Against Interpretation – Can AI be Creative?

The combination of artificial intelligence and creativity is taking centre stage on all platforms, and in many fields. From Sotheby’s auctions to MIT laboratories, artists, researchers and business managers alike are striving to make the most of out the (relatively) new and promising binomial. Erica Giusta investigates its potential consequences on the perception of contemporary art, asking – will AI lead us ‘against interpretation’?

As recently stated by Arthur Miller in The Guardian, “machines are redefining what it is to be living, not merely human, beings”. And they are raising a lot of questions in doing so. When it comes to art and creativity, the most popular hypothesis, surely, is if these intelligent machines can really be creative – which forces us to question what creativity is in the first place. Cognitive science and evolutionary studies offer a solid and painless answer to what could otherwise degenerate into an endless speculative debate. According to philosopher Daniel Dennett, “creativity is not confined to evolution in nature, but appears to be a pervasive feature of evolutionary processes in general”. In other words, anything and anyone capable of undertaking an evolutionary process is also capable of developing creativity. It comes as no surprise then that today’s AI, equipped with artificial neural networks that work out the ‘rules’ as they go along rather than being taught, display creativity as they find unexpected solutions to complex problems and manage to create something new, original, of potential artistic value.

For the time being, two main forms of AI-driven artistic processes have emerged and sparked people’s interest: those questioning and testing AI’s role at large, taking into account a number of social, economic and political factors; and those exploiting the seemingly inexhaustible power of the machine to startle and amaze, to break a world record or become a ‘first’ in history, from the AI-generated painting sold at Christie’s for more than four hundred thousand dollars, to the first solo exhibition of a robot at Oxford University earlier this summer. What the two have in common is the focus on the production process and what art critics usually identify as form as opposed to content, or rather, the appearance and materiality of the final outcome.

