A Forced Marriage

How do you shake conservative people into taking contemporary art into consideration? How do you explain that an artist is a purveyor of thoughts and not a copier of nature? A forced marriage, obviously.

At prima facie they seem to accept each other.

Perhaps one day they will respect each other.

Perhaps one day they will learn to love each other.

And from the outside, the beautiful venue that hosted The APS Mdina Cathedral Contemporary Art Biennale 2017-2018: The Mediterranean: A Sea of Conflicting Spiritualities, looks as if it was built for the purpose of hosting this unlikely marriage. The two statues on either side of the entrance, holding up the portico roof, are forever close but never touching – just as the church would want it.

The biennale is a themed show, but one which also offers a blank canvas for the artists to come up with some space-related and some site-specific works. It is one of the few opportunities for Malta-based artists to exhibit shoulder-to-shoulder with contemporary artists from other countries and realms and, under the artistic direction of Dr Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci and with the curating talents of Nikki Petroni, I would say it is generally an impressive success.

But how does one go about proposing this marriage? How does one have some 30 or so international artists having a conceptual discussion about ‘Politics’ and ‘Identity’ with their chosen space – the museum of ancient religious treasures – the museum that makes artefacts of both the tools with which to conjure up amazement and awe and the ones with which to inflict oppression? The figurative husband?

Whenever the church perceives a cultural threat, it makes sure that the young virgin marries the big, old-fashioned church – perhaps in the hope that she will understand what her husband believes to be the underlying answers to every question the universe poses. The Catholic Church is obsessed with marriage – with forcing the interweaving of one complex tapestry onto another, promising that the result will be a blessed holy union capable of finding answers to every possible issue and situation, with the help of the almighty God.

The Mdina Contemporary Art Biennale is an incredible showcase in which a neatly curated collection of pieces is incredibly superimposed onto an already rich array of treasures and masterpieces. It is almost as if the hosts are telling us that it is ok to think progressively, as long as every little bit of dogma is still respected and looked after – a task requiring a near impossible amount of effort. The effort starts with trying to visually concentrate on the works in some of the spaces, some of which are beautifully paired with the baroque and mediaeval props and relics which often, in this exhibition, go from being seen as priceless objects to lowly means of support for paintings, artefacts and other components of the installations.

One of the best-paired sets of works was the photographic diptychs by Malta-based Serbian artist Duška Malešević. Obsessed with shadows, she presented two pieces of contemporary urban photography with minimalist angles and a strong anthropological line of questioning. Perhaps some of the other works belonging to the Museum’s permanent collection in the same room could do with the casting of some of her shadows of perspective. If only Düska had discovered her eye earlier, say 25 years ago, imagine what wonders and discoveries hidden in plain sight she would have uncovered for our eyes to see before whatever they represented rotted away to the level of charm that caught her eye.

In these upstairs halls you cannot help but wonder: can an atheist have a good relationship with an unquestioning believer? Where do their minds meet? How sharp is that line or how blurred? Can they truly be honest with each other? These questions were raised by the Golden painting by Guy Ferrer and his ‘man’ seemingly begging for an injection of spirituality, and in the imposing work by Darren Tanti. Tanti’s work is a fresh-faced strong image which is both dominating and yet shining pastel hues on everything beneath it. On a side note, it was quite interesting to find out that part of the image had been hacked off in an act of blatant censorship when the Biennale was reviewed on our national airline’s in-flight magazine prior to the show’s opening. Yet here it was: the virgin, which is contemporary art, being paraded amongst the elders.

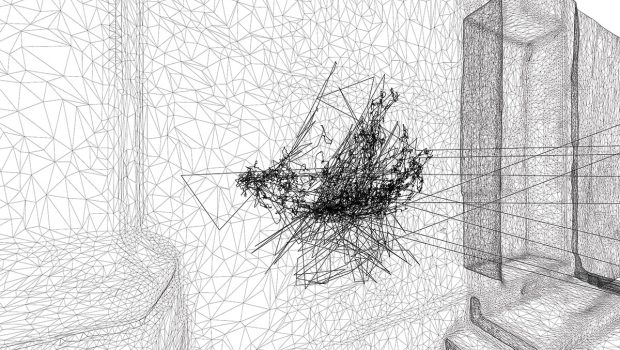

Another beautiful work trying hard to find its place amongst the paintings of the Old Masters as they hang in layers upon layers of the dust and dirt of time was the layered relief by Vincent Côme. As he writes himself, his work is about: ‘Glissements, enchevêtrements, mélanges, croisements, intersections, compilations, confrontations, entrechoquements, fusions, frottements,… strata, ħrieqi, stacks, suppositions, munzelli, irkupri, taħbiliet, akkumulazzjonijiet, spostament, il-migrazzjoni… konverżjonijiet u l-konverżjonijiet… Layers, layers, stacking, intersections, compilations, confrontations, clashes, frictions…’

Underground

In the basement, deep underground, ancient Byzantine remains were lit up by British artist James Alec Hardy in a site-specific installation that was painfully hard to experience, making that experience, in fact, one of fascinating frustration. Hardy’s installation was reminiscent of the mythical burning bush, or the promised light at the end of the tunnel of one’s life, and yet this cacophony of lights was generated by diodes in old PCs and not by the supreme being. Perhaps the last time these rocks had seen the light it was in fact generated by God himself.

