Art in Life and Death – A Legacy of Patronage

Ann Dingli interviews Jhonny Roldan – known artistically as JRoldan – a London-based visual artist who worked for over a decade with Christian Pandolfino – an art lover and patron who was killed in Malta earlier this summer.

It was only in the nineteenth century that the modern role of the artist as autonomous genius gained ground. Before that, artists were overwhelmingly beholden to their patrons – the relationship between creator and benefactor propelling themes in art history that would permanently shape the world’s visual heritage. Patrons wielded their social, political and religious standing through works of art, from the diorite princes of the Ancient East to the writhing gods and saints of Italy’s Renaissance. Often a symbolic percolator for illicit behaviour – money laundering, sexual mania, and the lure of murderous violence – the whispering eroticism of mythological frescoes were as much passports to the identity of their sponsors as the throbbing carnality of the great Baroque canvases. Same stories, different eras.

Whether well or ill-intentioned, benefactors have always represented humanity’s obsession with the romance that art permits and promises – a pull that eclipses class or education, but that invariably demands hefty financial resource. At points throughout history, relationships between what would today be classified as ‘creatives’ and ‘clients’ were strained, soured and at times ruinously fated. Yet at others, they saw the fruition of some of the most transcendental moments in history – a meeting of mind power that resulted in the alchemy of art’s creation.

In 1990s’ London, it was through social networks of likeminded individuals that a young Colombian artist met a retired doctor turned banker. Jhonny Roldan, a visual artist having rejected the formality of the Slade School of Art met Christian Pandolfino (or Bambi Pandolfino, as was his preferred art world pseudonym), who himself had cast off the trappings of a career in finance. What would follow was a relationship spanning over fifteen years. A bond in which the artist once again occupied a station of manufacture, translating grand ideas born and exchanged between him and his intellectual and financial partner into visual experiments.

