Anish Kapoor: Works, Thoughts and Experiments

There are few living artists of our time who have achieved the recognition and the renown that Kapoor has attained during his career.

In a now legendary photomontage from 1960 entitled ‘Leap into the Void’, the French artist Yves Klein depicted himself in an act of gravity-defying will. He is seen to be leaping off the ledge of a building only to, we may assume, plummet down to the Parisian street three stories below. But the image is only an illusion. By capturing the artist in suspended motion, the photograph presents itself as a singular moment frozen in time. In fact, Klein furtively manipulated the viewer’s credulity by compositing an existing photograph of the artist merely falling into a waiting safety-net on top of another image depicting the empty street below, thereby only making it seem as if he had taken this defining plunge into the void.

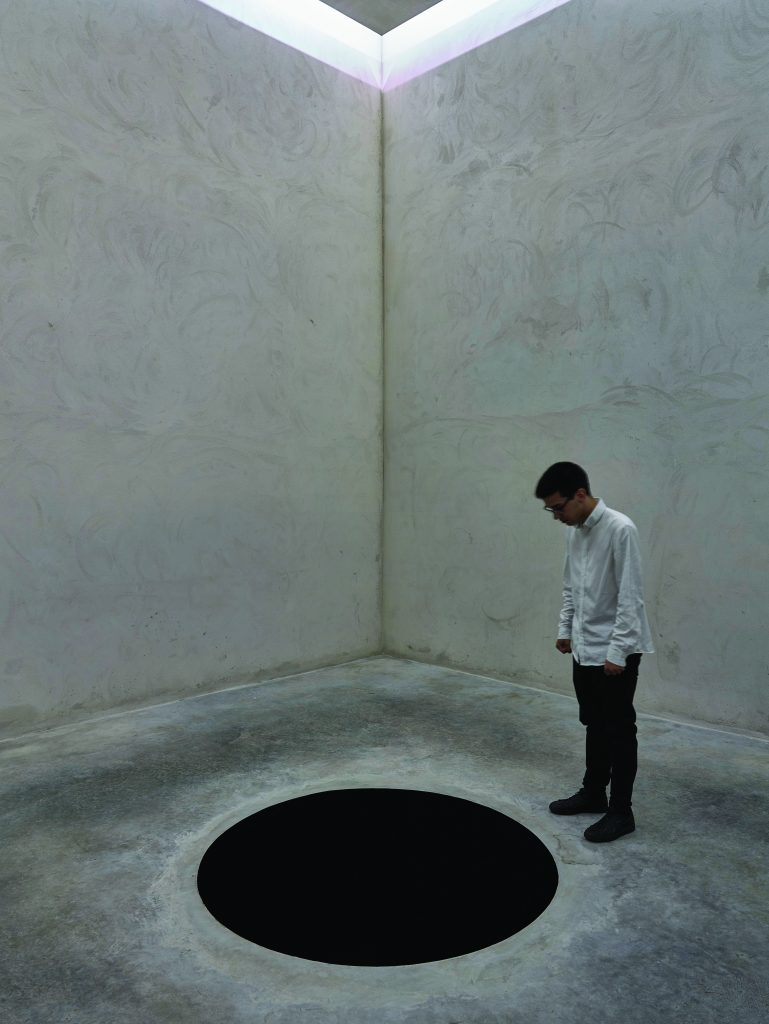

In the work of Anish Kapoor (b. Mumbai, 1954), however, we are often faced with the very real proposition of sinking into some bottomless pit or being made to contemplate the incomprehensible notion of the infinite. As a sort of mental exercise, try to truly picture infinity – to really imagine the boundless expanse of endlessness. If you dwell on it long enough, your palms start to sweat and your heart races. It is almost unnatural – or even impossible – for a mere man to try and envision such things. Yves Klein once proclaimed: ‘I believe that fires burn in the heart of the void as well as in the heart of man.” Kapoor believes in this too, only in his work this burning void is calibrated at a different level of intensity.

