The Victor Pasmore Gallery

Where Saudade meets abstract art

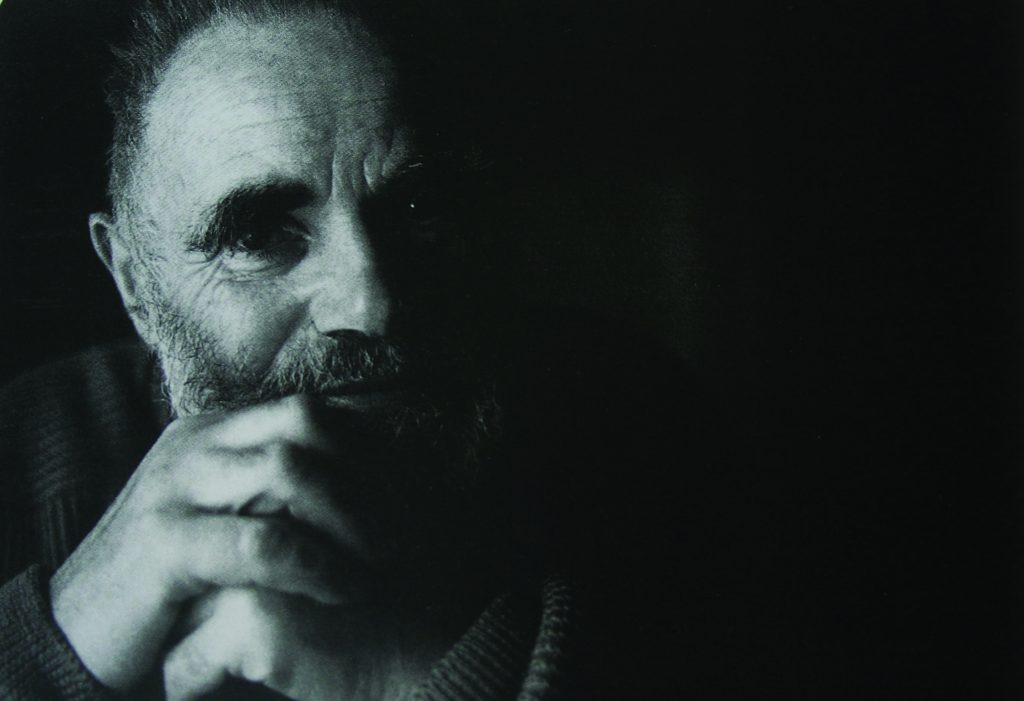

Saudade is one of those elusive, potent words that, try as you might, cannot be translated or accurately understood in any other language if not the original, that is, in Portuguese or Galician. Tentatively, it refers to melancholic nostalgia – an engagement with the past, while paradoxically acknowledging that it is a past which can no longer be engaged with. It refers, more precisely, to the emotive depth of this inescapable sense of loss, which traps one between a dichotomy of sorts: “a pleasure you suffer, an ailment you enjoy,” as aptly expressed by the seventeenth-century Portuguese writer, Francisco Manuel de Mello. Saudade can only exist in the present, but cannot do without the past; it is insubstantial, but departs from the material; it is subjectively experienced but originally derived from the objective; it is a term ambiguous and universal enough to speak about practically anything: from the natural environment to man-made creations, such as music. Here the journey through saudade takes us to abstract art, more specifically, to the late abstract work and artistic philosophy of Victor Pasmore (1908-1998) who lived and worked on the island of Malta for the last thirty years or so of his life.

In an article conveniently titled, ‘What is Abstract Art?’ published in the British Sunday Times back in 1961, Victor Pasmore crystallised a mission statement which calls every abstract artist “to build from a simple but objective centre until he [or she] finds a subjective circumference.” Pasmore’s idea of abstract art, here, is one of construction and transformation – of a built landscape, metaphorically speaking. In this case, abstract art entails a process which goes against the grain of what is usually thought. It is a process of construction, not of dismantling, not of merely peeling away the layers of what is seen until one presumably arrives at the purest forms in nature. If it could be at all a destructive process, it is only so at the start in order to make it possible for new forms, images and symbols to emerge. In other terms, the value of a word, or perhaps of a letter even, must be known for it to be used in conjunction with another, and then another, until an entire sentence is formed. A language is first born this way, and only later refined.

To a certain extent, this philosophy could be found at the core of Pasmore’s interest in opposites, their juxtaposition and harmonisation. It is what enabled him to be detached from, say, the line, the dot, the material or the colour, but not from the final effect they produced when brought together. Pasmore understood that nature too, works in this seemingly conflicting way, and therefore, sought to emulate its modus operandi in his art. This further enabled Pasmore to draw references from the ancient past, rendering them relevant and modern while simultaneously respecting their original essence. Thus, what is timeless and therefore, objective, remains unchanged, but the experience of the object, which is subjective, is entirely different, unique and without precedent in the past.

