Blind Faith

Interview | Matthew Attard | Malta Pavilion | Venice Biennale 2024

Imagine, if you will, looking out to an infinite blue horizon; in the haze of the sea you catch sight of an island. Eventually, the ship that you’re on reaches land and you come ashore, thankful to have survived another journey – skirting storms and worse – to set foot on land, and to be home. Later, as the movement of the sea ebbs from your legs and you regain your balance, you walk for the sheer relief of it, and as you stand in the shade of a chapel overlooking the Mediterranean Sea you feel an urge to record that moment. You take a small metal tool from a pocket, and you start to carve into the soft stone of the wall. You draw the lines of a ship, taking time to outline its prow and stern, and its tall upright mast. You hope that this act will keep you safe when you leave these shores again.

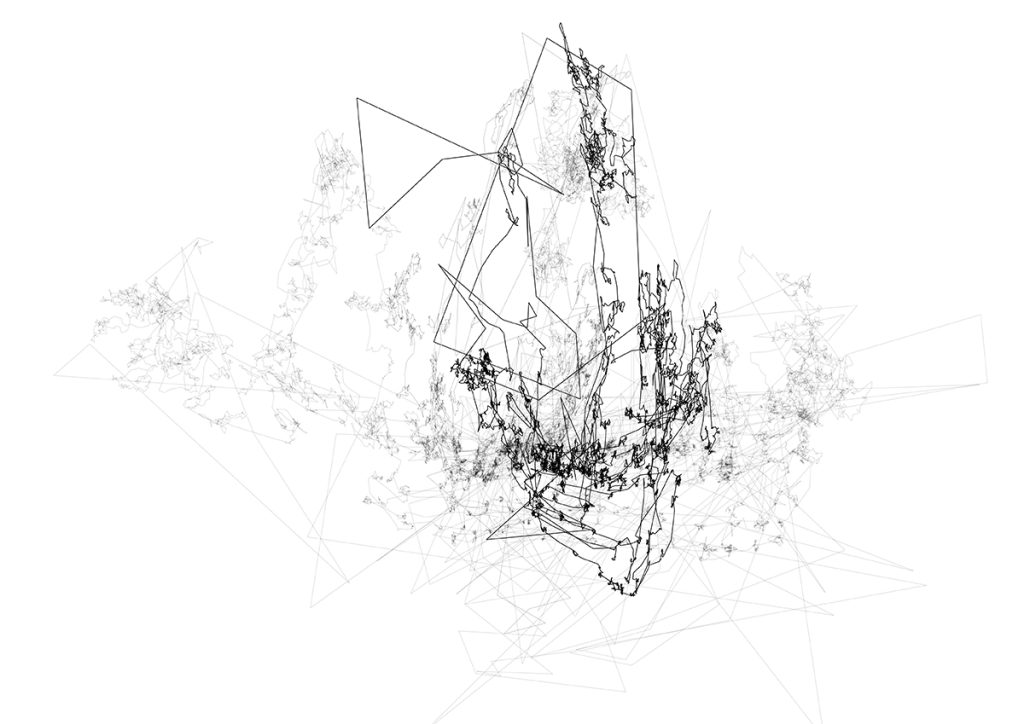

I meet Matthew Attard in his studio in Rabat, just outside the ancient Maltese city of Mdina. With him is one of the curators and long-time collaborator Elyse Tonna who has been working through his ideas with him for several years. Laid along the length of his workspace are rectangular slabs of reconstituted stone, and on the surface of each is a ship (on some are two or three) drawn in jagged straight lines, the form of a vessel sometimes difficult to make out. On a table nearby is a pen-plotter, the tool that Attard has been drawing with; more accurately it is the tool that has allowed him to plot the data from an eye-tracker which he wears and which records the movements of his eyes, effectively ‘drawing’ with his gaze. Attard has been wearing the eye-tracker as he follows the lines of one of the many anonymous ex voto ship ‘graffiti’ dating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century found on stone walls around Malta, working with it to create these linear ship-like shapes. Because the eyes – or so he tells me – are unable to travel in curved lines, but rather dart from point to point in what are known as saccades, his drawings have a pointed, but strangely delicate quality, with lines fanning out from each other from one point to another, forming sharp rises and falls.

