Two places, two truths

Anna Calleja’s HOMEBOUND at the Malta Society of Arts.

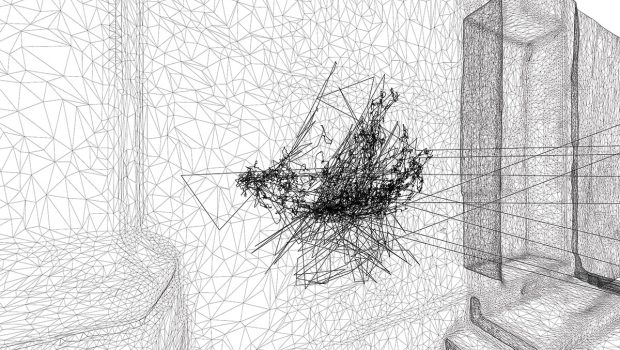

A pair of scissors inhabits the centre of an otherwise blank page. Unassuming, naive, and also a little spindly, the simplicity of the picture belies its hidden depth. This only emerges upon second glance and contemplation. Embedded in the fragile image is another, deeper kind of fragility; the humankind stemming from being caught at the intersection of opposing forces. The scissors on the page look like your mother’s scissors. The rusty pair from the old sewing box that has always sat in the bathroom cupboard under the sink. But at the same time, there’s something archetypal about the image. The object on the page looks as if it has emerged out of stone, from under the sea, encrusted with rust and with memory. Are they even scissors? Perhaps they’re the shears which, as per Greek mythology, Morta, the deadliest of the three Fates, uses in order to sever the thread of life.

In actuality they are both, Anna Calleja, the author of this image tells me. Calleja uses her own internal reality as the axis around which she piles oblique allusions to mythology and the history of art in order to create images that are loaded with meaning that goes beyond the obvious. “I use the micro to understand the macro,”Calleja tells me,“with the scissors, for example, there’s an aesthetic element about a cut, and the scissors being this violent accessory which we use every day, but they have also been painted many times by Richard Diebencorn, an artist I really admire, and in mythology they’re the shears of the three Fates, which are used to cut the thread of life. My scissors are all these things, and by pairing them with another image of my feet on the bed – where I was also thinking of many references, Mantegna, The Lamentation of the Dead Christ, cursed sleep – it creates a kind of narrative. These aren’t things which you think about before the creation of the image, they come after, these little hints at ideas.”

Above images: Anna Calleja, Scissors, monoprint on paper 2020. And Anna Calleja, Fate, oil on panel 2020

Calleja’s Homebound show consists of 43 oil paintings, monotype prints and bronze sculptures that were created during the past 18 months. The works are simple, the compositions uncluttered and the palette generally muted, tending towards the cooler end of the colour spectrum, however the feeling that emanates from them is anything but. The immense calm and the quiet melancholia are offset by an incredible tension. Calleja affirms the intentionality of this; “the themes in my work are very varied, there are positives and negatives and it’s very binary, it’s not all depressing or all good, it’s a way for me to channel thoughts and ideas and narratives and meaning. All the creative things I do are ways of ordering chaos, and mending anxieties through making. It’s a method of sorting through ideas and slowing things down.”

Calleja’s method of exploring the world operates via setting up binaries within her work. The dualities – stillness vs anxiety, closeness vs distance, longing vs belonging etc. – which are created within and between her images allow for the reflection of a hidden dimension in our often subtly contradictory experience of reality. Just as sleep can mean both rest and death, so too do our ideas of comfort contain a kernel of destruction. Incredibly deep relationships, both with places and spaces, as well as those we build with other people, open the possibility for a tremendous amount of love and comfort, but at the same time invite the most keenly felt species of pain. Heartbreak, as defined by the poet David Whyte “[i]s unpreventable; the natural outcome of caring for people and things over which we have no control, of holding in our affections those who inevitably move beyond our line of sight.”[1]

