Venice Architecture Biennale 2021

How will we live together? A most timely question, addressed in an old-fashioned way

.

A traditional opening of the 17th Architecture Biennale seemed improbable up until a few days before the (stereo)typically glamourous crowd of architects, artists, journalists and curators arrived in Venice as they would every May in pre-pandemic times. After months of lockdown, and despite traveling restrictions and curfews, the city was suddenly once again teeming with life and activity. Swarms of visitors sipping on their spritz while indulging in the “high-brow, transitory theme park of ideas for the educated elite,” as defined by Carolyn Smith on The Architectural Review.

Curated by Lebanese architect Hashim Sarkis, Dean of the School of Architecture at the prominent Massachusetts Institute of Technology since 2015, this Biennale had to face great challenges, including being postponed twice and losing participants along the way. But it was also offered an unprecedented opportunity for real, radical change by the global crisis of the status quo.

The main theme, “How will we live together”, was almost prophetically announced a few months before the COVID-19 outbreak, in an effort to assert “the overlooked role of the architect as both cordial convener and custodian of a new spatial contract”. What kind of new spatial contract? One in which “we can generously live together, as human beings, as new households, as emerging communities demanding equity, diversity and inclusion, across political borders and against global crisis”, as Sarkis explained during the inaugural press conference.

Many urgent topics – perhaps too many – have all been exacerbated by the pandemic. Their complexities produced one of the most puzzling, outdated and energy-draining exhibitions that the former rope-making factory’s spectacular spaces have ever hosted. The main exhibition at the Arsenale, in fact, reads more like an anxious amassing of high-tech wizardry, models and materials that one has to patiently sift through, than a real attempt at answering the most relevant central question in a lucid and meaningful way. The main pavilion at the Giardini, also curated by Sarkis, is equally chaotic, but presents a few particularly valuable contributions, with more representations from Latin America, Africa and Asia than usual.

“How will we live together depends on all of us being present in all of our dignity and expressions, thinking and individuality, but also collectivity,” the curator said in an interview with Dezeen, adding that “Biennales past – maybe two generations ago – were about Europe and North America showing the rest of the world where the avant-garde was going, and the rest of the world coming to Venice in order to copy it, while now it’s the whole world coming to show their solutions, their ideas in Venice”. But is it still the case, that in these times of utter crisis people (and enormous quantities of resources with them) should travel across the globe to be able to share ideas?

Sarkis’ vision does not go as far as questioning the legitimacy of the Biennale. On the contrary, it seems primarily preoccupied with covering all the expected main themes, ticking all the boxes and reinforcing the all-encompassing character of the big machine that the Biennale has become. 3D fabricated pavilions and robots standing next to poetic installations speaking of political emergencies and truly sustainable initiatives from remote lands: the intentions are good, as much as their outcome is confusing and frustrating. With no real concern for what the vulnerable city of Venice might need to find a better balance between tourism and locals’ necessities, and very meek efforts to adapt pre-pandemic solutions to the emerging global scenario, this Biennale does not go much beyond its good intentions.

A few national pavilions explore specific aspects of the ambitious curatorial question in original and stimulating ways, whilst some unofficial collateral tackles hot topics like the extractive nature of architecture (VAC Foundation); or the bizarre case of the unknown replica of a John Hejduk’s project on a Venetian island, demolished in December 2020 to make way for a glamping site and taken as a case study of contemporary solitary domestic dynamics (Unfolding Pavilion). Also, among the official collateral events, the European Cultural Centre hosts AKKA, an installation about reconstituted stone by the Maltese studio, A Collective, in collaboration with the University of Malta, photographer Julian Vassallo and James Vernon.

Highlights – at the Arsenale

From the main exhibition curated by H. Sarkis:

- OMA / Reinier de Graaf’s short film Hospital of the Future, Corderie

Will hospitals be able to operate remotely? How? If the number of global patients keeps increasing, how will the system cope with the increased demand for medicination? Who produces it, how and where? How sustainable is it? Reinier De Graaf’s contribution is a series of crucial questions and speculations about how health care structures will evolve, mainly in relation to demographic changes and technological progress – and a much welcomed comfortable break at the end of the chaotic Corderie’s exhibition.

- Doxiadis+, Entangled Kingdoms, Corderie

A “glowing fungal garden” grown from fungal spores collected in situ, propagated in the mycology department of Athens University under different conditions, “until a result was reached which would show the beauty of what is around us but we do not see”.

- Gabriela Bila Advincula, Kent Larson,MIT, With(in): Three women, three informal settlements, and the rituals of the meal as a microcosm of urban life, Artiglierie

An immersive video installation following three women in their daily routines, in three different parts of the world and, in doing so, exploring a very humane research methodology aiming at understanding communities and urban specificities through table and food rituals.