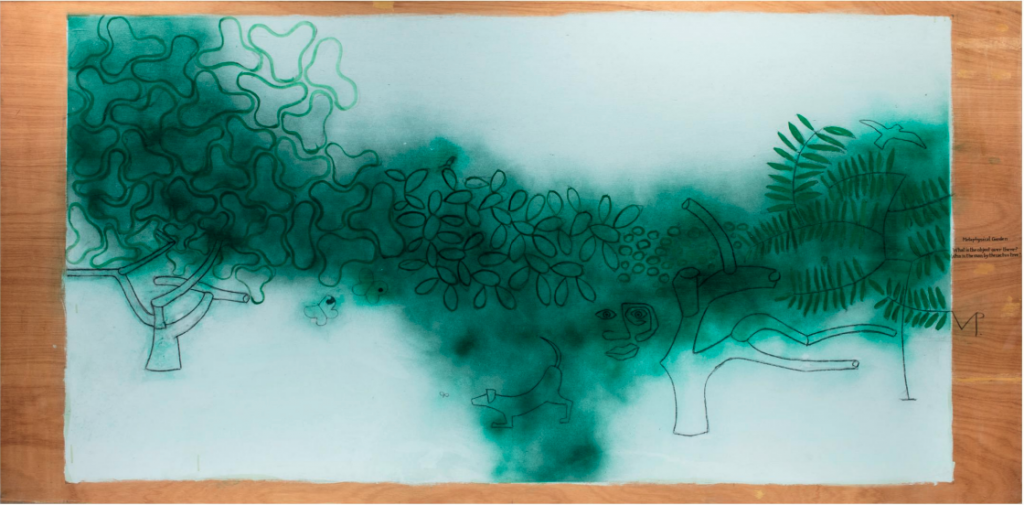

One instance which sums this up rather nicely takes us all the way to ancient Mesoamerican culture, to the so-called symbol of the atl-tlachinolli, literally meaning ‘burning water.’ In 1988, Pasmore published a book composed of a poem and prints entitled ‘Burning Waters’ wherein he paid homage to this ancient symbol that “signified the unity of opposites and the cosmological paradox.” Indeed, the ancient Mexican symbol was a visual stand in for sacred war, where water intertwines with fire – the union of two contrasting elements. This was a long-held metaphorical understanding of the cosmos, of creation, as the interminable struggle between two opposing forces. The binomial expression of fire and water, of destruction and life, was often depicted in front of the mouths of figures, or rather sacred soldiers, as if it were some form of blessing, battle cry or song. What Pasmore does instead, is juxtapose text and image in a sort of visual poem as a representation of “the tragedy of human spirit.” Here, the nature of opposites is still applicable, but the war cry now addresses contemporary man and the existential crisis of the age.

And what of the sacred soldier? It would seem that the artist has assumed this position – a median delivering two opposing, interlocking realities; the artist who is at once detached, yet whose identity paradoxically hangs in the balance between the two. Towards the end of his artistic career, Pasmore eloquently presents this world view in the Two Faces of the Turning World (1990), located at the Victor Pasmore Gallery, in Valletta. In this work, at the tip of a network of olive branches and suspended between a connected world of violence and destruction on the one hand, and of tranquillity and stewardship on the other, hangs the artist’s identity, abridged in a simple and resolute ‘VP.’

The interpretation of an image, of an artistic career or world-view is, essentially, a coming together of a number of views which are, at times, conflicting. New possibilities are born this way, whereas old ones are elaborated or, almost certainly, challenged. The Tuesday Talks series of monthly public talks held at the Victor Pasmore Gallery, and which will commence once again in November 2017, seek to adopt this multi-faceted approach in understanding not only the life, art and philosophy of Victor Pasmore and of the local and international twentieth-century cultural context, but to also outline deep-seated concepts and realities which are still pertinent to our times. Thus, our engagement with the past is indeed inexhaustible, but every attempt to do so is also tinged with a sense of something that is inevitably and irreplaceably lost.

The Victor Pasmore Gallery is open daily between 11.00am-3.00pm except on week-ends and public holidays, and is located next to the annexe of the Central Bank of Malta, Valletta. The gallery was first opened in November 2014 as a collaborative initiative between the Victor Pasmore Foundation and the Central Bank of Malta, and is currently being managed by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti. For more information and updates follow the Victor Pasmore Gallery on Facebook and Instagram or on www.victorpasmoregallery.com.