He saw the world through war-tinted glasses

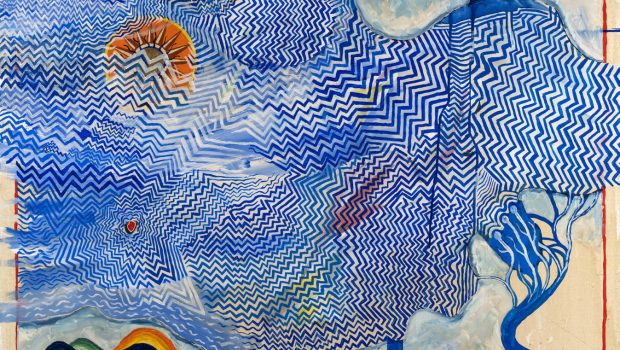

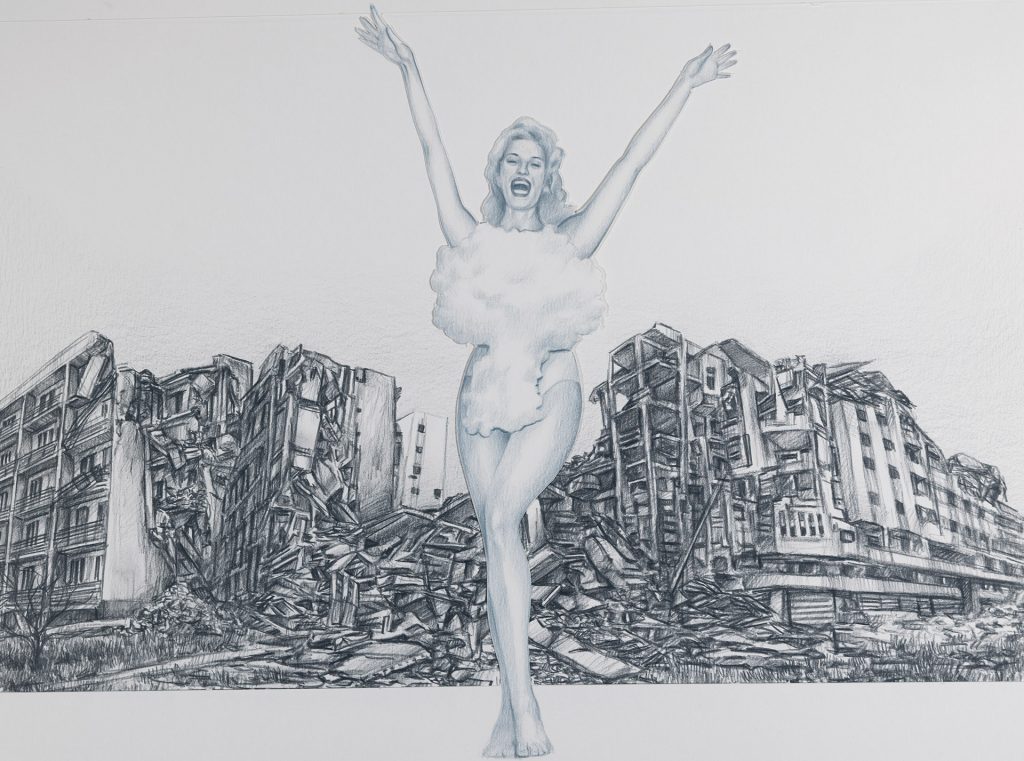

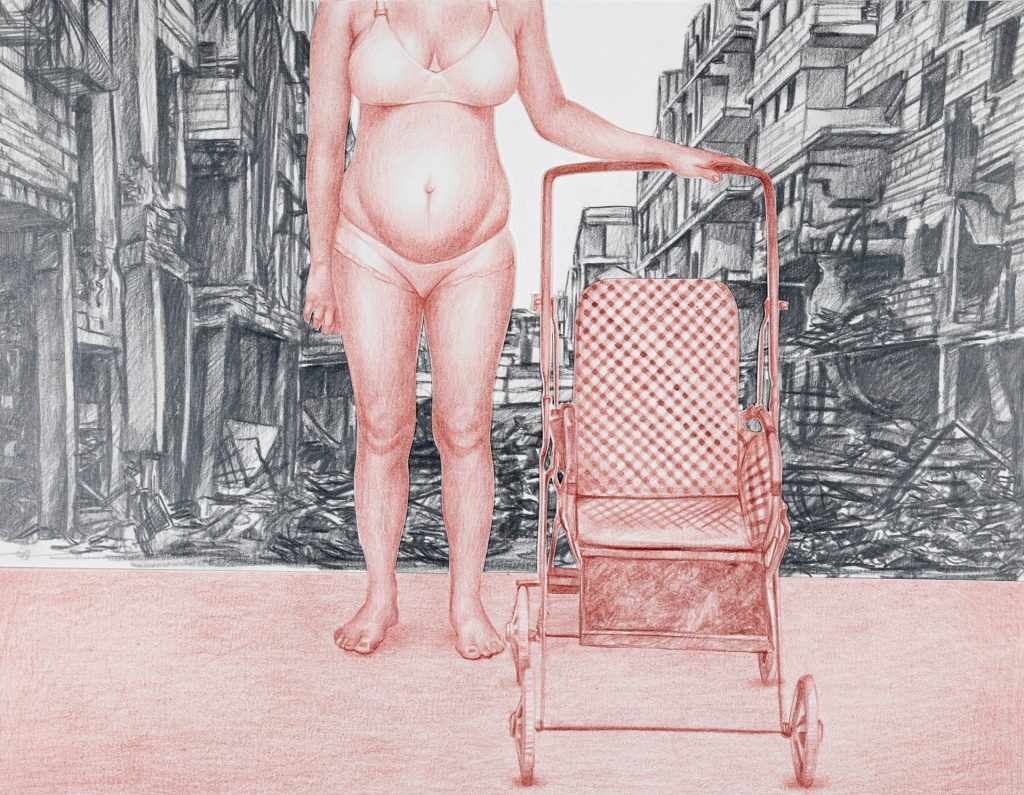

That the show Inaction is a Weapon of Mass Destruction by Darren Tanti is of remarkable magnitude is undeniable. A major solo exhibition by Artist Darren Tanti, curated by Melanie Erixon, the body of work depicts the artist’s reaction of the portrayal of atrocities committed in the name of war in the media. The works vary from large, powerful and imposing oils on canvases, to interesting sculpture.

Joanna Delia caught up with Darren for a few reflections.

JD – How did you meet your curator? What was her role in this project?

DT – I’ve known Melanie for over a decade now. We did work on multiple projects together and since Melanie and Antoine Farrugia gave me the opportunity to exhibit at il-Kamra ta’ Fuq to show the ‘Ahmar Helu w’Qares’ body of work in December 2021, we continued to work together on various other projects.

Melanie’s role as curator for this project developed in a natural way. She saw the initial artworks in 2018, way before the concept of the project was born. Over the months, as the work developed, we discussed the artworks and the trajectory that it was taking. Things gained momentum immediately after ‘Ahmar Helu w’Qares’ when the exhibition slot to show this body of work with Spazju Kreattiv was fixed. At the time most of the artworks were ready but more artworks were still being developed. During this phase Melanie kept a watchful eye, following the various trajectories my work was taking, but never meddling around with my creative process. She would ask me questions and discuss ideas, but more as an exercise to understand rather than to impose. It was closer to the exhibition preparation phase, that she took a very active role as curator and manager. She ensured that the different levels of exploration were given space throughout the space in Spazju Kreattiv and at il-Kamra ta’ Fuq.