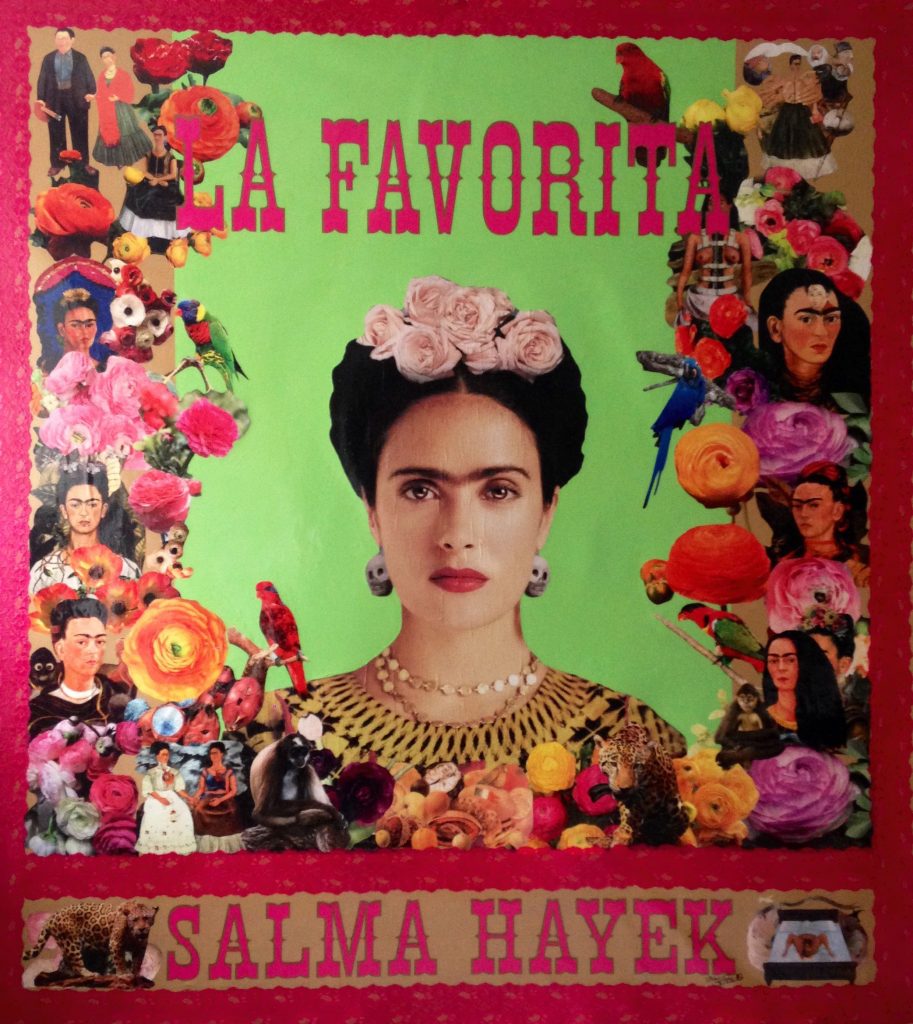

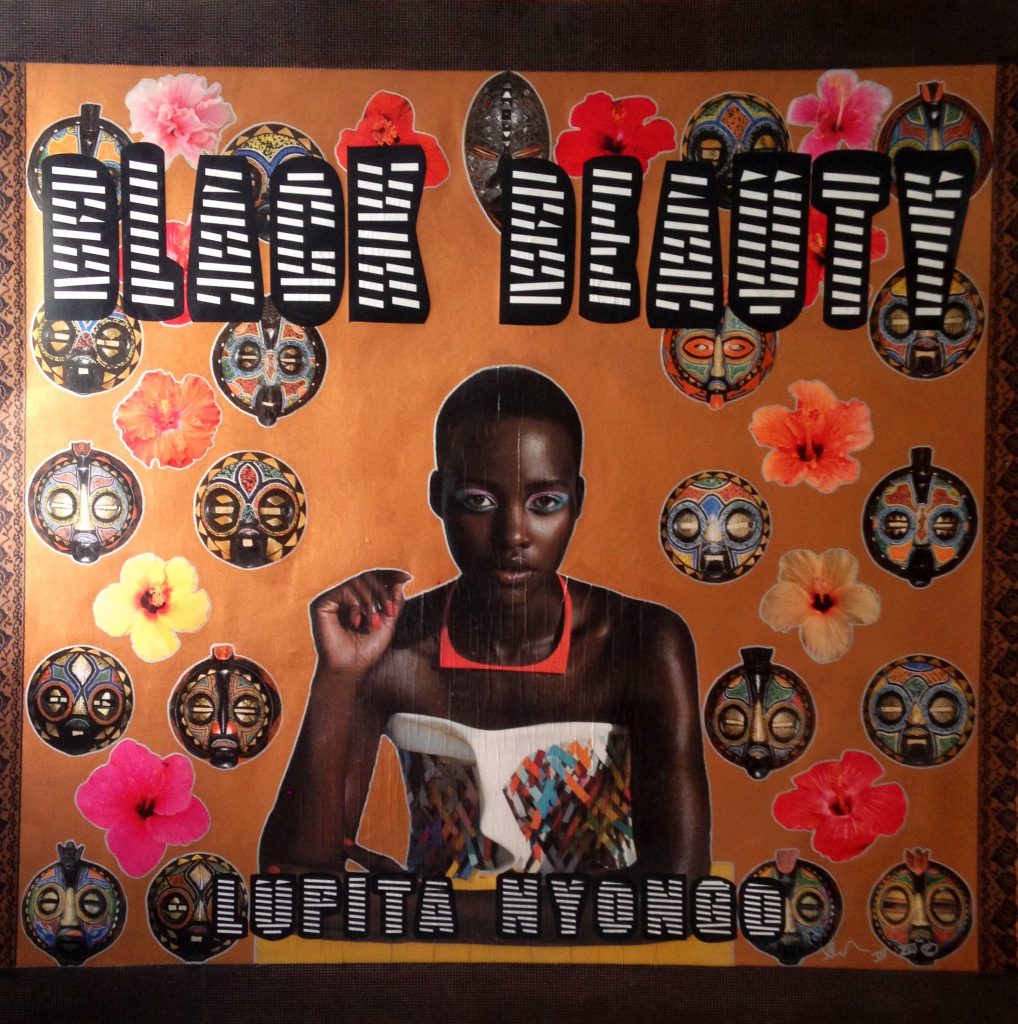

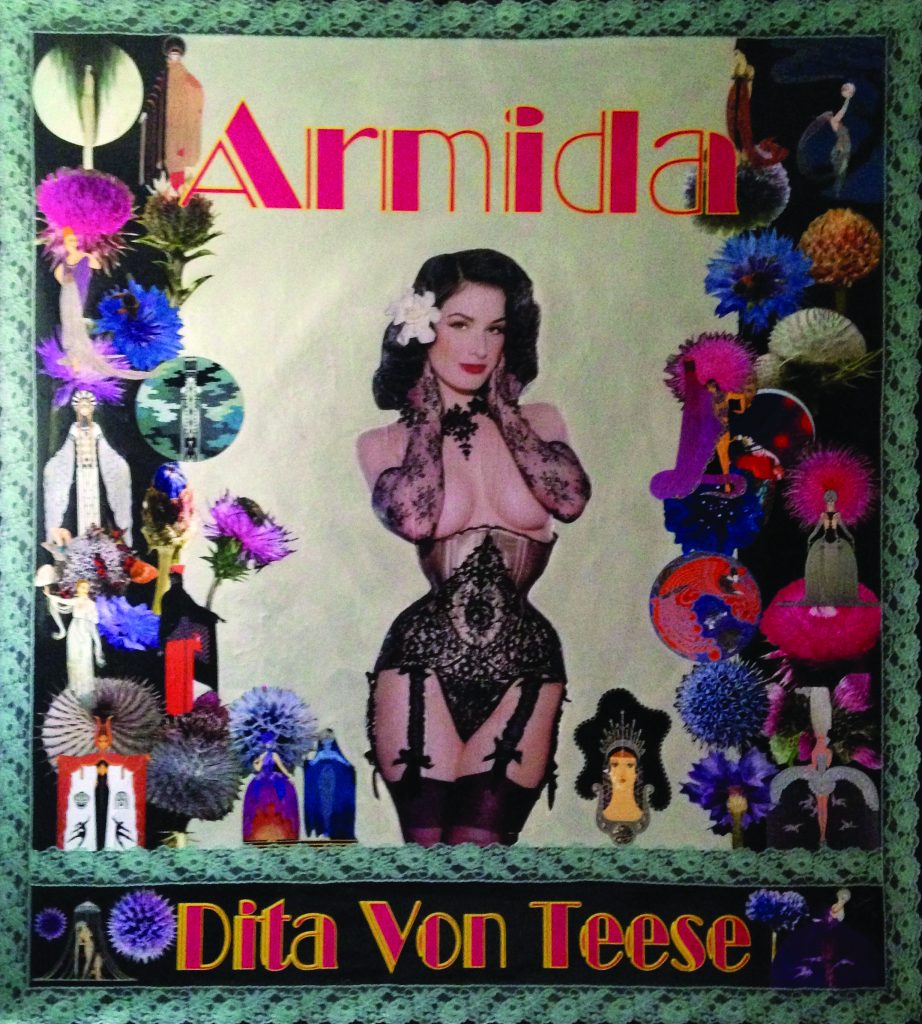

Twenty-five years down the line, JRoldan is still making art in London. He creates work that has been described as relating to American abstract expressionism and the gestural abstraction of post-war Europe; but which over time has increasingly inducted the visions and mythology of contemporary pop culture – seemingly a stylistic hangover from his time spent with Pandolfino. Their relationship ended over four years ago; and as with many forceful bonds, concluded with dramatic swiftness. In summer 2020, Pandalfino was murdered in his home in Sliema, Malta in a rapid and fatal break-in.

“I met him through another friend,” JRoldan recounts over a botchily connected video call from his studio-home in central London. He describes his conflicted relationship with the art world and community, admitting in one fell swoop his scorn for most conceptual art and his disinclination for public relations and selling his own work. “I like the craft involved in art – I hate PR, I hate sales, I’m definitely not a good salesman. But then again, I have met some good people. One of which was Chris. I met him about 25 years ago, and he started buying my art.”