Thomas C. Chung is telling the metropolitan chapter and all of its visitors that ‘We Are Not All Gods’ with an installation of crucified knitted superhero plush toys. Perhaps a superhero requires crucifixion by her or his community in order to finally be taken seriously – in order for them to finally believe in her or him.

Courtyard

I had already seen part of Clint Calleja’s installation presented as part of his dissertation for the Masters Degree in Fine Arts offered at the University of Malta – or rather images of it in Strait Street, as the boat-shaped sculpture was at the Addolorata Cemetery. It also took me back to a visually similar installation by Norbert Attard, although Calleja’s work has the addition of the names of several fallen Maltese on its side. My thoughts at his dissertation presentation flew to the fact that we assign so much value to our locally departed, and yet have become desensitised to the overwhelming numbers of asylum-seekers drowning as we eat, speak and sleep. This time around, the sublime wooden sea vessel is seen crashing into and destroying a shoddy excuse for a boat inscribed with numbers.

‘Who the hell are we?’ to continue to be obsessed with our identity while conveniently forgetting the plights of the world when we are conceptualising our work as artists? (I imagine they should be thinking.) Michael Von Cube goes political in his cross-era, cross-country, depressingly and yet playfully tongue-in-cheek paintings as he guides us to the imposing halls upstairs.

Front rooms

One of the most visually stunning rooms was the one with the incredible Hania Farrell domed prints of collages of photos featuring the underside of beautiful baroque and mediaeval church domes and their masterpiece paintings.

Hania Farrell was born in Lebanon and now lives and works in London. Images of her works were the most featured in press releases and features of the biennale in the media. She gives us an ‘underneath’ kind of view of the power of the church’s architecture as a tool of awe-driven dominion on humanity through the ages. A question into ‘what’s beneath it all’; a view of (delusions of) grandeur which one can appreciate without having to kneel down and look up. Farell’s work also obviously reminds us of the sheer magnificent beauty we have inherited in the form of religious art, and perhaps highlights the fact that liberal, individualistic, secular societies are choosing to attribute less and less value to these church-sponsored elements of culture.

Are we deliberately allowing old relics of faith to decay? Are we waiting until they decay enough physically to catch up with the decay of spirituality? Why do we restore religious relics? What happens to their meaning, their value when they are being increasingly overshadowed by contemporary icons? Does anyone care if they are overshadowed to the point where they do not matter anymore? And what is the cut-off point for respect? Does the contemporary artist allow her or himself to pay credit to the modernists, for instance?

The modernist pieces by Barthet and Portelli were perhaps envisaged as the main magnetic pull of the show for the more conservative members of the potential audience. Personally, I think they took far from a central stage position which augurs well for the Maltese emerging-and-getting-there contemporary artist. However, conservative or not, any visitor to the Mdina Cathedral Museum in December or early January certainly got more than they bargained for, more value for money, more food for thought – if only there had been a free public version of the catalogue to guide the casual visitor through the maze of artists and works, as the main catalogue – although exceptionally put together – was beyond the scope of these visitors: the wedding-crasher sort of visitor, who knows neither the bride nor the groom.

The church has always been a staunch supporter of marriage – whether the marriage was likely to be successful or not. It is usually pleased as long as the couple stays together. As an institution, it would usually rather not be aware of or deny any misbehaviour or – even worse – abuse by one of the couple towards the other. In this marriage, however, the space forced the criticism to the surface, and shone a light on it. Whether or not the light was strong enough for the rebellion of the contemporary to be evident is something only the individual can conclude on a visitor-by-visitor basis.

The APS Mdina Cathedral Contemporary Art Biennale 2017/2018: The Mediterranean: A Sea of Conflicting Spiritualities, was organised by curator Nikki Petroni and Artistic Director Dr Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci. Participating artists hailed from Australia, Austria, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Israel, Jordan, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Russia, Serbia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. A catalogue of the exhibits, which includes essays by scholars and curators, has been published by Horizons and can be purchased from local bookshops.