JD – How did the idea of this project start? What was your drive and motivation for this show?

DT – This project started around four years ago as a reaction to the dangerous threats that former US President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong-Un were posing to each other; threats that could have caused human extermination on an unprecedented scale by the simple push of one big red button (quoting President Donal Trump). At the time, the world was still grappling with various news of the unfolding disasters in Syria and other upheavals related to the 2010 Arab Spring rebellions that were still happening in North Africa and Middle East. The refugee and asylum-seekers crises was all over the news and the disasters of capsized refugee boats and mass drownings were (and sadly still are) unfolding in the Mediterranean Sea. Tensions were running extremely high. In such a scenario, I felt that I had to do something, and even though I was fully aware that this ‘something’ would not really do much in the face of these tragic world affairs, I still had to do it. It started in the form of several reflections that eventually developed into small scale artworks and consequently into much larger artworks. Coincidentally, around the same period of time I attended an art/education conference in which Ai Wei Wei’s photographic interpretation of the heart-breaking Alan Kurdi’s death, was being debated and heavily criticised for being exploitative and insensitive. That particular critical argument made me think very deeply about the role of the artist in the face of war and tragedy; especially if he/she is not experiencing it directly as victim inside of the war-zone. These reflections droveme to further develop that body of work and to pursue this exhibition to the public.