JRoldan recounts his long history with Pandalfino, hopping with anecdotal vigour from one phase of their friendship and business partnership to another. Repeatedly, he characterises their time together as ‘intense’ – a whirlwind of conversation and creation that equally fuelled him and wore him down. Over the years, they developed a language for art together, sharing dialogue on trends and topics that sporadically consumed Pandolfino. Their love for art, literature and opera was the common thread that stitched through their friendship.

“We had endless conversations about endless topics,” JRoldan recalls, “from cinema to opera to artists and so on – we kind of clicked. It was amazing, and time flew by”. He describes the years they spent together with both clarity and candour, refusing to level neither unmerited niceties nor unqualified criticisms towards Pandolfino.

“[Chris] was very eccentric. He would send me 30 emails in one day – it was a lot of work and could be quite exhausting. But somehow, I liked it. Because I was single and I had been single for a while – which he also was at the time – so the relationship kind of filled a void, of companionship or whatever. I was very young back then myself, but as Chris was growing, he started to give me ideas – why don’t you do this, why don’t you do that? And that’s how it all happened. So, it began with him buying my work – buying and giving to his friends or collecting for his house. But eventually it became a process where he would have an idea, he would ask me to execute, and then he would buy it. And he would keep asking for work until, next thing I knew, six months would have passed, just like that.”

