The abominable ‘female’ artist and her issues

‘For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.’ Virginia Woolf.

Let’s face it: no woman wants to be called ‘female’ this and ‘female’ that. We want to be seen as what we are without any gender references and connotations. Obviously. We consider the simple mention of our gender before our profession to be insulting. But the figures beckon. Some statistics in themselves are insulting – and prevalent across the board.

In Maltese politics, for instance, the proportion of female politicians is set at between eight and 10 per cent and has not budged for the last 60 years and other sectors, such as my own – medicine – fare no better. According to a 2018 report by the Freelands Foundation, fewer than 30 per cent of artists represented by major commercial galleries in London are women, with only five per cent of galleries representing an equal number of male and female artists.

Tate Modern director Frances Morris curated landmark major retrospectives of women artists including Louise Bourgeois (in 2007), Yayoi Kusama (in 2012) and Agnes Martin (in 2015) before her present appointment. Does it take a woman to organise exhibitions of female artists’ work? Do most male curators still naively – or deliberately – ignore female artists as they have done since the cinquecento?

Rome’s Palazzo Braschi and the Museo del Prado in Madrid recently held major solo shows of Artemesia Gentileschi and Flemish Baroque prodigy Clara Peeters respectively, whose work is selling with million-dollar price-tags: a few female drops in a sea of male artists.

Lately, it seems that, in the art world, women’s voices are heard more loudly in the Middle East. Last December, The Art Newspaper claimed that the art ecosystem in the Gulf is dominated by women. Royal patrons, expatriates and home-grown professionals are leading cornerstone institutions and driving the art market in that part of the world. So, what is the situation in Malta?

Female students studying art outnumber male students at the University of Malta and at MCAST, and have done for a while. Women are not absent from key positions in institutions such as the Arts Council of Malta and most private art spaces in Malta are run by women.

And yet, at the newly inaugurated MUŻA in Valletta, of the hundreds of works on display, only seven are by women. Seven works out of a collection of thousands! I know that many more works by women are part of the national collection, so why aren’t they on show? MUŻA is a national-community art museum, boasting open, non-linear curation and a welcoming ethos, however its collection is a historical one, and it cannot rewrite art history overnight.