JD – An artist uses artistic license to communicate and sometimes make a point. Even if that point is a personal opinion or the communication purely fantastical. This is implied, and deemed acceptable. Your work seems to criticize the fact that the media is doing the same. How does this ‘post-truth’ idea that anyone can tell a story make you feel? Do you believe that this is a new thing?

DT – Very valid points. My idea of the role of the artist and that of the journalist / media is that they have scope in their activity. It is true that in both sectors there is an element of ‘entertainment’ that is almost inevitable. Art audiences enjoy experiencing art, and the way news and information is packaged in the world of media is part and parcel of the content delivered and the experience of the viewers / listeners. Even though the identity and role of the artist is a very fluid and, I dare to say, undefinable, the role of the media is much clearer. In the case of journalists and professionals entrusted with the distribution of facts to the public, they are bound with a code of ethics and morality that demands an honest search for ‘truth’ that goes beyond egoistic interests. I’ve put the word truth in between inverted-commas because I am fully aware of the complexity that such a term brings to the argument. Nonetheless, generally speaking one agrees that truth excludes any attempts to corrupt facts and wilful deception of the audiences. In view of this simple definition I understand that whoever is reporting news, has the ethical and moral obligation to respect the verity of the news reported. In such a scenario there is no space for artistic licence, there is space for fact-checked, critically sound arguments, but no playfulness. This being said, we are all very aware that within the current ferocious neoliberal world, many individuals have exchanged their moral / ethical compass to economic interests. Thus, truth has been reduced to a bargain. I do not feel this is acceptable. On the other hand, I believe that for others working within other sectors in the media world, such as cinema and entertainment, the individual is free to use his/her artistic licence. No one watching a movie can complain that he/she is being deceived because there is a clear understanding that whatever they are experiencing can be fictional and fantastical. It is only through suspension of disbelief that the viewer gets fully immersed in the footage and visuals presented. In such scenario, the cinematographer (or any other creative individual) is free to explore possible alternatives of facts and truths. Things became more dangerous when the domains of newscasting and cinema/entertainment got closer to each other… the news agencies started to give more priority to catching the readers attention through entertainment strategies rather than to the quality of the news itself, and this, I believe, is very dangerous. The problem of click-baits – the fast consumption of information and the viewers’ inability to hold attention for long – has made the landscape more dangerous and prone to misinformation. Another serious problem related to post-truth arguments is that if one manages to learn of a false ‘fact’ going viral on social media platforms, it won’t take long for it to become an accepted a ‘truth’ – similar to the liars paradox on steroids. Moreover the democratisation of tools such as cameras, video cameras and editing software has made it easier to ill-intended individuals to propagate falsities. Even though this is not a new thing, nowadays the situation is more accentuated than in the past. I am not against the democratisation of these tools, actually I find that it is crucial that people have access to such tools so to keep authorities under check (or else we’ll end up in a regime), but on the other hand we must be aware of the aforementioned perils.

JD – The body of work also seems like a response to the diverse and yet equally important frustrations/observations related to warmongering, the breakdown of the principles of justice and basic human rights in times of war, and your response to images in the media which depict the above and although very powerful have ceased to shock a desensitized human population. What was your process? Did you start by brain storming a number of subjects you wanted to discuss with your audience? Did you collect material and then force yourself to respond as an artist? Or was it more organic? How difficult was this? And, were some issues more difficult to deal with than others?