The results of their partnership remain largely inaccessible to a wide audience, save for his friends and family – the latter JRoldan describes as one of his mentor’s greatest loves. When asked if Pandolfino was moved to exhibit the fruits of their discussions and production, JRoldan indicates that he wasn’t. Pandolfino, as JRoldan describes it, was more consumed with the act of translation – of discussing his fiery ideas and having them laid out in two-dimension. “To me, I felt like I was an apprentice,” JRoldan explains, “like [Chris] was mentoring me. Chris had a lot of knowledge – he was very well read, and I think I am too. So, we had all these debates and it was quite fun.”

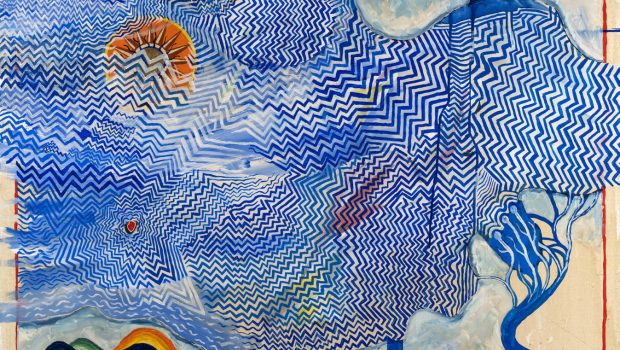

“But he got so intense at times. We would spend a year or two working on the same series. The last series we did was about migrants – and he would sometimes spend five hours straight talking about the issue. The intensity was… a lot! But, again, he was fun – although I did not agree with many of his views. When the issues and stories of migration began to blow up, he got very into it and we started creating these mural-sized works. You know, like six metres by two metres – gigantic. They were really cool, I think, very pop. Some could have been better – I could have retouched here and there – but I just needed to get the job done. They were very controversial, and they don’t necessarily express my own feelings. It was all to do with him. I was more of an executor.”

It was at this point in their story that JRoldan expressed his desire for a recess – a break to gather his energy and restore his mental strength. He travelled to Japan for a month, and by the time he had returned him and Pandolfino had severed ties. Apart from a brief encounter in a London café years later, the next time JRoldan heard Pandolfino’s name was in the shocking headlines connected with his death.

Their separation clearly marked a shifting moment in JRoldan’s career – a calm beyond the giant storm of Pandolfino’s frantic cerebral output. JRoldan’s retelling of their estrangement speaks of both redemption and wistfulness; a genuine account of a man who has laboured and lost alongside another, whether by default or design. He expresses the strangeness of their bond with frankness; admitting that the peculiar way in which they worked is what made the art they made so bold and uncompromising.

“That’s always the situation when you’re working as two artists. For example, I’m good friends with Pierre et Gilles. And, you know, I felt like [mine and Chris’ partnership] could be like that kind of situation. Like Gilbert and George. Because we were spending a lot, lot, lot of time together.”

Post partnership, JRoldan’s work settled back into his own style. “My own artistic position deals more with beauty. Chris is not the only person who passed away tragically in my life. I grew up with a lot of tragedy. Most of the people in my childhood don’t exist anymore. For this reason, I could relate to the art we were making together, and at the beginning I used to draw a lot of guns and things. Now, I draw butterflies.”

JRoldan’s work and practice does appear less feverish than the older artworks, images of which have been sent through messages and emails as a consequence to their captivity inside Pandolfino’s home. JRoldan’s process is laid bear in his frequent Instagram posts, many of which show him meticulously layering his work in careful detail to the background of opera music – an implicit reminder of his former partnership, and an echo of the stories shared between two minds propelled by the prospect of creating art.

JRoldan closes off his account discussing Pandolfino’s creative energy and the volume of work that still exists as its tangible yield. “Deep down I know [Chris] would have loved to be some kind of famous artist. Give him a chance to be that – we have the material. There are hundreds of works – and they are not just little paintings. Using them in the right way could give him a legacy”.

The destiny of JRoldan and Bambi Pandolfino’s work remains to be seen. Yet as JRoldan carries on his work with the stamina of a more mature artist, the impact of his patron’s influence seems to persist. Pandolfino is there in the opulent colours, the expansive dimensions, and the irreverent pop imagery that still stands as a backdrop to JRoldan’s practice.

Meanwhile, the story of a man who by this account was fired by the power of art, still clings to the potential for relevance. As with the art world’s vast history of patronage, the most valuable result begotten by deep artistic connection is the work itself. The threat of its dormancy is legitimate, with the justice of Pandolfino’s death reasonably overshadowing any other conceivable priority. But the decades’ worth of art that two men created together should be kept alive; because as history has demonstrated consistently, art is always stronger than death.