“Everyone is an artist”

On the occasion of the 100th birthday of Joseph Beuys, a large number of exhibitions are being staged in Germany

The influence that the German artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) had on art history can only be properly assessed in retrospect. Aside from his work, his self-dramatisation still serves as a model for artists today.

It began ingloriously – a child of his time, Joseph Beuys joined the Hitler Youth as a teenager and volunteered for the Luftwaffe in 1941. After training as a radio operator, he was deployed on the Eastern Front. Many of his drawings have survived from his time at war.

In March 1944, Beuys was flying a dive bomber (Stuka) that hit the ground due to poor visibility and crashed. A German search party found him as a survivor, and three weeks later he was able to leave the military hospital. However, the incident served him throughout his life in creating a myth around his oeuvre: Beuys liked to work with organic materials such as fat, honey and felt. He claimed that nomadic Crimean Tatars had rescued him after the plane crash, packed him onto a sledge and anointed his wounds with animal fat. In the process, he was kept warm in felt for eight days. This legend was only disproved in 2000.

After the end of the Second World War and a short period as a prisoner of war, Beuys returned to his parents. In his home town of Kleve, he joined an artists’ group as early as 1945. He studied monumental sculpture in Düsseldorf and was allowed to work as a ‘Meisterschüler’ (postgraduate) on major projects such as Cologne Cathedral. At the same time, the class was intensively occupied with the philosophical teachings of the anthroposophist, Rudolf Steiner. This is where Beuys’ later world-view and theory of social sculpture took form. He demanded that man, society, be shaped by the means of art.

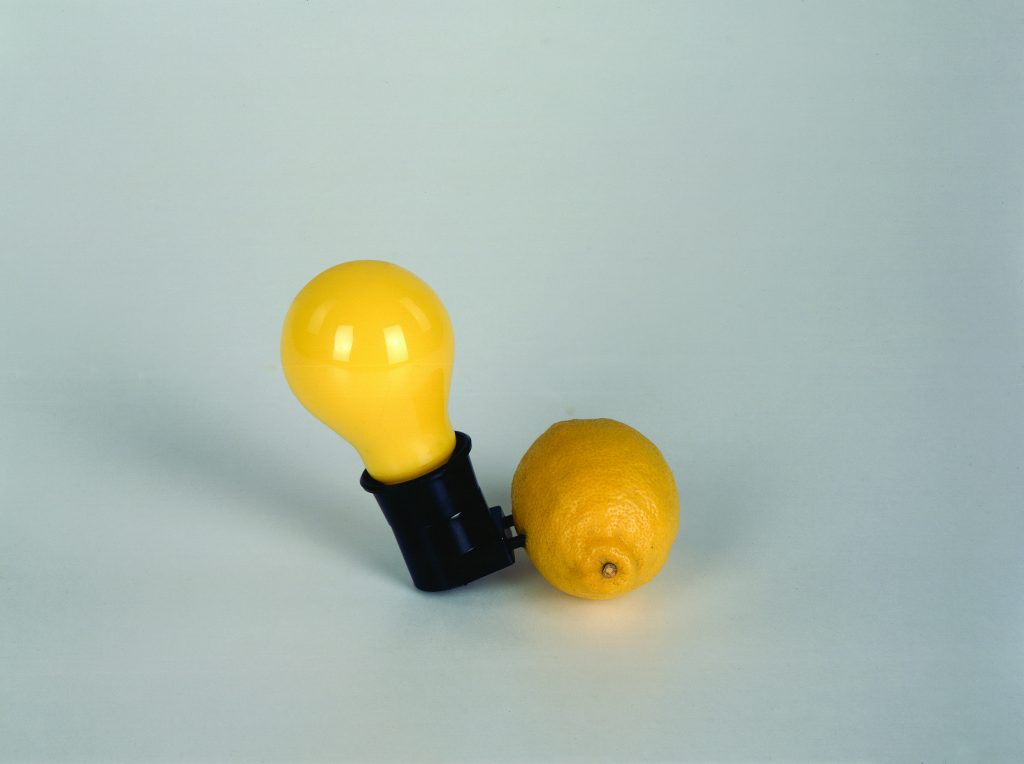

From 1961, he held the chair for monumental sculpture at the State Academy of Art in Düsseldorf but soon attracted more attention because of his unconventional performances. He supported the new Fluxus movement, according to which it was not the work of art that mattered, but the creative idea. Beuys coined the ‘expanded concept of art’, which took social aspects into account: “I am certainly not an artist. Unless we all regard ourselves as artists, in which case count me in. Otherwise, no,” he said shortly before his death.

