in the show, Fontana’s sculpting predilections favoured brazen, perceptible modelling rather than classical carving. He worked like a Baroque sculptor in a hurry, exuding zealous motion whilst sublimating influences from Etruscan sarcophagi and Futurist sculpture into figures and objects that at once revere and defy all art movements that came before them.

Moving through the exhibition, it is easy to feel as though you are searching for Fontana’s eventual signature style – conditioning your eye to recognise a glimmer of what is inevitably to come. You can palpably feel the artist searching for the means through which to signify the true expression of the universe: a visual search to put an end to what he would eventually declare as man having “exhausted pictorial and sculptural forms of art”.

You can feel him getting there once your reach his Buchi (Holes). Textured, seemingly extra-terrestrial, terrain is poked, punctured and drawn into, creating a topography that provokes and ultimately up-ends dimensionality. By now, Fontana is done with representational sculpture, but he’s not entirely painting. These works are not regular easel paintings; they are devices with which to explore ‘Spatial Concepts’ – which is the apt title he gave to his first perforated works.

The climactic rupturing of canvas finally releases Fontana’s body of work from the realms of experimentation into unequivocal theoretical certainty. It’s no wonder he has been quoted as being “happy to go to the grave after such a discovery”. With one decisive slash, Fontana was now able to contend with the notions of space and infinity, to create an entry point into a new dimension that persists beyond art. He backed many of his cut works with black gauze, intensifying the illusion of endlessness and thus allowing viewers to contemplate what for them is the unknown. Viscerally, Fontana had come far away from where he started, but notionally he was still embroiled in the same preoccupations: achieving the physical representation of existence and its intricacies, of that which is undetermined, of the beyond – perhaps of that by which he had already been confronted with while growing up in the care of a funerary sculptor: death.

Fontana is known to have inscribed the back of his cut canvases with personal messages, varying from the theoretical to the ordinary: an act that reminds us that, despite having achieved an artistic approach which, to this day, feels so categorically resolved, he was still searching, still grappling. This very human exploration is perhaps why so many people know and are drawn to Fontana’s work. Indeed, his cut canvases deliver us to a threshold – one which separates us from what we can conceivably possess and what we cannot because, even though we can now identify the darkness of infinity, we are still nowhere near to understanding it.

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, is on show at the Met Breuer, New York, until 14 April