Charting new territories, everywhere

The Biennale Arte 2024 in Venice as seen by Andrew Borg Wirth

Last October, as tutors in the Faculty of the Built Environment we presented to students of architecture the brief for their first design workshop of the year: ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, the theme of the, then upcoming, Biennale Arte in Venice. We wanted students to unpack the theme chosen by the designated Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa, investigate his self-declared interest in the artwork by French feminist collective Claire Fontaine and the title of the work which had inspired it. The theme encapsulated our zeitgeist. With it, came an opportunity to understand what role we – architects, artists, curators – were to play within our changing world.

In anticipation of the Venice Biennale Arte opening a few months later, the students speculated on sites across Malta, presenting their own musings on the status of the foreigner and how it came to form their own architectural nous. Effectively proposing pavilions across Malta’s landscape, this exercise was a new way to intersect with a contemporary conversation.

Months later, I find myself walking along the canals of Venice. I cannot help but forge connections between what the students in Malta did and what I have come to Venice to see. The perspective of foreigners referred to in this year’s Venice Biennale is one that positions them in a different realm to the common tourist – foreigners are here complexified. They possess various specific imperatives, departing from the foreigner as the typical holiday-maker leisurely spending time in a foreign country. This leads me to make the first semantic association that the theme allows for: in this biennial, foreigners are a symbol of transience, displacement and otherness; they come to signify a disruptor, a change in narrative, a harbinger of a time of shift. Pedrosa’s biennial [I started at the Arsenale] walks you through veils of a foreign experience, until it allows the nations and their pavilions to make statements.

The didactic experience of this biennial is immediate; in the sense that there is an overwhelming textural departure from what we have come to expect – something that immediately captures my attention. Whilst the screens, videoworks and projectors that are typically ubiquitous to any art exhibition of this scale do eventually appear, in this year’s central pavilion, textile is first permitted to have its radical moment. Not only is this a clear statement by the curator but also a strong emblematic tool of healing; one that, perhaps, the world, at a time of increasing hostilities, the growth of right-wing movements and surmounting conflict, needs more than ever. After all, textile art is an act of mending; it is a laborious, intensive process which creates irreversible bonds. It requires a deep investment and sensitivity to different materials, to create a united whole.

As the main curator of the Venice Biennale does in every edition, Pedrosa lays artworks of the central pavilion across the two locations – the Arsenale, previously a Venetian shipyard, and the Giardini, a public garden hosting permanently built pavilions. Multifold foreign-ness is exhibited within the spaces of the central pavilion. I like that multiple elements of the archetype are investigated, albeit in different, not always equal, volumes. With Omar Mismar’s ‘Two unidentified lovers in a mirror, 2023’, in mosaic, there is the sense of a renegotiated historicism that this biennial seeks out.

I find significance in the works of Nour Jaouda, Dana Awartani and Anna Zemánková, to name a few. They create and impose woven and textural experiences that are intricate yet simultaneously soothing – solemn, even. I find it fascinating that contemporary art finds itself in close encounters with so much posthumous art in this biennial – whilst Jaouda and Awartni are living artists, the work of Zemánková is being shown after her passing. Not only is Pedrosa ushering in a space for the foreigner today, he is also proposing it as part of a lineage across time. His Nucleo Storico- an archive showcasing work by artists who are no longer alive – does something important. Not only does it elevate voices from Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia – which the whole event aims to celebrate – but also from the Italian diaspora. This, I find interesting because it challenges nationalistic ideologies spreading across the world right now, and Italy in particular.

As I move beyond the central pavilion, I wish to claim, as an aside (albeit on a related note), that I find the idea of a national pavilion to be quite outdated. I think it establishes the very borders that biennials like this year’s in Venice are precisely out to challenge. Thus, it has been a curious experience for me, making my way around each country’s statement. Somehow, most pavilions that occupy spaces in the Arsenale, resonate more than the built ones withinthe Giardini. National and political imbalances in terms of budget, press exposure and attention create, as they always do, a different energy around different national pavilions. The fact that Foreigners Everywhere does not rethink the 1851-style Great Exhibition format of nation-divided representations, to me, feels like a missed opportunity of sorts. For an interest in art at the fringes – where cultures intersect and bleed – the names presented at the front of each pavilion assert a certain dominance which is, at best, a bit passé.

Some pavilions however, rose above and rethought this reality. A particular pavilion that I find to be very intriguing is the Dutch pavilion, which runs in parallel with a live-streamed event in Lusanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Titled ‘The International Celebration of Blasphemy and The Sacred’, it presents, within the Giardini, earth sculptures made from the last remaining patches of untouched forest in Congo. Co-relatedly, the artist collective responsible for the pavilion’s creation, requested the temporary return of Balot – a sculpture made in 1931 – from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to Lusanga. The sculpture was installed within the White Cube, which is a museum built upon the former Unilever plantation after the community reestablished their ownership of it through ritual and spiritual encounter. This sculpture has sacred foundations, protecting the community from the plantain regime – in this sense, the pavilion really emerges as an encounter with beauty, a renegotiation of histories. Whilst it does not erase the story, it reframes it to create a spirit of resolution.