But how does an artificial mind understand the shapes, and what does it see when it identifies a ship?

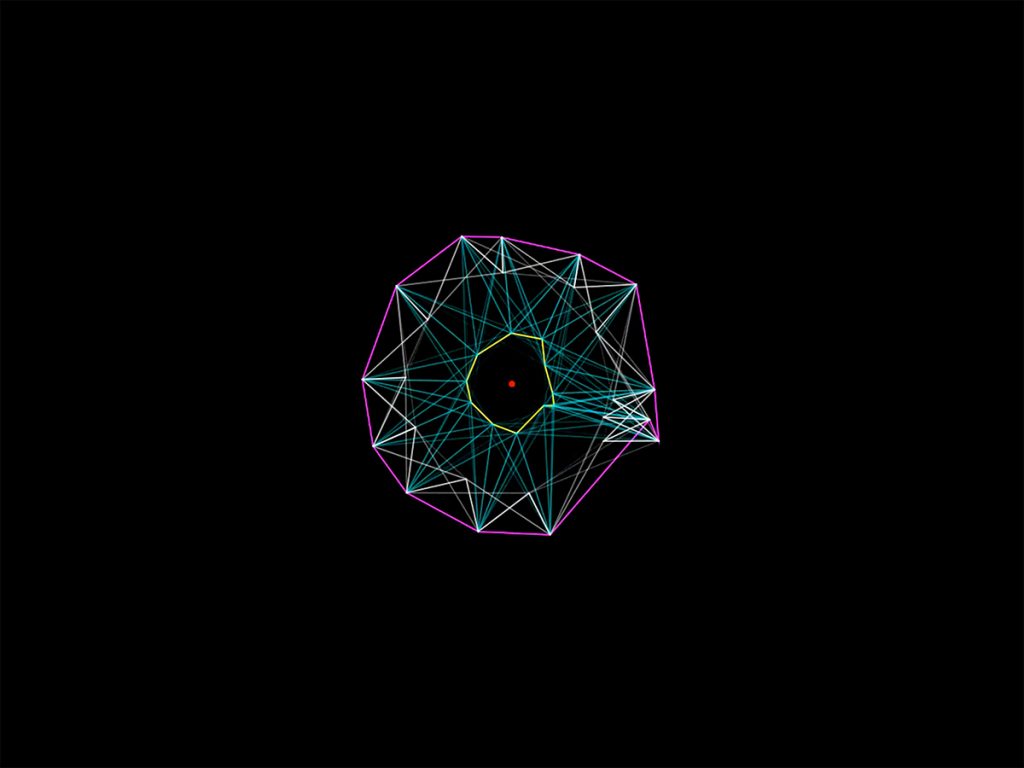

Together, the ships form a fleet – sailing on a wall of stone instead of water. And this wall forms what is probably the most physical – and tactile – element of Attard’s work in the pavilion. Together, he and Tonna tell me more about the images he has been creating, using digital technology to produce even more iterations of ships, digging deeper and deeper into the essence of the thing – the very shipness of it. The lines and points are placed together to form a prow and a stern, or a mast, which the human eye recognises as a ship. But how does an artificial mind understand the shapes, and what does it see when it identifies a ship?

But Attard isn’t simply playing with digital toys. He thinks intensely about the act of drawing – the meaning of what it is to make a mark, to form a shape with a line, what it means to deconstruct the act of putting pencil to paper. He tells me drawing can never be defined, because ‘once you define it, you exclude its infinite possibilities’. He talks about drawing as a never-ending act, an iterative progression like a wandering (or sailing) into the unknown, and a generative process in its own right.

