All Too Human Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life

Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life

As the 20th century progressed, the depiction of the human figure in western painting inevitably captured something of the turmoil of a society amidst the horrors of two world wars and the existential crisis engendered by the development of nuclear weapons. Whether this was by design, or simply due to the fact that we naturally seem to relate to images of the body and endow them with emotion more easily, is sometimes hard to discern.

The exhibition All Too Human, which is running at Tate Britain until 27th August, posits a much more insular vision of modern figurative painting in Britain, particularly London, from the turn of the century to the present day. The show also presents a number of prominent contemporary artists as a sort of coda to a tradition of figurative painting over a century long.

Jenny Saville, for example, is represented by an impactful image of a seemingly battered woman’s face in extreme close-up, rendering each gleam of light and strand of hair into an expressive abstraction. This is most evident as one moves away from the canvas, and the subject only comes together as a recognisable image with distance. Saville engages the viewer in a kind of dance between the presented image and the painterly surface, her monumentally large canvas demanding your attention by amplifying the face into a sort of corporeal landscape where every protuberance becomes an alien landmark for your eye to catch upon.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is another recent painter of note, providing a much-needed update of the black body in western figurative painting, spotlighting figures which, for far too long, only existed on the periphery of artistic tradition. One cannot help but connect the subjects of Yiadom-Boakye’s lyrical paintings to the tragic news stories that we hear all too often of politicised and racially-motivated violence. However, the artist’s elegantly painted subjects do not come across as nameless victims but as self-contained individuals. They are as lucidly painted as any Singer Sargent portrait, with a gritty contemporary edge to boot.

It is Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, however, that curator Elena Crippa chooses to position front and centre as the predominant painters of the human figure from this time.

Once close friends and providing an important influence on one another, Bacon and Freud eventually had some sort of falling out that left them locked in a bitter feud. Freud, with characteristic meanness, refused to ever lend Bacon’s 1953 masterpiece Two Figures, which he owned,to any exhibition. This especially dismayed Bacon who was rightfully proud of that important work depicting two men locked in a sexual embrace, frank and unapologetic. Produced in a society in which homosexuality was still a punishable crime, it was decades ahead of its time and should have been seen publicly much earlier than Freud’s sense of rivalry would allow.

Bacon’s stylistic iconography – those empty, haunted spaces and contorted fleshy masses – lingers on in the work of younger painters, including artists such as Cecily Brown. Brown emulates a similarly painterly approach in deconstructing the human figure, and especially in displaying bodies coupled in some sort of sexual union. She does so in a way at once obscured by corporeal swathes of paint and yet still somehow candid to the point of pornographic. She makes the viewer feel complicit in some guilt-inducing act – for example, by placing us in the position of some dirty-minded voyeur spying on coupling lovers in the park (Teenage Wildlife, 2003).