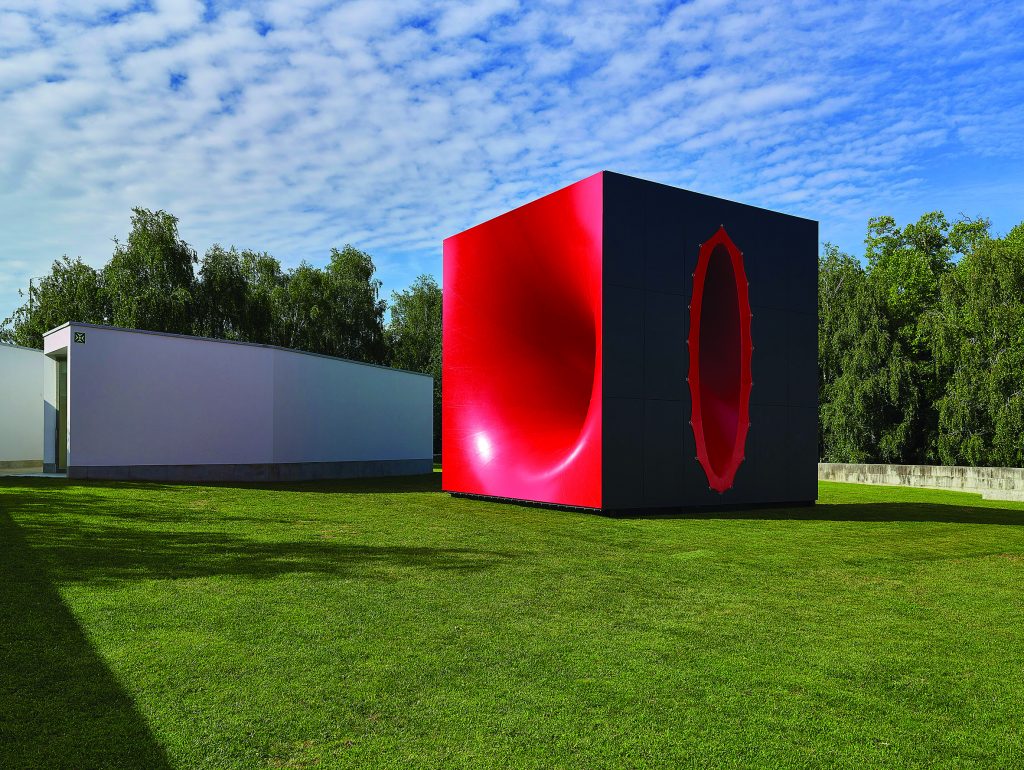

Kapoor’s vast and profound body of sculptural work has been conceived for – and on the scale of – bodies, cities and the landscape, and the myriad contexts in which they are located, from the urban scale of metropolitan centres such as London, Naples, New York and Chicago to the rolling hillsides of England and New Zealand. In recent years, he has also been invited to present his work in some of the world’s most beautiful formal gardens, including London’s Kensington Gardens and the Palace of Versailles in France. This year, the beautiful gardens and museum of the Serralves Foundation in Portugal will play host to this seminal artist, offering viewers a platform of a different historical and spatial dimensions from which they will be able to see his work in new and surprising ways.

The Serralves Museum, situated in the historic surroundings of Porto town, is a true cultural gem. Its art deco villa, designed by architects Charles Siclis and José, Marques da Silva, is set against the formal gardens designed by the renowned French landscape architect Jacques Gréber, as well as romantic gardens, fields and a farm. And a contemporary museum building, library and auditorium, designed by Álvaro Siza Vieira, is considered one of the foremost integrations of contemporary and historic architecture and landscape in Europe.

In this unique setting, the exhibition presents a selection of outdoor works that are representative of Kapoor’s sculptural language in which materiality, scale, architecture, the landscape and the viewer are all integrated through a cohesive and wildly ambitious creative vision. The choice and location of sculptures in the Park of Serralves have been carefully considered by the artist to create an itinerary through time, space, perception and meaning.