DT – The work started and developed very organically. As an educator I am very aware of the political impact that art may have on society and I am very committed to the idea of active-citizenship. In 2018, with all the unfolding humanitarian disasters and threats of nuclear war between America and North Korea, I felt that I had to speak my mind (for whatever it may mean to myself and others). I started by collecting visual notes and jotting down reflections on paper. I followed news reports on Youtube, newspapers and other news portals to collect ‘information’ about ongoing conflicts and wars. After the initial phases of drawing and experimentations, some ideas started to become more pronounced than others – it was becoming more clear than ever that there is no way, I, as a viewer reading and researching about conflicts, can ever construct a clear picture of the same events I was researching. I felt that the same agencies that are entrusted with delivering ‘truthful’ facts are in themselves the cause of misinformation and distrust I am fearful of! I started to get angered by the ‘insensensitivity’ of random adverts popping up mid-news reports of tragedies and political strategies. Concurrently, I noticed a drastic change in the content I was being suggested on my social media platforms – almost catering my need to get to know more, thus morphing themselves into ‘feeders’ of an indiscriminate and unfiltered buffet of questionable footages. Somehow, my creative output was literally being dictated by the tools I was using – this realisation made me reflect that my true fight was against the algorithms and platforms that disseminate doubtful information. Needless to say, that spending four years, observing and engaging with news of war and human tragedy was difficult, especially when feelings of powerlessness started to seep in. Even though, during the four years, I worked on other art projects, this work was always at the back of my mind – it almost became a whitenoise, disturbing my psyche without being fully aware it. This preoccupation continued to reinforce my willingness to proceed with the project. Some of the decisions I took where not easy – for example to engage in large-scale paintings and to produce life-size sculptures. As an artist I let myself be guided by what I felt needed to be done rather than what was more logical to do. I’ve spent hundreds of hours painting works that exhausted me mentally and emotionally and I did so because it felt it was the right way. Some of the struggles I experienced when creating the initial work, which was mainly hyperrealist, led me to find alternative ways of expression, to seek ‘truth’ in abstractions, sculpture, video, sound and installations. It was during this summer, almost at the end of the process, that I was made aware of my ceaseless attempts to get hold of some ‘truth’. Teresa Bruenslow Sciberras, artist, educator and a colleague of mine, hit the nail on its head and pointed out this struggle to me. It was a moment of relief and clarity, she gave to me a strong new perspective on four years of work.

JD – Some shows and bodies of work feel balanced, loaded with political correctness. This show is all dark. Did you do this on purpose? If so why? Do you feel your intentions affected people in the ways you intended? Do you feel there was impact? What was the feedback of visitors and consumers?

DT – Some of my close friends and colleagues at work say that I am very diplomatic and try to resolve conflict before it actually happens. And I agree, as a person I hate unnecessary conflicts. On the other hand, I find that political correctness can be a bit of a double edged sword. I know that this is a can of worms, but there are times in which political correctness is (consciously and maliciously) misused, or else it is used to mask one’s true opinions for fear of being criticised or attacked. But there are instances in which one has to grab the bull by its horns, and address the situation in a blunt manner. The darkness of the work presented is a mere reflection of the darkness of the situation. I did not want to sugar-coat any of my reactions to the current situation – there is plenty of sugar-coating and alienation happening around us. Usually my work is not as dark, it tends to be provocative and loaded, but not dark. In this project I did not force myself to be balanced the content, because that balance would in itself betray the severity of the situation (at least that is how I see it). Following Guy Debord’s reflections, to make the spectacle visible, one has to resort to the exaggeration of the spectacle itself. The grotesque and hyper-accentuation are required to destabilise the comfortableness of the viewer – obviously, I do not subscribe to the doctrine of ‘shock value’ for the its own sake, that is frivolous and void, but a well-planned jolt could be very effective. One can see that there is no visible blood and gore in the exhibition, because we are submerged in such visuals, I opted for a subtler approach that engages the mind rather than the fight-or-flight response. The majority of the public shared my preoccupations and appreciated my efforts as an artist and Melanie’s work as a curator in the aim to highlight aspects of our experience of war and conflict that are taken for granted or neglected. Some of the comments in the guestbook are startling! There are those comments which are honest heartfelt reflections, other comments that are chilling (i.e. one comment was ‘Hello, the nuclear war is coming, enjoy!!!’), and others attacked the artists and poets as useless people that fancy themselves being involved in the fight against war whereas they are pseudo-active and cause more damage than good. With reference to the latter comment, I say that it only takes one right person to be pricked by art, to cause real tangible changes! It took one bullet to start WW1 and which led to WW2 and the dynamics that led to the cold war and the turmoil in the middle east to the present day… every action can have serious ramifications, thus art can never be discredited futile, as it can be the trigger the same way as a well placed bullet.

JD – You said in an interview that the highlight of your career so far was to exhibit in the Malta Pavilion at the Biennale Di Venezia in 2017 with your work Annalisa. I couldn’t help but notice that a lot of the work in this show are inspired by works at Damien Hirst’s show ‘Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable’ which was inaugurated at the same time of the opening of that Biennale. How much did that show inspire you? Did you start working on this body of work around that time? How important is it for artists to travel and be exposed to works of the diversity and caliber as those in an exposition as big as the Biennale the Venezia?