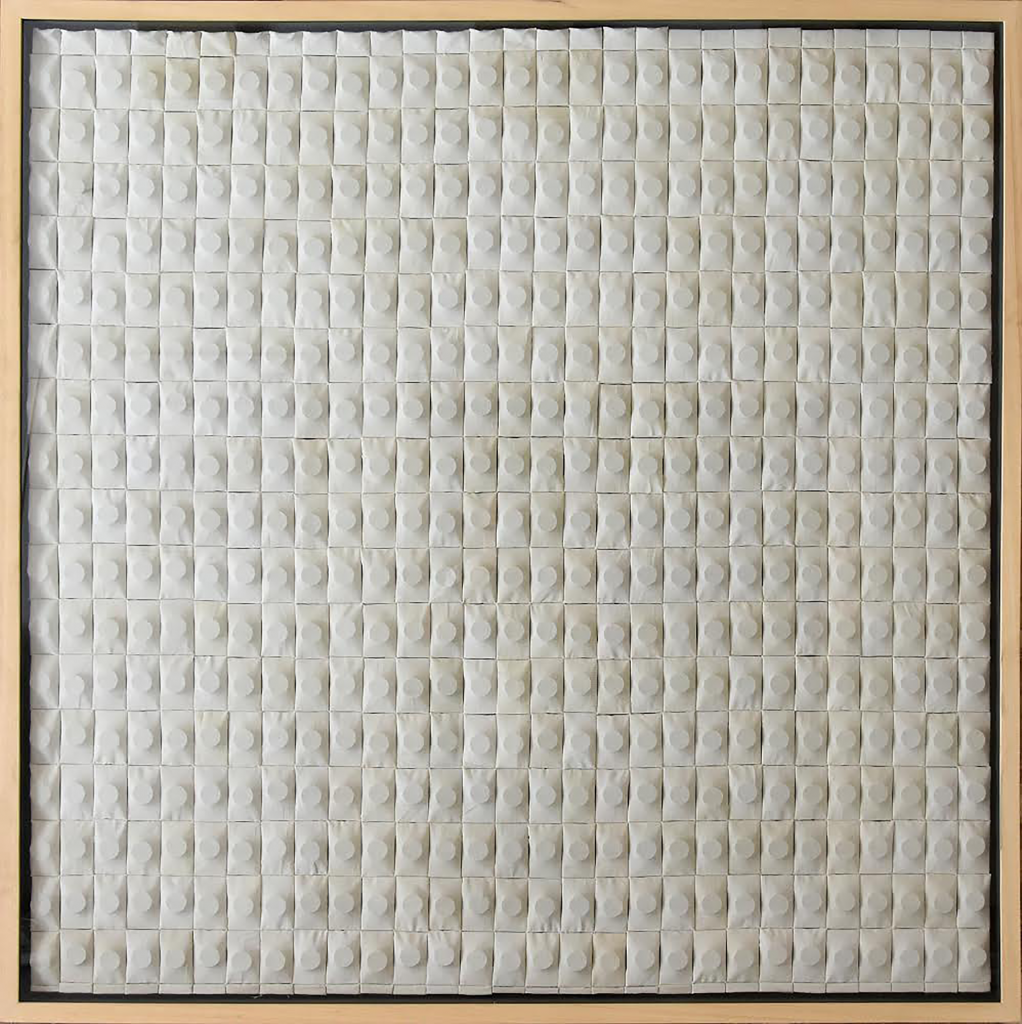

Teresa Sciberras, a prolific artist who trained in Scotland and Italy before completing her MFA at the University of Malta, remembers: “When, in 2017, the artist line-up for the Malta Pavilion was announced, I couldn’t help but notice that from the local artists, I was the only woman. The other three women artists who participated in the exhibition were from the Maltese diaspora. The female co-curator, Bettina Hutschek, is German. Coincidence? Maybe, but definitely one that gives pause for thought. I’m 100 per cent sure that this was not due to prejudice on the part of the curators, so then what was it? Why is there such a stark and obvious discrepancy?’

Why are there so few works by female artists on display and in permanent collections? Why do female artists find fewer gallerists to represent them? Why are retrospectives of female artists so much less prevalent than those held for male artists?

Does this discrimination begin at school? Chelsea College of Arts graduate Chiara Cassar thinks not. “I actually think that art school is a huge safety blanket and creates a ‘deer in the headlights’ type effect because you have so much time to focus on your art practice, that you forget about the future struggle you will be faced with when you leave art school.’

Her contemporary, Maxine Attard, says: “But, as in all parts of the world, girls and women are put in second place to men and forcefully – or softly – groomed to fit into a female stereotype. In my education in Malta, I was never told I could not do something because of my gender. I always felt that I was seen as someone special because I was a woman and wanted to be a serious artist. I never experienced such comments or felt such perceptions during my studies in the UK.”

And why do female art school graduates exhibit less in the first five years after graduating than their male counterparts? Are they as prolific? Or is it just a matter of their work not being included in exhibitions? London-based, Royal College of Arts graduate Roxman Gatt tells me: “In my view, all women are prolific; they have had to work way harder than men and continue to do the same work, but what they achieve is beyond exceptional. The weight that the work carries is very visible: you can see the struggle, the passion – the transparency. It took many strong women to help us pave the way to an easier place, but the battle is still on-going and SHE will still be thrown obstacles and belittled and silenced; however, SHE is born a hustler and will always be one.”

But why do collectors buy less art from female artists? Is it because their art is ‘female’ or ‘girly’? Is it because it explores – or is perceived to explore – ‘female issues’ or issues with the ‘female identity’? Female art? The work of the late Isabelle Borg, for example – a pioneer and heroine of the modernist movement in Malta – certainly does not subscribe to the description ‘female art’.

On the other hand, artist and film-maker Charlie Cauchi says: ‘My work is all me… so I suppose I do approach things from a female standpoint. I do deal with very personal material.” But Maxine Attard believes that: ‘No, my gender is not reflected in my work at all. This is another issue that women artists have to face. Women tend to be asked if their work is autobiographical. Male artists are never asked such questions.”

Is the absence of work by female artists in shows and museums linked to collectors and their gender? In a Huff post article, Malcolm Harris comments: “Unlike their boisterous and boastful male counterparts, most female collectors are very discreet in their purchasing habits and rarely make public announcements about the works or artists they are collecting.” Perhaps it is the humility factor once again that is keeping women back.

There’s also the factor of female artists simply being less known than their male counterparts. Although the Art+Feminism movement has seen more information about female artists than ever before uploaded onto the public domain, there is still a long way to go in this area.

“Give me your opinion”, I said to several artists. “I want to get the gist of how you feel.” How many more centuries of unfair bias in the art world do we have to endure before we start questioning the relevance of this bias? “I don’t feel anything about it that makes real sense”, some said. “I shouldn’t have to have an opinion and, anyway, my opinion doesn’t matter much because there is no rational reason and no explanation for these statistics” they said. And I agree. Sexism is irrational by definition.

“The thing that niggles most here, however, is that over the last few years – with a few notable exceptions – those who seem to make it out of that sticky, endless ‘emerging’ tunnel seem to be the boys. They are greeted with slaps on the back from the older, established generation of male artists; they engage in the competitive bravado of who’s the best new kid on the block”, says Teresa Sciberras. Roxman Gatt says: “I would be naive to think that gender disparity in the art world no longer exists. Women are still tragically under-represented in the art world and commercial gallery sector and the pay gap still persists in universities and other large institutions.” So, what do we do?

First, we must identify the reasons for these statistical gaps. But, as Teresa Sciberras says: “I don’t yet know what exactly this gap is, much less how we can escape it. Can we build a bridge over it? Is it a gap that – in order not to fall into it – a woman must give up something of themselves: the possibility of love, perhaps, or a relationship, or having children? Maybe, in order to be an artist we must shed something of these like ballast from a sinking air balloon, in order to emerge and join the establishment.”

Will the gaps shrink if we shine more light on female artists: consciously, frankly and discriminatorily? Is there something wrong with intentionally balancing out gender presence and representation in the art world, especially when there are more artists graduating from the gender that is so grossly under-represented? Will unofficially designated quotas affect the respect these artists deserve in their own right, as quota-assignment has done in other areas?

I suppose we should not be having this conversation. We certainly should not have to have this conversation – but we must!