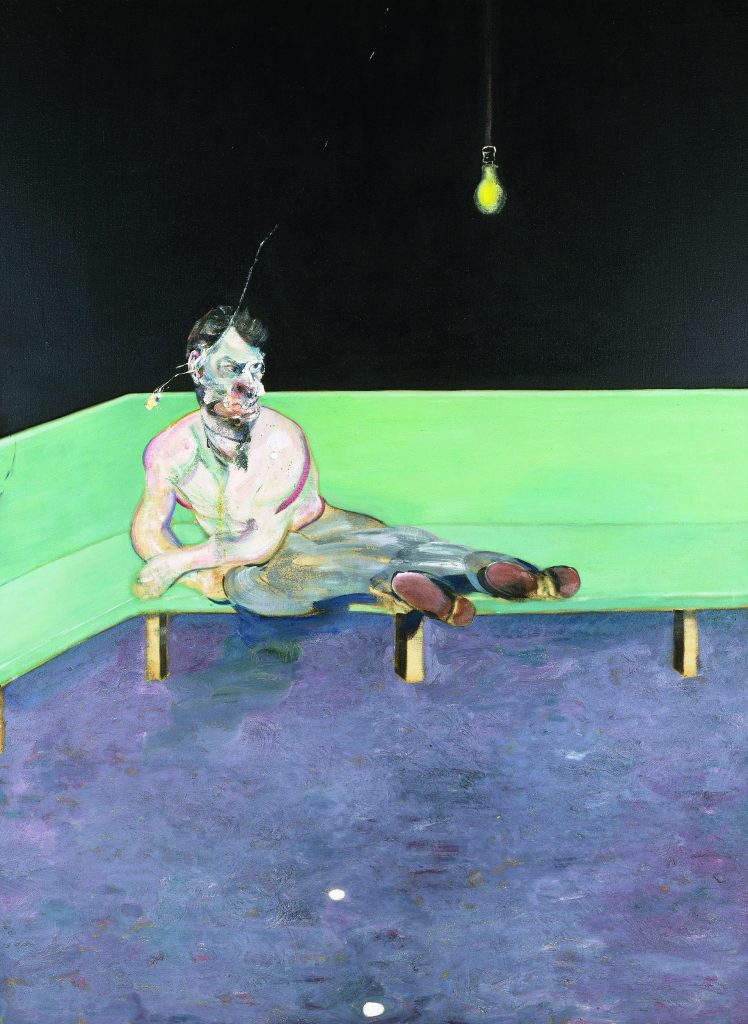

One does not sense any similar shame in Bacon’s work, all the more remarkable given the sense of depravity that his horse-breeding father must have imparted upon him as a gay adolescent, bullying his son with cruel physical punishments that, by his own admission, played no small part in his tendency to masochistically chase violent older men as lovers.

Bacon recalibrates the trauma of his youth to craft his own unique world view, distilling a sparse and unwieldy beauty out of raw pain and isolation. One never senses the artist claiming any sort of moral stake in what he posits is an emphatically amoral world – placing Bacon much closer to the sentiments of the Parisian Existentialists than the rather staid pontifications of many of his compatriots (and indeed, Bacon was appreciated and celebrated in France far more than on home ground, at least for most of his lifetime). This is further underscored by the presence of one of Alberto Giacometti’s cadaverous bronze figures, encapsulating the haunting sense of loss felt just after the end of the war, as the victims of the Holocaust were still being uncovered in camps across Europe.

There is, nonetheless, a yearning for human connection in Bacon’s later paintings. One of his greatest triptychs (Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer from 1971, not included in this exhibition) depicts the suicide of the artist’s lover George Dyer, slumped over dead at the bathroom sink (a classic Baconian merging of the banal and the terrible.) In the adjacent panel, a proxy for the artist himself turns to lock the door to his studio building, glancing back mournfully towards the empty room where a single light-bulb glows poignantly, illuminating the hallowed space with an ephemeral gleam.

Crippa culled the name for her show from a particularly existentially-charged line from Friedrich Nietzche’s book of aphorisms “Everywhere he looked… what he saw was not only far from divine but all-too-human.”

This phrase could very well have been written about Lucian Freud. Students of the artist’s grandfather Sigmund might have a field day with the unflinching nude portraits of the artist’s own daughters, or the naked lovers apparently basking in a post-coital haze next to his elderly, buttoned-up mother, yet Freud resisted such psychoanalytical readings by viewing human beings simply as animals to be observed in mind and in body, more objects of biological study than psychological analysis.

An Austrian-German Jew (though later naturalised British citizen), his family fled Austria during Hitler’s rise and their exile in Britain was facilitated through Sigmund’s aristocratic associations. Freud always felt something of an outsider, and, although not an observant Jew, he spoke of encountering anti-Semitism in his adopted homeland, where his beloved cabbies would regularly complain about those “bloody saucepans” (saucepan lids – yids.)

Through talent, charisma, guile and connections, he was able to integrate himself within the upper echelons of society, but one never stops feeling that Freud was only able to relate to other people as subjects through the act of painting. Slowly he picked away the psyche of his sitters to reveal their emotional core just as his storied grandfather must have spent countless hours coaxing out his own clients’ deepest secrets, fears and desires.

An early painting included in this show is his closely observed still-life of a squid and sea-urchin, betraying the artist’s enduring obsession with capturing the fleshy surface of his subjects in unremitting detail. Its dimensions are modest, amplifying the intensity of the artist’s vision and it is a small miracle of a painting.

Freud produced some of his most emotionally affecting work when portraying those to whom he was most keenly connected – such as his first wife, Kitty Garman, who he depicted with icy accuracy almost strangling a kitten in her fraught embrace (Girl with a Kitten, 1947). This telling portrait is both tender and yet undercut with such an uneasy sense of violence simply waiting to erupt.