DT – Yes, I honestly feel that being part of such a great team for an event of that magnitude is a privilege. I am also honoured to say that my work is exhibited in the Imago Mundi Collection as part of their permanent exhibition and having my work exhibited in other important venues such as the Maltese Embassy in Washington DC. It is essential for Maltese cultural sector to keep its presence in the Biennale of Venice and expand to other prestigious international art events. Such platforms give our artists the opportunity to raise the bar and keep up with global trends. Living on an island has its advantages but it also reserves plenty of disadvantages – difficulties to export our work (for obvious logistical and financial reasons) may stifle our progress, and participating in events of this calibre give us back some changes to make our presence felt. Honestly, it is only now, that you are pointing it out, that I can feel some similarities between my work and the Hirst’s work presented in ‘Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable’. I had no intention to refer to Hirst, but I cannot deny that his work could have lingered in my subconscious and had influence on me. But I guess that the similarities are coincidental since the media I used have very specific meaning to me.

JD – Your works, in terms of medium seem to be finished, using more or less classical media – tangible, covetable physical objects – oils on canvas, digital prints, sculpture – whereas most of your past work was painting based. How did you decide to use such diverse media? And what effected your choices?

DT – Since the work was produced over the span of four years, it was somehow natural for the work to reflect the artistic developments I’ve been through the years. Most importantly, since I kept following what felt most honest to the theme, I let myself free from any self-impositions related to the medium. Every medium embodies the concept differently and thus offers the artist various visual and conceptual possibilities which are worth exploring. Certain decision are taken due to their visual impact whereas others are taken due to their conceptual relevance.

JD – We have seen many contemporary artists ‘stopping’ half way through their journey and publishing the documentation – leaving things open ended – as we could in fact see in many pavilions in this years edition of the Biennale Di Venezia. How do you feel about this ‘trend’? Do you feel compelled to produce finished, tangible work every time?

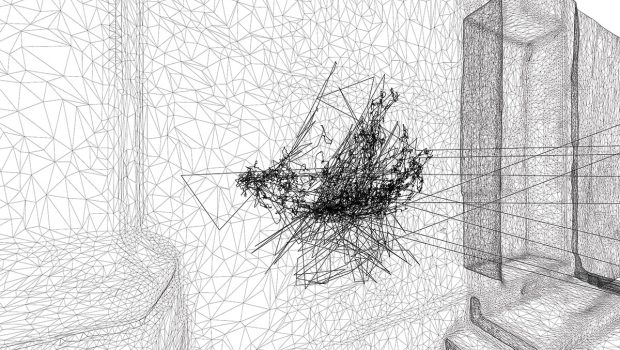

DT – As you rightfully stated, this is a ‘trend’ that is catching and was clearly visible in this year’s edition of the Biennale Di Venezia. One can see this ‘stopping’ half way through even in historical artworks or as a characteristic within movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel (and in following movements and contemporary practices). In art education, we can see that in the last decades more emphasise is being given to the process rather then to the final artwork. This approach has many pedological advantages as it allows the students to focus on the actual learning journey rather than the stress of the expected outcome. Eventually, there are those who pursue the production of a final artwork and there are those who are happy with appreciating the artistic process as a final outcome in itself. Both are valid outcomes. In my own practice I tend to favour the closure of the artworks but if need be I am ready to leave the artwork in its development, in a permanent hault. Case in point was a drawing depicting children who were victims of Assad’s terrorist gas attacks. The sight of such horrors was too much that I could not ‘finish’ the artwork and left it half way through, for me that stop in itself marks the ‘closure’ of the artwork.

JD – You are also involved in education and I know that plenty of fantastic emerging contemporary artists have had the experience of your guidance. It is only quite recent and formal educational institutions such as the university of Malta and MCAST offer the teaching of fine arts. How do you feel this has changed the scene for practicing contemporary artists? Do you see an increasing level of maturity and appreciation of contemporary art as the years go by? Do you feel that the number of artists who break taboos and boundaries with their subjects and who are more transparent with allowing their frustrations shine through their work is increasing?