Three other pavilions catch my eye within the Giardini: those of the United Kingdom, the United States and France. Each is experiential in a different way, using moving image, sound and sculpture to create immersive environments. I feel most moved by Ghana-born John Akomfrah’s ‘Listening All Night To The Rain’ for the United Kingdom, which proposes water as a container of memory. The artist, together with curator Tarini Malik, uses film in fascinating ways to invert the geography of the pavilion, taking audiences from the basement up to the higher floors – a kind of spatial poem encapsulating foreign-ness. The work of Jeffrey Gibson for the United States is a feast of colour with statements woven across the site about native cultures whilst the pavilion by Julien Creuzet for France suspends highly tactile works from its ceiling, juxtaposed with striking video works. It feels like a new ecology, a humanless environment, despite the effects of human intervention being continuously alluded to.

At the Arsenale, I am overwhelmed by the power of the first-ever pavilions for Benin and Senegal. ‘Everything Precious Is Fragile’, curated by Azu Nwagbogu, is clever not only in discussing complex notions of postcolonial identity but also because it does so within a critique of the artworld and Venice itself. Chloe Quenum’s ‘L’heure Blue’ recreates a window from Venice’s Arsenale and positions a number of glass sculptures ahead of it, reminding us about Venice’s own complicated past, issues of slavery and the commodification of cultures. Ishola Akpo’s ‘Traces of Queen IV’ sits powerfully alongside it. Franco-Senegalese artist Alioune Diagne creates a large overwhelming painterly work using small calligraphic interventions. He presents a mural featuring scenes in a puzzle-like configuration, humbling in its presence.

Disappointingly, I had to miss out on the Egyptian and German pavilions, the queues for which were just too long for a trip as short as mine. The pavilion of the Holy See is the one I wished to visit most; but its accessibility was limited and spaces fully booked. Having read extensively about the narrative, the location and the curatorial ambition of the Holy See’s project, I might even convince myself to come to Venice again. Securing a visit to this pavilion at a women’s prison on the island of Giudecca sounds like a moving curatorial experience.

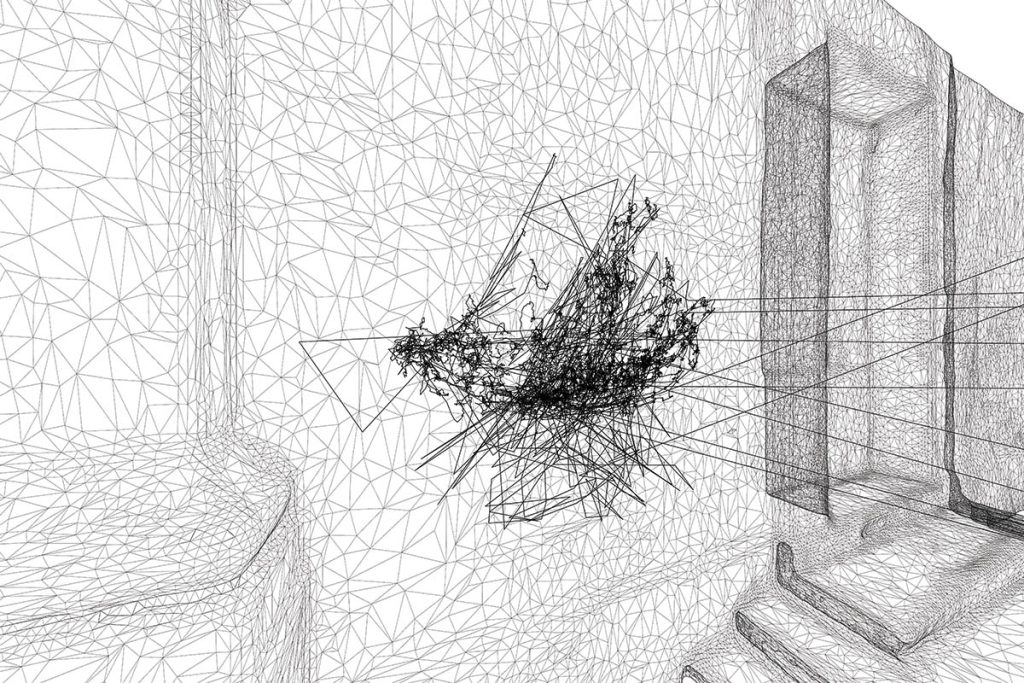

The repeated neon statement ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ in different languages across Claire Fontaine’s titling artwork, which is suspended above the water of the old arsenal, creates this beautifully abstracted puddle of light; blurring the boundaries between different languages completely. The Italian pavilion in the Arsenale ‘Due Qui/To Hear’ – intelligently crossing ‘Two Here’ with ‘To Hear’ – creates an immersive experience and introspective journey through sound and space by artist Massimo Bartolini. In both Fontaine’s and Bartoline’s theses, abstraction holds power. Perhaps what I enjoy most – amongst all the statements of this biennial – are these opportunities for quiet poetry, moments of abstraction and open-endedness that depart from conventional use of language and inspire individual contemplation.

