The Alpha and the Omega

A conversation with Julien Vinet

I ask him why he chose to work in Malta. “The light” he says, as if he’s a lost impressionist spending his days painting the shimmer on the waves of a sun-clad Mediterranean. But his work is exclusively black on white: thick, viscous ink on an off-white page, perfectly balanced, perfectly commanding and perfectly in control of its own space.

For Julien Vinet, it seems that the most beautiful contrast in the world is that between black and white. Black and white is the alpha and omega: a perfect duality contained in one composition. And the light in Malta allows him to investigate this contrast further, to see the graduation within the black and the variations in the white. This is because, as you look deeper, you see that the black is not really black: it possesses a lustre and a sheen that almost make it vibrate in the evening light. And the white is not clinically white, but consists of delicate variations of cream, pale browns, and gentle, sloping off-whites.

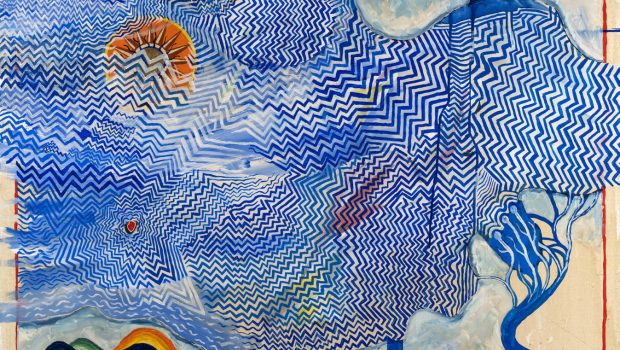

As I visit Vinet in his studio in Valletta, he is working on a series of pieces using black viscous ink on old, used naval charts that he salvaged from a Maltese smuggling boat. The contrast between the strong, viscous black surfaces and the fine navigational detail, as well as the age of the paper, is striking: there’s something that draws you in, pulls you closer.

We talk about lots of things – from his time as a young man in Japan to the changes he has seen in Valletta over the last few years. He gets excited talking about a particular busker on Republic Street in Valletta as if it’s a deliberate, contemporary art performance, but he also remembers Austin Camilleri’s Żieme installed in front of Malta’s Parliament Building in 2014 and the reactions it attracted from passers-by.

‘What sent you to Japan? I ask him. Vinet travelled to Japan at the age of 22 and lived there for almost a decade, before moving to Malta with his Japanese wife. “I like when things change” he replies, “When things are open”. There’s a strength evident there, a determination – somehow – in the act of embracing a different culture, of self-challenging and looking for change. Indeed, after about eight years in Malta, Vinet is ready for change again; this time to the not-so-far away city of Berlin.

The influence of Japanese aesthetic is evident in Vinet’s work, from the calligraphy-like gestures in the ink and the purity of his strokes, to the balanced compositions they create. In particular, he emphasises the negative spaces in his work: the empty space left around the black is as important as the black itself. What is left out is as strong as what is put in. It’s the alpha and the omega again, but this time in space rather than colour.

Vinet’s Frenchness comes through in our conversation, somehow. It’s there in his egalitarian belief that art should be for everyone and not confined to an elitist contemporary-art cohort. It’s also there in his work: in the confidence that’s contained in his brushstrokes and in his confidence that his abstract work can speak for itself without a theoretical explanation or defence.

For Vinet, art should “strike you in your soul” – creating or viewing art is not only a cerebral process. He describes seeing five of Monet’s Water-Lily paintings in the Chichu Art Museum (Chichū Bijutsukan) in Naoshima as being a spiritual experience. For him, art provokes feeling: devotion or even disgust but, above all, a feeling or a connection.

He talks about the “personal experience between you and the work”: only you can have the connection you have with a work of art – nobody else can have that same experience.

We talk about why he works in this way; in monoprints, pressing paper onto a glass sheet that’s been inked with a mixture of printing ink, glue and oil. (He’s been working in this way for the past 15 years). He tells me that the technique allows him to relinquish control. Indeed, it’s a technique that forces him to allow some serendipity into the process of creating. It strips the artistic act back to strokes and gestures, to a distillation of spirit.

We also talk about art in Malta, about how sometimes it can be too self-referential and not sufficiently open. We discuss the Malta Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale – a big moment for Maltese contemporary art – and while Vinet is not harshly critical of it, he does suggest that the transcendence of Malta’s national identity could have been more open, and more universally-themed for an international audience.

Somewhere there’s a contrast between his secularist or egalitarian outlook, and the almost spiritual qualities he attributes to art: it’s a gentle contrast that is reflected in the balanced tension in his work.

The only colour you’ll see in his work is the bright red mark made by his ‘seal’, which was made for him by the same stamp master as the Japanese Imperial Family – a calligraphy and stamp master certified as a Living National Treasure. It’s Vinet’s signature, that he only places in a carefully-considered spot on a work, once he considers the work to be finished and fit to leave his studio. The act is like a blessing but it also contains a contradiction that provides another balance-point. Now the visceral black and white is on one side of the equation – on the other is the small bright red square of Japanese characters.

Does an artist’s work reflect his character and how he lives his life? Can an artist’s character be distilled in the brushstrokes of his work? Whether Vinet himself is a perfect balance of strength, subtlety, spirituality and serendipity, I don’t know. But there’s something in his work (and in his conversation) that is simultaneously abstract yet meaningful that makes it compelling.