DT – It is very true that I am very lucky to have had the opportunity to be part of the formation of many young contemporary artists. Together with my colleagues at Mcast and at University, I’ve seen a huge transformation in the quality of art education given to those students persuing Fine Art. We owe such changes to the huge efforts made by those who preceded us and to the work that contemporary professionals in the field are making to push the envelope forward. Even though there is much more to be done, I believe that we are heading in the right direction. Students a couple of decades ago could have never believed the extent of opportunities current art students have. The development of Fine Art programmes have contributed greatly to the quality of the local artists. These courses are usually taught by professionals who are themselves practitioners and artist. Having educators who are active in the contemporary art scene and who themselves work hard to be respected artist in the local and international sphere improves the quality and content delivered in the studio/class. Apart from having a positive impact on the prospective artists, this also positively impact the public, as more people are opening up to cutting edge forms of art and more challenging forms / concepts of art. I have seen a growth in the public’s interest in more challenging forms of art and this is very reassuring – audiences are embracing politically charged work that goes beyond mere aesthetics but transforms art into an actual agent of change. I’m seeing that many young artists are more interested in making a statement with their work rather than creating a decorative piece of work. This development in itself changes the stereotypical image of the ‘misunderstood artist living a dreams’ to an actual voice in the street to be listened and respected.

JD – The Fact you held the show in two locations – Spazju Kreattiv in Valletta, Malta’s virtual hub, and at Il-Kamra ta’ Fuq in Mqabba, simultaneously while also actively organising tours for the regulars at the bar there to come visit Spazju was heart warming. Is bringing the art to every corner of this country and using art to speak to the people outside of the art bubble important for you in your opinion?

DT – I think to speak to people outside the art bubble is very important. It is very easy for us in the art community to focus our attention on ourselves – it is easier as we speak the ‘same’ language and we broadly speaking we share very similar views on various issues. We can easily build a wall around us and make our practice inaccessible to others outside the wall. But I feel that if we do so, we miss the point of our activity. I believe that everyone has the right to art, because art is not a mere product but it is the manifestation of humanity itself. I always say to my students that ‘Art is about life’ (even if it speaks about death) and by this I refer to the ‘human experience’. In this sense everyone can relate to the artist’s expression even if at first it seems distant and alien. At times it only needs an introduction, a couple of written sentences or else some time to take it in but at a point or another there will be a reaction, even if it is a refusal. At il-Kamra ta’ Fuq one can observe a very particular phenomenon in which locals who have never had any interest in art whatsoever, started to get engaged in art. The regulars who usually went at New Life Bar for the usual cup of tea, are taking the initiative to go up in the Kamra ta’ Fuq and see art and engage. They discuss the work, share ideas and opinions and are appreciating what once felt so distant to them – art. Even in their adulthood and senior years, we are seeing that people are eager to educate themselves and exploring culture, and this is amazing. It gives me great joy to see the community opening up to art beyond the comfortable zones – which was mainly bound to sacred art or decorative art. Melanie and Antoine work very hard to give everyone the opportunity to visit the space and meet with the artists. Apart from that we are seeing that at il-Kamra ta’ Fuq, people from every part of society is meeting and spending time in a positive art environment.

JD – What else do you as an artist think should be done to increase interest in contemporary art to the Malta based public? What can be done to increase the visual literacy of Maltese residents?

DT – There is much that is being done in this regard, and there is so much ore that still needs to be done and improved. Perhaps two words that I thing I’d like to point out is more commitment and perseverance. We as people in the art world need to be more actively engaged with the public and draw them in, if need be organise tours to shows etc. It might seem ridiculous but perhaps some people only need a nudge to get them going. Another thing that I’d like to see happening is that we educate our public to invest in art and buy the work of Maltese and Malta-based artists. When buying art and bringing it to home, or putting it on display in public spaces, it contributes to continuous visual formation and literacy. Needless to say that, we need to save guard quality at all costs and educate the public that not every painting or drawing is ‘art’. In relation to this, I firmly believe that we need more art critics that do not shy away from speaking up their mind and point out valuable art from hobbyist takes on art. Gallerist too have a responsibility in this regard, they must exercise professional and informed judgment to who display in their gallery. But I am opening Pandora’s Box in here, perhaps we develop on this argument in another interview.

JD – What’s next for you?

DT – I have a couple of projects in the pipeline amongst which another solo exhibition in December 2023. I would like to explore lighter subject and I am also looking forward to explore abstract art, installation and sculpture. I have new work which is very different from that shown in ‘Inaction is a Weapon of Mass Destruction’ and I am very curious to see how it will develop and how it will be received once it is exhibited.