Humankind’s experience in the world is defined via the contradictory logic which is embedded into the manner in which we think and feel. In his 1957 A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, the psychologist Leon Festinger developed a language that enabled the articulation of this tensile dimension of being-in-the-world. As per Festinger’s theory, cognitive dissonance occurs when two clashing ideas coexist in the mind of one individual. Anxiety is resultant from any action that contradicts an already held belief and that disturbs the natural inclination towards conceptual consistency across the motivating force behind conscious acts.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which is very present in Calleja’s work, brought the parallels between comfort and pain starkly to the forefront of consideration as homes became prisons and mandatory quarantine turned ‘solitudinous’ spaces into ‘isolationary’ experiences. “The concept of cognitive dissonance was a good way to go in terms of my research,”she tells me, “because it explains this contradiction of living between two truths. The body of work started before COVID, and always embodied both a distance and a closeness from Malta and my family here. Wherever I was at that point in time, when I was living away, I could never be properly present, because a part of me was always somewhere else. I paint a lot of FaceTime images and video-calls, digital screens, and tech things, and that captures this liminal place between spaces. It was extremely painful, feeling as if my own self was torn in two… between two places, two truths and this limbo in between.”

Using the experience of cognitive dissonance as her starting point, Calleja extrapolates the logic of dual effect outwards and generalises this opposition between comfort and its effects. The Homebound collection also outlines, subtly, the links between comfort and the widespread destruction of the environment. “Sleep was a real metaphor for this, throughout the work, and stillness too. Because sleep is this in-between state, in-between being awake and being dead, almost, and between the past and the future as well. It carries all these connotations, passivity, political passivity, self-imposed blindness, escaping the present, not dealing with what we have to deal with etc. There are lots of sleeping animals in my work. There’s a dog asleep, there’s a cat asleep, house pets are funny that way. The world outside could be on fire and the sleeping cat wouldn’t even notice. But we’re all in that position right now…”

The concept of environmental destruction is an archaic one. Human beings have worked to distance themselves from the harsh realities of life in the state of nature ever since they acquired the ability to create tools. At some undefined point in the past, a tipping point of sustainability was reached, and our development began to loop into a destructive spiral. The acquisition of material and psychological comforts feed into this process and our comforts are created and consumed to the detriment of the planet as a whole.

“So then cognitive dissonance becomes the best way to understand these tensions,”Calleja explains, “and also brings together the macro and the micro. Personal comforts accumulate into large-scale global changes. So the global issues which affect me and cause anxiety and melancholia in the work are definitely part of the reason why I make work and why the work is the way it is. On a global level, our comforts are destroying the planet, completely. Everything from buying food to buying sweets for your kids, buying clothes, going to the cinema, getting into your car… Individual comforts lead to selfishness, lead to extreme capitalism, lead to people thinking individualistically during COVID… lead to every single problem.”

Calleja’s images, however, don’t aspire to be didactic by presenting one perspective or moral maxim above all others. Instead, the works remain ambiguous, and rather elusive, thus allowing the experience of the viewer to set them resonating at a frequency particular to the experiences that are brought into the aesthetic moment. “Well, I think I know that people aren’t going to go in and understand exactly what I was thinking about when I was making them,”Calleja says, “They’re going to bring their own experience to the work, which I like, and hopefully the familiarity will draw people in and they will feel a sense of truth.”

In the words of Anglo-German author WG Sebald, talking about the failings of the novel and 20th century realism in general, “[t]he more obvious you make a symbol in a text, the less genuine, as it were, it becomes […] You just try and set up certain reverberations […] and the whole acquires significance that it might not otherwise have.”[2]