He thinks about what the act of drawing in stone meant to those who carved the outline of a ship on a soft limestone wall; the act of drawing as an act of hope, relief, gratitude, bargaining: ‘take this drawing God, but leave me my life’. He thinks about his own practice, this ‘drawing with’ that he does every day – drawing with pen, with pencil, with eye, with machine, with x-and-y axes, with air, with information, with data points, with time.

Our conversation goes back to digital technology, back to data points and algorithms, and to constantly questioning the connection between the mind and the eye or the hand and the machine. Attard shows me images of what will be a huge screen, a landscape of liquid images – almost a metaphoric sea of data. This shifting image is a generative piece, feeding information back into itself, constantly searching for meaning in the form of a ship to emerge from the sea. The fluctuating imagery (itself made from a series of images of the sea that slowly morph into each other) interferes with the digital mind’s understanding of what it sees, meaning that it’s constantly engaged in a never-ending search for imagery.

Attard’s work is not the slick, stylised aesthetic we have come to expect from AI-assisted work. It is delicate, almost serene, its straight lines are feathered and blurred. It lives in the liminal spaces of AI, somewhere beyond the hype and the gimmicks in its own landscape. It’s ever-shifting, ever-changing, creating something from nothing. It makes lines from a glance and forms shapes from data-sets, in a continuous search for meaning.

And so, we come around to the convergence of historical and contemporary technologies; a chisel to carve a line in stone, and a set of information points converted into a line on a screen. Attard’s ideas zigzag back on themselves, from technology to thoughts and back again.

Attard questions the role of technology and our tethering to it, and our easy surrendering of our most personal and most banal secrets. It would be simplistic to interpret the work as creating an analogy between a god of medieval votive offerings, and an all-seeing ‘god’ of technology but there is something in this examination of how we surrender our thoughts to something less tangible even than water. In following the outlines of these ancient, anonymous drawings, equipped with eye-tracking headsets, and later his pen-plotter, Attard is drawing on history and human faith, working through ideas of fear, migration and human endeavour.

These themes have long been present in Attard’s practice. His 2021 solo show rajt ma rajtx … smajt ma smajtx (I/you saw but I/you did not see … I/you heard but I/you did not hear) at Valletta Contemporary and curated by Tonna, was a commentary on the Maltese state, on blind faith in politics, and the omertà of silence. Here the eye-tracker played a different role; that of witness to socio-political realities. His 2023 exhibition Ship of Fools at Galleria Michela Rizzo in Venice, allowed him to continue this line of research, questioning belief in iconographies, and substituting a digital palette and brush, with the brash emoji, now ubiquitous in our online conversations.

This new body of work – which speaks also to the title of Stranieri Ovunque (Foreigners Everywhere) given to this year’s Biennale by its curator Adriano Pedrosa – allows Attard to take his experimentation even further, with more complex digital tools, but also a continuation of his thinking through human behaviour, our relationship with technology, and our hopes for the future.

Matthew Attard represents Malta at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia 2024. The pavilion is co-curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini, project managed by María Galea and Michela Rizzo and the software is developed by Joey Borg.

The Maltese Pavilion is commissioned by Arts Council Malta (ACM) under the auspices of Malta’s Ministry for the National Heritage, the Arts and Local Government. The Pavilion is being project led by the Internationalisation team at Arts Council Malta, headed by Dr Romina Delia and supported by Celine Portelli (coordinator) and Dr Frank Psaila (PR Internationalisation) and Maria Angela Vassallo (Head of Communications). The Evaluation Board members were Perit Adrian Mamo, Artistic Director at the Manoel Theatre; Dr Katya Micallef, Curator at MUZA (the Malta Community Art Museum) and Daniel Azzopardi, Artistic Director of Spazju Kreattiv. The evaluation was chaired by Mary Ann Cauchi, Director of Funding and Strategy at Arts Council Malta.