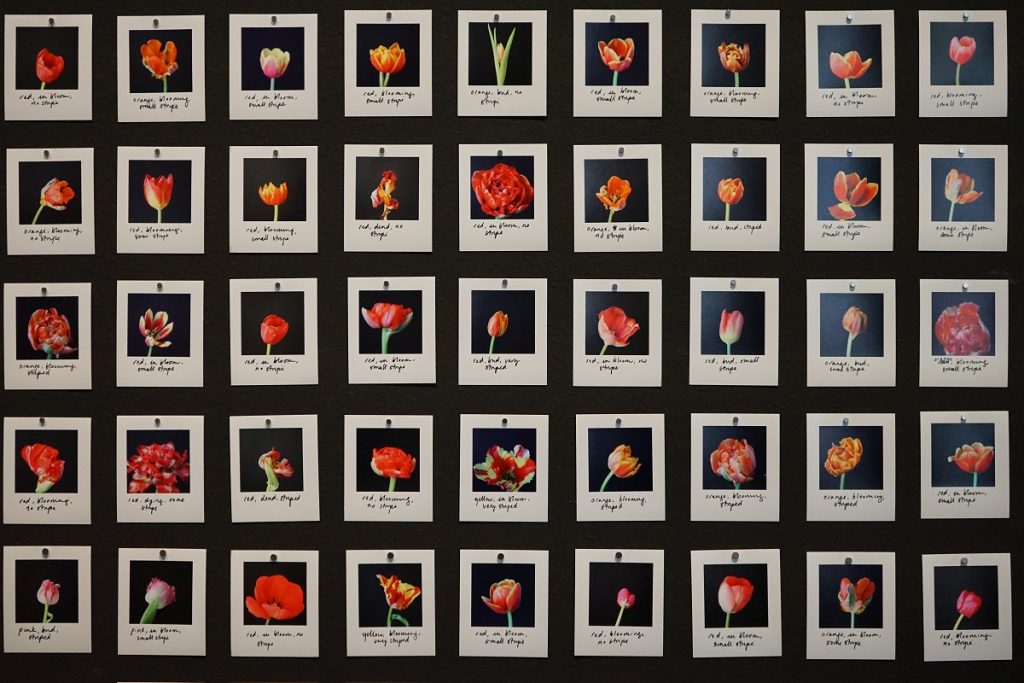

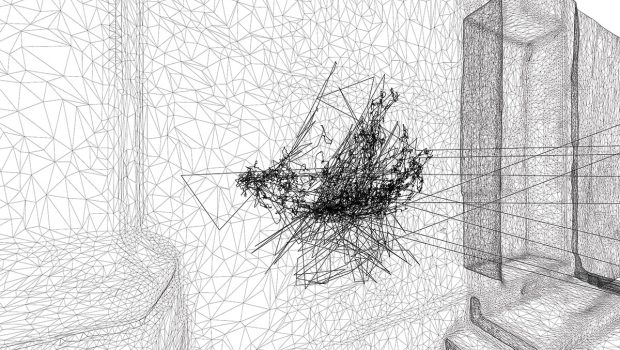

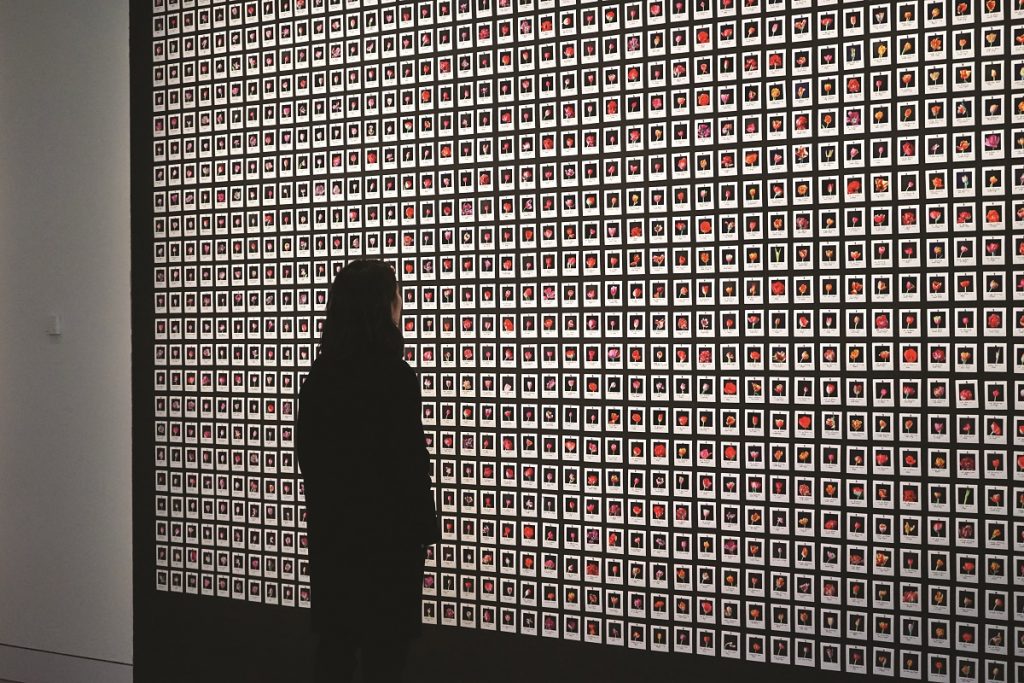

Visual parameters are central in the coding processes of all AI generated works. In Memory of Passerby I by Mario Klingemann, for instance, it’s easy to guess what the training set of the GAN (Generative Adversarial Network – an AI system with two neural networks, one correcting the work of the other on the basis of information fed to it by the user, generally referred to as ‘training set’) in use looked like. Klingemann trained the machine on a mixed set of works of art from European masters from the 17th, 18th and 19th century, a very curated choice to assure a consistent aesthetic to the everchanging final outcome. With Myriad (Tulips), Anna Ridler transformed the thousands of photos that she took – catalogued and used as the training set of her work Mosaic Virus – into a piece of art in its own right, to both show the enormous human efforts (still) required by generative systems, as well as to ennoble the production process as something of great artistic potential. These and many other works were discussed at the Barbican in occasion of the exhibition AI: More than Human, while the humanoid robot with artificial intelligence named Ai-Da was celebrated in Oxford for managing to produce a series of beautiful drawings, paintings and sculptures which look like art. But were they?

Even though the debate generally tends to revolve around the artistic validity of the processes of production of generative art, the aesthetic qualities of its final outcomes are always central to deciding what should be considered art in the first place. As a result, the process and the form of the work of art suddenly becomes more interesting than the content, over which critics and intellectuals usually obsess in their mission to validate art with their interpretations. The conflictual relationship between form and content seems to slowly resolve itself in an almost organic way: the artist expresses them both as a whole, at all stages of the process, from choosing the data for a training set to adjusting the algorithm. The artist as a scientist exploring new boundaries of originality doesn’t need any interpretation, any validation.

Borrowing Susan Sontag’s words about cinema in Against Interpretation, these AI pioneers are “making works of art whose surface is so unified, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be…just what it is”.