In another, much larger, canvas, she crouches on a sofa staring out as if transfixed by the viewer’s entrance, a white pit bull terrier (one of a pair the newly-married couple received as wedding presents) resting its immaculately rendered snout on her leg, her similarly pale breast escaping the confines of her gown. It is an electrically charged, bizarre picture. Kitty’s eyes are glassy, as if filled with tears for having been kept open so long. She wears a slim gold band on her finger, a wedding ring, but this marriage was not destined to last much longer –another victim of Freud’s chronic philandering.

What to say of the other artists featured in this show? Well, due to space constraints and at the risk of sounding glib, I will provide a very brief summary. I am not a huge fan of Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossof’s often stodgily painted canvases depicting mainly London street views and portraits, although I realise that there is something of an undeniable spectacle in the thickly layered paint that protrudes in an almost sculptural manner in the work of both artists.

John Deakin’s photographs are included mainly to highlight Bacon’s painterly process, working from and incorporating photographic images. Stanley Spencer’s naked portraits of his second wife Patricia are charged with an unsettling intensity that somewhat anticipates Freud’s inward-looking worldview, and Walter Sickert’s impressionistic views of everyday Camden Town life and sex-workers provides a fascinating insight into the relationship between painting and photography at the turn of the century.

With all this painterly grandstanding and male gazing at prone, naked female bodies, it is something of a relief to come across the work of Paula Rego, who leads the viewer through her carnival-like reinterpretations of Portuguese folk tales, where social status and scale are readily inverted and seem to have little bearing on the rules of her world. Aged crones are infantilised, left bereft of their senses, while animals and inanimate objects are given a spooky cognizance.

Rego places women resolutely at the heart of her work and by so doing readjusts the idea of art as a historically male-dominated activity in which women are often side-lined. Here women are portrayed as undertaking a variety of activities, as victims, culprits, carers, passive observers and sexually-charged creatures. Her pastel-on-paper works, usually copied after live models posing in the studio, thereby capture her own desires and fears, allowing the artist to confront personal memories. In spite of the abuse they endure, Rego imparts her women with a sense of determination. They often seem to be colluding together against their male oppressors, as if to regain control of their own narratives.

If any criticism is to be made of this entirely respectable and handsomely mounted show, it might be that it plays things a little bit safe in a curatorial capacity. It is an unfortunate reality that some sort of commercial pandering is often necessary to keep big-brand institutions such as the Tate operating effectively, but this often means that exposing lesser-known artists has to give way to showcasing well-known and therefore profitable names.

There has already been one comprehensive Lucian Freud exhibition in very recent memory and no end of Francis Bacon displays across a number of museums, publications and even television documentaries. Reinforcing the mythologising aspects of these ‘Great British Artists’ does feel somewhat insular and self-congratulatory – stoking nationalistic sentiments for a Brexit-era audience keen to be reassured of Britain’s lasting cultural relevance.

For such reasons, curators and scholars often end up failing to properly interrogate the edified system of patriarchal power and capitalist endorsement that underlines artistic validation and success through museum shows. This is a shame, as doing so will not discredit the creative voice of the artists involved – indeed, it will place their work in a new light and allow us to understand the social and cultural context of its time.

Crippa does remedy this somewhat by ensuring a female perspective is provided in the work of Saville, Rego, Brown and Yiadom-Boakye, but this feels shoehorned in as a kind of curatorial afterthought. Only Rego is afforded an entire room to herself, while the other three disparate artists are placed somewhat awkwardly together in the last gallery of the exhibition. Meanwhile, the more problematic notions of the female nude as seen through the male gaze, which brings up all sort of queasy connotations today, is politely ignored.

Ultimately, however, this show does manage to raise a compelling and persuasive argument for the deceptively simple act of looking at the human figure, both as a way of gauging the development of modern British painting and as a source of beauty and inspiration in its most immediate and engaging form, and it is therefore unfair to judge the curatorial decisions on any other basis.

Seeing the huge crowd gathered to enjoy this exhibition, and subsequently wandering through the rest of Tate Britain’s collections, only made me hope that large institutions such as the Tate choose to vary their programme to further include as diverse a variety of artists and ideas, outside those well-established names on which they could be sure to hedge their bets commercially. I am convinced that doing so will only encourage members of the public to visit the museum time and time again, to enjoy the thrill of the new and the familiar alike.