- Elementals installation, at the end of Artiglierie, overlooking the Gaggiandre

The spectacular installation designed by Alejandro Aravena’s team tackles the recently increased violence in the historical Mapuche-Chilean conflict. A wooden structure evokes the traditional spaces that used to be built for parleys, in order to settle differences and discuss terms for an armistice, while informing visitors with documents and images of the conflict. What better space than the outdoor area overlooking the old venetian dockyards for a moment of contemplation and, perhaps, even a serious attempt at imagining how we might live together?

National pavilions:

- Mahallas, Uzbekistan, Artiglierie

The Uzbek debut at the Architecture Biennale with an installation by Carlos Casas and 12 photographs by Bas Princen, among other works,is a glorious abstraction of Tashkent’s historical urban neighborhoods, called ‘mahallas’, and their vernacular courtyard houses. The pavilion reads like a three-dimensional collage that explores the value of ancient forms of urban community life in a direct – perhaps at times too direct – but limpid way.

- Wetlands, United Arab Emirates, Sale d’Armi

Curators Wael Al Awar and Kenichi Teramoto took Sarkis’ question to the next level: how will we survive together? Their answer is a fascinating and resourceful attempt at creating local resilient supply chains for the construction industry (responsible for majority of the country’s pollution), by turning to nature. The exhibition presents the results of an extensive research on an alternative cement mixture made of natural materials like minerals, salt and sand, abundant in the Emirates and many other Mediterranean countries – including Malta, where the need to develop ad-hoc strategies to react to climate crisis phenomena like desertification is now more urgent than ever but unfortunately still overlooked and oversimplified.

Highlights – at the Giardini

From the main exhibition curated by H. Sarkis:

- DAAR, Stateless Heritage; All purpose, AAU Anastas; FAST, Border ecologies and the Gaza strip.

Several projects addressing the question “how we will live together – across borders” face issues of recognition and identity but also show opportunities for contemporary reinterpretations of vernacular building techniques and innovative uses of traditional materials in border areas. The most relevant contributions come from the Palestinian region: DAAR, with a provocative film in which they challenge the Western-European approach to heritage and culture, AAU Anastas, with an experimental stone structure inspired by ancient masonry traditions from the Bethelem area, and FAST, with an installation attesting the indefatigable resistance and solidarity of the small rural Qudaih community, in one of the most unstable and violent Gaza strip territories.

National pavilions

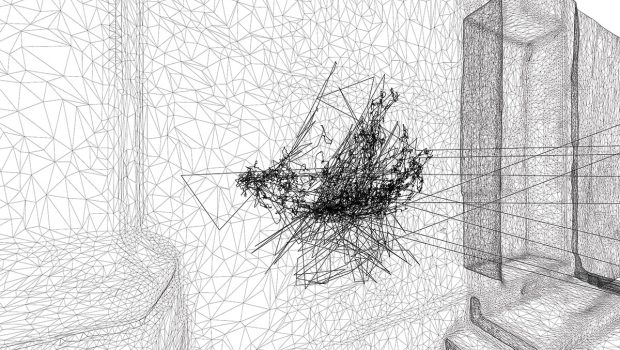

We Like – Platform Austria, Austria

Curated by Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer, the Austrian pavilion “seeks to articulate the profound changes established by the development of digital platforms in our built environment”, as they write in their opening statement. Solid with all the right political and historical references, the pavilion is a brilliant succession of thought-provoking and digital-platform-reminiscing images and quotes, from Marx to Cardi B. “Access is the new capital” and “Data is a relation not a property” are just two of several curatorial statements resonating with Jenny Holzer’s truisms and their radically critical spirit.

The Garden of Privatised Delights, U.K.

Manijeh Verghese and Madeleine Kessler elevated the crucial role that public spaces will have in the visions of “how we will live together” to the central tenet of their narrative. With a playful and suspiciously Instagram-friendly exhibition design, they question the diversity, inclusivity and accessibility of most British cities and the cultural roots of their extreme liberalism.

Co-ownership of Action – Trajectories of Elements, Japan

The project curated by Kadowaki Kozo is a delicate exercise in re-considering construction waste as a potential precious resource, and in questioning mass consumption dynamics while doing so. Elements from an ordinary Japanese wooden house, laying on the floors like pieces of a dissected ancient presence there for us to learn from, remind us that “our actions are not ours alone. Any act, however trivial, sits atop an accumulation of countless acts that arose from our interactions with someone else. Therefore it can never be said that what you do belongs solely to you.”

Highlights – Biennale’s Collateral Events

- A Collective, Akka – part of ‘Time Space Existence’, at Palazzo Mora

On a different planet, revolving around the same curatorial theme of ‘Time Space Existence’ since 2014, the exhibition organised by the European Cultural Centre includes Akka, an installation by Maltese architects A Collective showcasing the work of videographer James Vernon and photographer Julian Vassallo – very much in line with the debate at the Biennale, in spite of the exhibition’s main title. Akka reflects on the urgent need for sustainable alternatives to current construction methods and materials; reconstituted limestone, currently being developed by the University of Malta, is taken as an example of “intrinsically local, recycled material” and a potential building material of the (near) future.