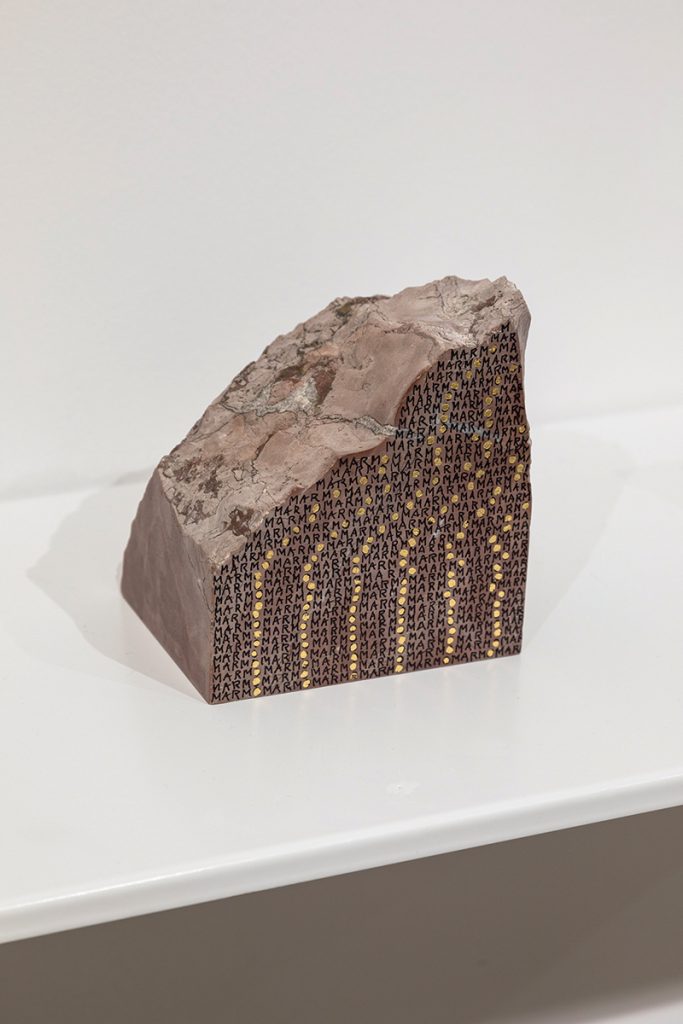

The concept of foreign-ness is an opportunity to transport viewers to another, not necessarily real, place. This poetic fiction is an opportunity to inform our prospective futures, allowing for space for interpretation, intervention and continuous deliberation. I sense this as soon as I see the works by Greta Schödl in the central pavilion. Her ‘Marmo’, written with subtle gold leafing across pieces of raw extracted marble, is a welcome fragment of abstract, visual poetry. It echoes – at least for me – the kind of spirit embedded in the work of artist Matthew Attard within the Maltese Pavilion. ‘I Will Follow the Ship’ has emerged as a winning pavilion on many journalists’ lists and I think it is because it finds poetic licence in the traces of the foreigner. In sharing territory with the eye-tracking device, his work is a negotiation between two real-life foreigners who forge a way through codependence. His work finds agency in this kind of negotiation, and this has been communicated well by Malta’s whole team in Venice. Acknowledging the role of the disruptor, the peripheral, the foreigner in Malta informs us better not only of who we are, but who we are becoming. This acknowledgement feels more urgent currently – something which, I believe, art emerging in the wake of the assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia has an obligation to reckon with. Malta’s pavilion, this year, doesn’t present politically-loaded statements, but rather finds solace in anonymity and poetry. The young, inspiring and talented team strikes a chord in the way it ushers the history of ship graffiti into contemporary idiom. It allows technology not to take over but inform the artist and his audiences. It celebrates the imprint of the anonymous and creates space for them to continue leaving their mark.

Months have passed since the students presented their work at the end of their design workshop borrowing the Venice Biennale’s title, and the world is in only a worse place than it was last October. The absence of two countries in particular reads as an admission of grievances that the artworld is increasingly – although not specifically at this event in Venice – more critical of. An armed Italian guard stands near a closed Israeli pavilion, blocked with a statement calling for a ceasefire. The Russian pavilion – closed once more as the illegal occupation of Ukraine continues – has been borrowed by Bolivia, a country whose lithium resources are of growing interest for global superpowers.

The Venice Biennale becomes a way-finding path to a place that is at once disconcerting, but also hopeful. The artwork seems to chart a new territory, built on old narratives but forging a new way. The everywhere that this biennial speaks of, reconciles with common injustices, discriminations and pasts, but proposes – or at least tries to propose – a new way of contesting them. As foreign-ness continues to rear new heads, we need more opportunities to encounter each other. The current biennial offers one such chance. Whilst not all of it is substantial, the sum of its parts holds an urgent message.

With special thanks to Lily Agius and Maria Theuma.