However, his provocative postulate that “everyone is an artist” angered the establishment. At the Festival of New Art, a student punched Professor Beuys in the nose. Beuys rejected admission procedures such as application folders and took all the rejected applicants for a teaching degree into his class (which thus grew to 400 students). After the Ministry of Education and Science did not approve of his action, he and a group of students occupied the secretariat of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1971. In negotiations with the minister, he obtained a one-time exception. But when Beuys did the same the next semester and allowed 268 students in his class instead of 30, he was dismissed without notice and escorted out of the academy by police officers.

International artists such as David Hockney, Jim Dine and Gerhard Richter demonstrated against the dismissal because Beuys had celebrated groundbreaking successes in previous years. He exhibited regularly at Documenta in Kassel/Germany, probably the most important show for contemporary art, as well as at the Biennale di Venezia. For his first vernissage in a commercial gallery (1965), he made guests wait three hours outside the locked door. Meanwhile – as they were able to look in through a window – Beuys walked through the presentation with a dead hare in his arms and explained the pictures. He himself was covered in honey and gold dust. With this satirised ritual of ‘explaining art’, he criticised what he perceived as an elitist approach to art. Today, the performance is considered a key work, which Marina Abramović repeated in 2005 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York to draw attention to its topicality.

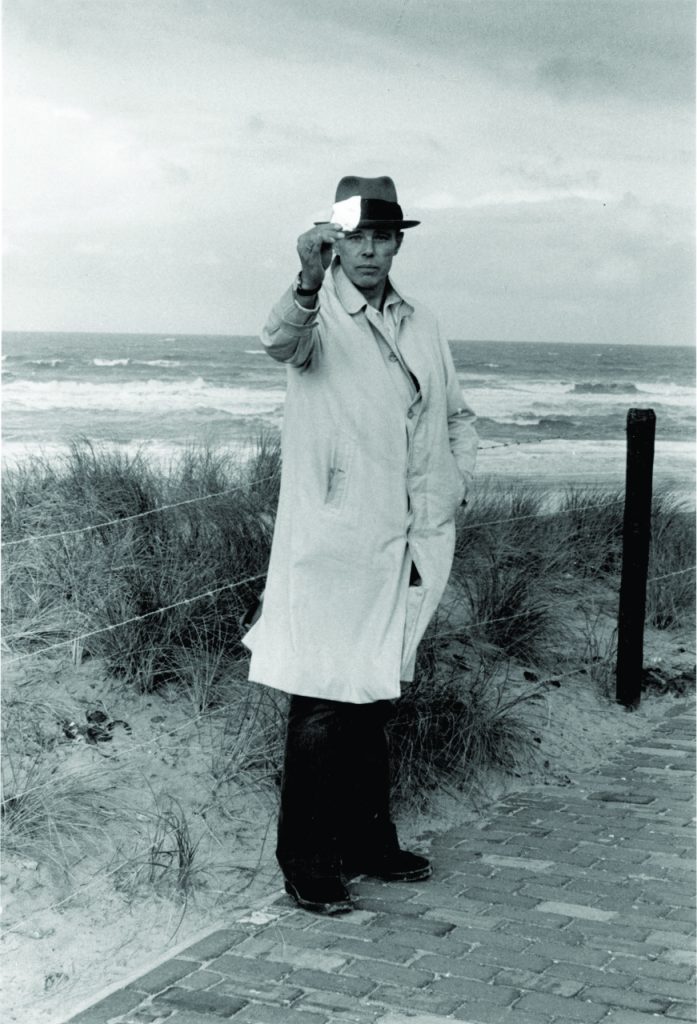

In a New York gallery, Beuys once spent three days living with a coyote, mostly wrapped in a felt blanket and leaning on a shepherd’s crook (I Like America and America Likes Me). In another performance, he cut his finger and bandaged the knife. His later iconic outfit – jeans, white shirt, anglers’ waistcoat and felt hat – is said to have been advised by his wife so that he would attract more attention during an interview. He spoke to the media a lot and used the emerging medium of television to spread his art. According to his biographer, he was an ideal-typical counterpart to Andy Warhol, the two worked together in 1980 for a gallery in Naples.

At the end of the 1970s, the Green Party emerged in Germany and Joseph Beuys ran for the European Parliament. In an election campaign song, We Want Sun instead of Rain, (= onomatopoeic: Reagan), he sang in 1982 against the rearmament plans of American President Ronald Reagan and nuclear power plants (and for the expansion of solar energy). When Joseph Beuys died at the age of 64, he had proven that as an artist you can critically question politics and society and integrate them into practice.

—

The main exhibition is scheduled to take place from 27 March to 15 August 2021 at the k20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. Due to protective Covid-19 measures, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen was closed until further notice at the time of going to press. The organisers are working on an alternative digital opening scenario. www.kunstsammlung.de/en/ An overview of the planned events: www.beuys2021.de/en