In Malta with Tears of Joy

Italian-born, independent curator Sara Dolfi Agostini (SDA) has been based in Malta since 2017 and has begun a fascinating collaboration with the contemporary art-space Blitz, run by Alexandra Pace in Valletta. Here, culture-writer Eleonora Salvi (ES) asks her about her curatorial practice, and her experience of living and working Malta.

ES: After 27 years, the World Wide Web has revolutionised our way of communicating. In a very short time, social networks and the world of emoticons have completely changed our social habits. With your exhibition Face with Tears of Joy at Blitz, you brought a group of contemporary artists in Valletta who, with their aesthetic research, ponder on these new methods of digital communication. I’m thinking of Amalia Ullman for example, and how she uses Instagram. How do you think social media inspires artists?

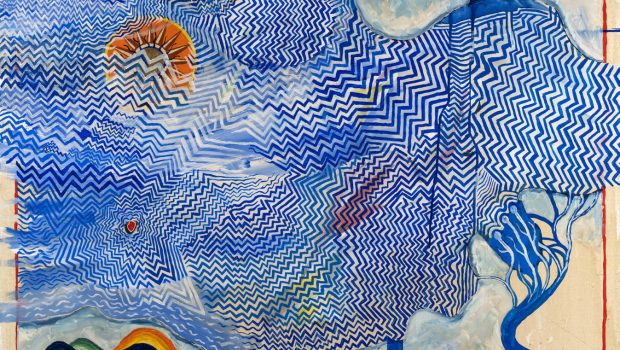

SDA: Luckily artists are not sitting in ivory towers, so they have been tremendously affected by social media, just like us. For the group show at Blitz, I specifically delved into the challenges of language in a globalised world, and how the shift from actual words to pictorial signs – like emojis, gifs, memes, or video games – has opened up a new era of playfulness, entertainment and ambiguity. Their increasing role in our lives runs parallel to, and flirts with, a desire for immediacy and a growing intransigent rejection of complexity and engagement in the real world that reverberates in our cultural, social and political behaviour. You see this in Amalia Ulman’s work Privilege, as well as in the artworks of Cory Arcangel, Simon Denny (with a new commission), Andy Holden, Maurice Mbikayi, Alexandra Pace, Rob Pruitt, Paul Sochacki, and Serena Vestrucci.

ES: When I saw Rob Pruitt’s Gimme a Hug I immediately thought of Untitled (Refrigerator) by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Contemporary art has taught us that mediums are multiple, but equally, as concepts are written, the most common types of communication are drastically evolving. Ready-mades, pop-art and then new media art, have each subverted the canonical idea of artwork. Nowadays a contemporary artist can use appliances, televisions, mobile devices, wearable technologies, etc… but beyond the screen, for a generation of digital native artists, do you think that new boundaries will be set?

SDA: I think of boundaries in cultural terms, and it makes things easier because they are not real ones – not like the physical barriers we build for ourselves. However, when artists appropriate technology and web-based aesthetics, there are often conceptual as well as technical issues to deal with. All of them bring real challenges for artists, as well as for the museums entrusted to preserve contemporary art for future generations. In the group show at Blitz, Cory Arcangel, a pioneer of tech-based art, showed a work from the series Lakes that grapples with the obsolescence of internet protocols and the good-intentioned yet still inadequate mechanisms of archiving.

Speaking of Rob Pruitt, the refrigerator is both an icon and perhaps the humblest appliance of modern society. It is part of our daily life and living spaces, and it reflects who we are by protecting what we like (to eat). In an artistic twist, what is mostly functional doesn’t lose its raison d’etre; rather, it adds a new layer by becoming a canvas for the double portrait of a father and son, which is truly completed only if you look at what is inside the fridges. In a society that often imposes function over form, where basic needs are prioritised over culture, Rob Pruitt’s work can be seen as an attempt to integrate art and life, celebrating our taste and vulnerabilities.

ES: You are a young curator and writer, nevertheless, you have travelled a lot and you have already interviewed a lot of well-known international artists and curators. Then, two years ago, you landed in Malta. Could you describe what you were met with? Who are your favourite artists and curators, and what do you gain from their experience?

SDA: There is a lot to gain from meeting the generations that preceded you, and what I have learned from these experiences levels out the parallel fear of inadequacy. But thankfully the brightest minds out there are often modest and generous if they see that your interest is genuine. I can’t mention them all, so I will only focus on two, for different reasons. Take Magnum Photos’ Stuart Franklin, for example, whose photographs were part of my first curated work in Malta at Spazju Kreattiv last year. He comes often to Gozo and never stops teaching me how to look and look again to discover the ambiguity of our relationship to the visual world. And I would also mention Jimmie Durham, recently awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 58th Venice Biennale, who has a unique way of knotting poetry and irony across sculpture, poems and even emails. It is an art of survival, and it was a pleasure to collaborate with him once again in my capacity as associate editor for the 6th issue of the magazine Arts of The Working Class, launched in April 2019.

ES: In Malta, you have already curated three exhibitions and began a collaboration with Blitz in Valletta. Do you think that soon we will enjoy art and cultural events also outside of Valletta, around the rest of the Maltese islands?

SDA: I hope so. Malta is much more than Valletta, something I am constantly reminded of every Sunday when my husband Mark and I engage in the discovery of the country, often on foot with our dog. In my second year here, I am also becoming aware of the work of many institutions focused on the conservation of cultural landmarks, like Heritage Malta and Din l-Art Ħelwa. It would be great to collaborate. One of my early working experiences was with the Biennale Manifesta in 2008, which took place in various culturally relevant – yet often abandoned – buildings in the Sud Tyrol region. It shaped my mindset to the point that every time I visit interesting architecture or landscapes I cannot help but think of a possible dialogue with contemporary art.