EX AERE

In memoriam of Joseph Chetcuti. By Lisa Gwen Andrews

Stepping into the Luqa foundry, I sense his lingering presence. The wondrous space, with impossibly high ceilings, is a delicious amalgamation of clutter and heavy-weight machinery, which juxtaposes three-dimensional works, portrait busts, plasters and reliefs placed on various surfaces, and hung on the walls. This is what a workshop / artist studio should look (and feel) like. This is the kind of space in which magic happens on a daily basis.

Chetcuti’s memory needs to be placed firmly into context, as his creative output provides a strong and meaningful contribution to the evolution of Malta’s artistic history

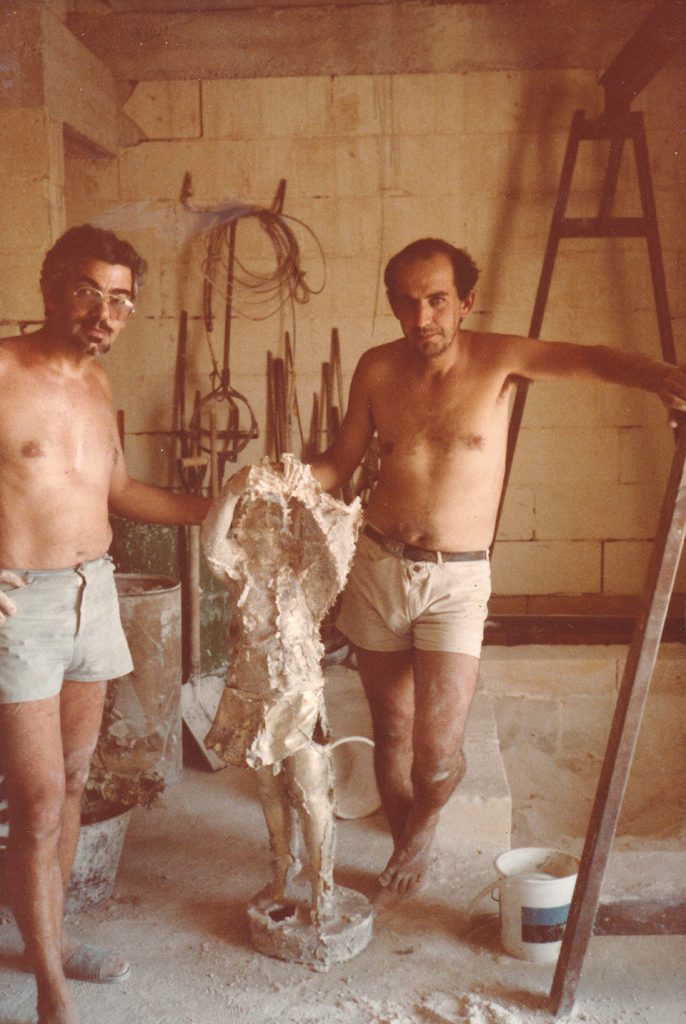

After taking in the cavernous space, I take a closer look and start to notice the details; my eyes rest on all the photos affixed to the interconnected spaces. Chetcuti is present in all of them, and in many others, one or more of his sons feature prominently. Christopher, his eldest, who has now taken over his father’s business, often captured alongside him.

Upstairs, I am shown around the study, and what seems to be an open plan space that once housed life-drawing classes. Dozens of maquettes, plasters, drawings and paintings once again punctuate the room. The three-dimensional works fight for attention on the industrial shelving, so much so, that many others are lined across the floor. I recognise a few faces of past sitters; others, I can only wish I recognised, or knew, such is their stance and air of sophistication.

I am allowed to sift through hundreds of photos, of an innumerable number of sculptural works produced over the decades. I almost feel like I am trespassing on intimate memories. And yet, I can’t help but wonder…. for such a prolific bronzesmith, and a sculptor / artist in his own right, why was Chetcuti such a low-key character? His reserve might be the reason why his name hardly ever showed up in exhibitions, or why the foundry is mostly known to a tight circle of artists and individuals working directly in the field. In fact, Chetcuti only participated in a handful of exhibitions and collective shows; between 1985-1998 he was active on the Lljieli Mediterranji platform; in 2014, he organised his first and only solo show at the Malta Government School of Art. The last exhibition he participated in was in 2018, titled ‘Tactile: 12 Concealed Sculptures’, the exhibition, which was held at the Valletta University Campus, played on the senses through a series of works produced by Malta-based and international visual artists.

Having originally been trained under Vincent Apap in Malta, in his early twenties, Chetcuti was awarded a full-time scholarship by the Italian government to attend the Accademia delle Belle Arti, in Florence, where he furthered his practice-based studies in drawing, modelling and sculptural design. He spent as many as five years in Italy, studying, training and later also following an apprenticeship in the studio of the Italian portraitist and sculptor Pietro Annigoni (1910-1988). During his stint in Florence, he also attended the Scuola Libera del Nudo.

On his return to Malta, Chetcuti first started working in carpentry, specialising in wooden sculpture. It was only in the early 90s that his attention turned to bronze. Having originally set up shop in the basement of his marital home, Chetcuti, with the support of his family, slowly acquired a plot of land in Luqa, which he transformed into the foundry. The sculptor Frans Galea (1945-1994) was a close friend and became one of the first clients, entrusting him with several bronze works. Branded as Funderija Artistika Chetcuti, Chetcuti’s is the only remaining active foundry present in the Maltese islands that can produce artistic works.

The foundry was Chetcuti’s livelihood; designed and built according to his specifications, it became fully operational in 1993. The space was, and still is, home to countless projects, commissions and collaborations which vary greatly in terms of complexity, assembly and production processes. Having worked alongside his father since 2009, Christopher recounts how there were as many as four full-timers at any one time working on the larger and more demanding of commissions, such as the monument dedicated to Grandmaster Jean de Valette, located in the square flanking the Old Opera House, now known as Pjazza Teatru Rjal.

That is only one of many monuments and statues which Chetcuti and his foundry was responsible for creating and casting. Other important projects worth mentioning are: the Immaculate Conception, which can be found in Bormla; the statue for Winston Abela in Zejtun; the papier mache sculptures for the Church of Our Lady of the Lily, in Mqabba; the statue dedicated to Mater Dei by Chris Ebejer, at Mater Dei Hospital, which is their largest work, ever cast; The Three Graces, in Mgarr, Gozo designed by Andrew Diacono, or even the mezzafigura by Vincent Apap of Giuseppe Calì, at the Upper Barracca Gardens in Valletta.

The foundry also produced important replicas: of Alessandro Algardi’s Christ the Saviour which can be seen above the main portal of St John’s Co Cathedral in Valletta as well as a bronze replica of Antonio Sciortino’s poignant sculptural group, Les Gavroches, located in the Valletta Gardens, where the original once sat.

There are few of Chetcuti’s works extant in private collections, such as a sinuous nude lying on her side titled In a Pensive Mood. His wife Nathalie and his family have a grand stallion he made, caught in motion; however other works that the sculptor exchanged, are harder to record, or come by.

Chetcuti’s memory – whether as a sculptor, or as a bronzesmith – needs to be placed firmly into context, as his creative output provides a strong and meaningful contribution to the evolution of Malta’s artistic history, in more than one instance: through the safeguarding of our artistic heritage, but also through the production of contemporary sculptures and public artworks.