The accompanying presentation of 56 models of realised and unrealised projects conceived over the past 40 years in the central exhibition space of the Serralves Museum returns us to the intimate scale of the artist’s studio as a space of thinking and experimentation

There are few living artists of our time who have achieved the recognition and the renown that Kapoor has attained during his career. A relatively meteoric rise to prominence as part of a generation of young British artists in the 1990s helped cement his reputation as one of the forerunners of an associated group of practitioners active on the London art scene. However, his work has always stood somewhat apart from his contemporaries, not only for its characteristic earnestness and lack of irony (most unusual in these jaded, cynical times) but also for its deeply embedded roots in rituals, aesthetics and points of reference that are far removed from the historicised idioms at play in much of the sculpture of the time.

Instead, Kapoor’s early works (mounds of vividly coloured pigments and deeply saturated esoteric forms) transport us to the market-places and temples of India, the country of Kapoor’s youth and heritage and that influenced so much of his own upbringing and helped inform his later cultural identity as an immigrant to the U.K. While his later work would tend to be more immediately visceral, capturing the viewers’ attention through the sheer visual impact and sensational manipulation of scale and form, his early work retains an almost deferential nature, in spite of its attention-grabbing use of colour derived from the spices and pigments often sold from large mounds on Indian street stalls. It seems to speak to the elemental nature of sculpture itself, propositioning the use of ephemeral substances such as powder in place of the imposing, purposefully permanent materials of Western art history like marble and steel.

If Klein’s art was informed by the occult Rosicrucian belief in space as ‘Spirit in its attenuated form’, rather than an empty void, Kapoor aligns his own practice to the divergent Buddhist philosophy that the void is a plenum rather than a vacancy – a space engulfed by matter and the potential for transformations, changes, ends and beginnings.

In relation to this concept of the void, Kapoor observes: ‘You cannot enter the void, but viewing gives prospect to the wholeness it contains.’ Therefore, the act of viewing becomes a creative act in itself: the energy of this void, which Buddhists describe as ‘shunyata’, can only be approached through the abstracted directions and propositions provided by poetics, examples of which include the paradoxical songs of the Siddha adepts and the riddling koans of the Zen masters. In the same spirit, the large-scale sculptures on show at the Serralves Foundation do not provide a range of spectacle-endowed objects so much as a variety of propositions, staging complex reconfigurations of space and perception.

Kapoor draws inspiration from a deep well of mythological sources and his work, for all its technical virtuosity and contemporary resonance, recalls the ancient Greek idea that the artist who seeks a sense of perfect understanding of nature risks posing a challenge to the gods, who regard creation as their prerogative alone, with the jealous Goddess Athena turning the weaver Arachne into a spider and Apollo having the flute-playing satyr Marsyas flayed alive as punishments for their impertinence.

Kapoor’s own reverential approach to the elemental forces of space and time, however, seem to seek a harmonious reconciliation with nature rather than seek to provide an imitation or recreation of it. It would not be fair to judge Kapoor’s work on such a basis alone. After all, artists are not defined by the mythologies they inherit; rather, they serve to revitalise and extend existing mythologies through acts of choice and making. As Kapoor himself observes: “Artists don’t make objects, artists make mythologies, and it’s through the mythologies that we read the object.”

One contemporary mythology that still holds much currency in today’s ever more interconnected world is the nationalistic concept of cultural identity. In contrast to many of the localised sculptural practices that preceded him, Kapoor takes a dynamic and fundamentally trans-cultural approach which aims to establish some sort of affinity between the practices of different sets of people, belief systems and cultures. In doing so, he suggests that a trans-cultural, or global, approach does not necessitate the loss of personal identity but rather the enrichment of identity through – and interaction and engagement with – the cultures of others, indicating opportunity for growth within an increasingly globalised, yet ever more personalised, future.