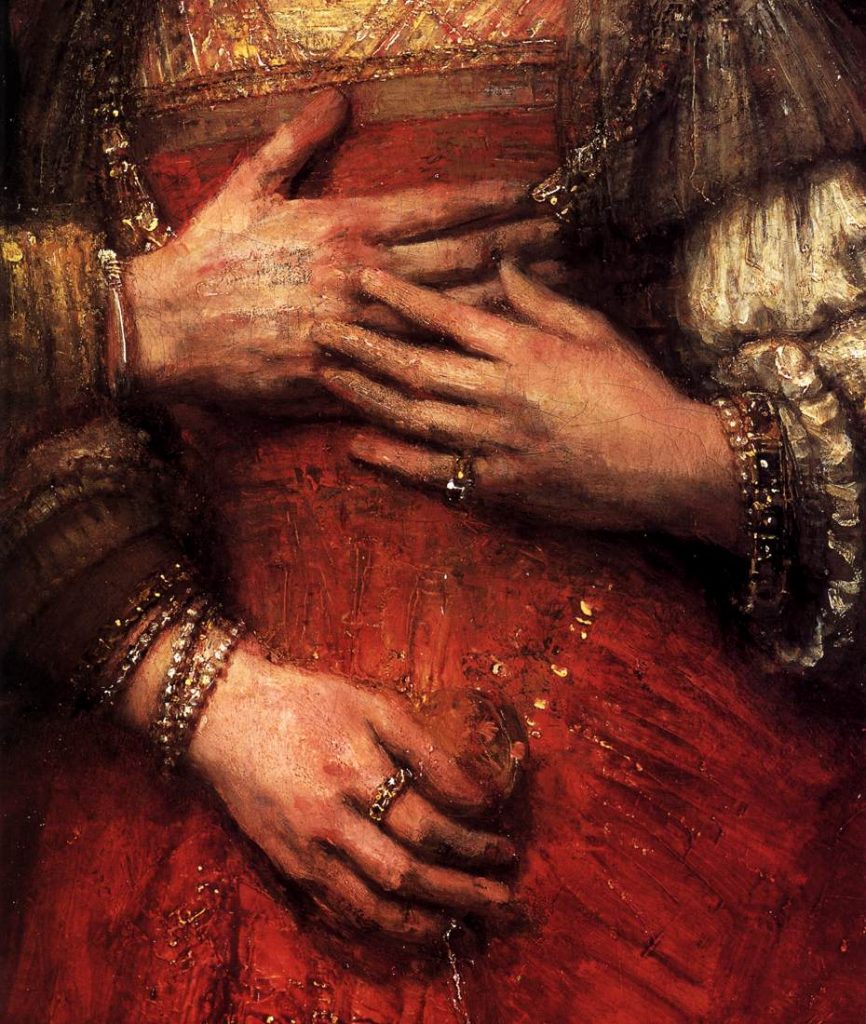

Calleja’s symbols are not obvious. A hand trembles with the same life that can be felt in the hands painted by Rembrandt, an artist who was working in equally bleak times and also suffered from depression and anxiety.

Above two images: Detail from Anna Calleja, Safe, oil on canvas 2020 And Detail from Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride, oil on canvas c. 1665 – 1669.

“[I]n Rembrandt’s great portraits,” writes Ernst Gombrich, “we feel face to face with real people, we sense their warmth, their need for sympathy and also their loneliness and their suffering.”[3] At its most basic, the hidden text suffused into the collection of sculptures, prints and paintings exhibited in Homebound follows along the same lines of Gombrich’s reading of Rembrandt. Where there is comfort there is pain and destruction, and love becomes most clearly itself via a process that also wounds. However, it seems to me that both Rembrandt and Calleja are also telling us, each in their own way, that where there is suffering there is the possibility for reconciliation, and where there is loneliness there is the possibility for a deeper kind of company, and the subtle ache of melancholia can apotheose into something greater than the sum of its parts. To quote Whyte one last time, “Heartbreak is an indication of our sincerity [… L]oneliness is the substrate and foundation of belonging, [and p]ain is the doorway to the here and now. [It] is a form of alertness and particularity; pain is a way in.”[4]

[1] David Whyte, Consolations (Washington: Many Rivers Press, 2015), p. 101

[2] Sebald, as quoted by Eleanor Wachtel, ‘Ghost Hunter’, in The Emergence of Memory, ed. by Lynne Sharon Schwartz (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2007), pp. 37-61 (p. 80).

[3] Ernst Gombrich, The Story of Art (New York: Phaidon, 2006), p. 352.

[4] Whyte, Consolations, 101, 132, 155.