Reclaiming Her point of you:

A Conversation With Tina Mifsud

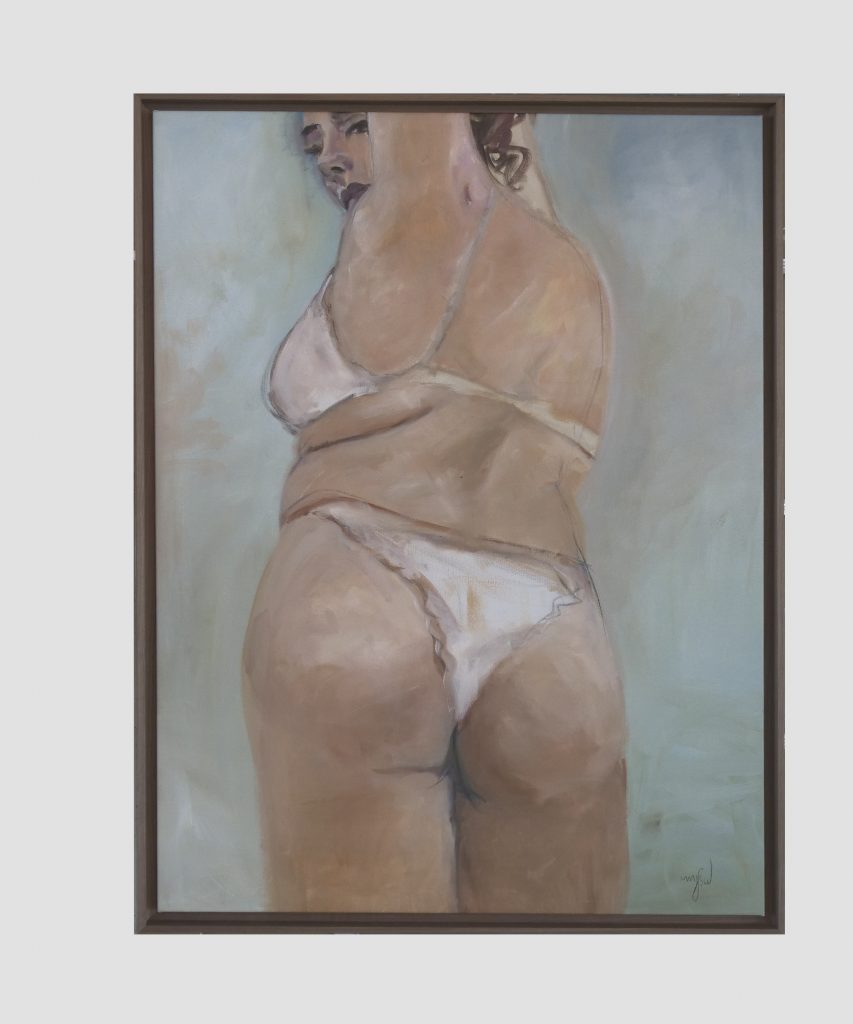

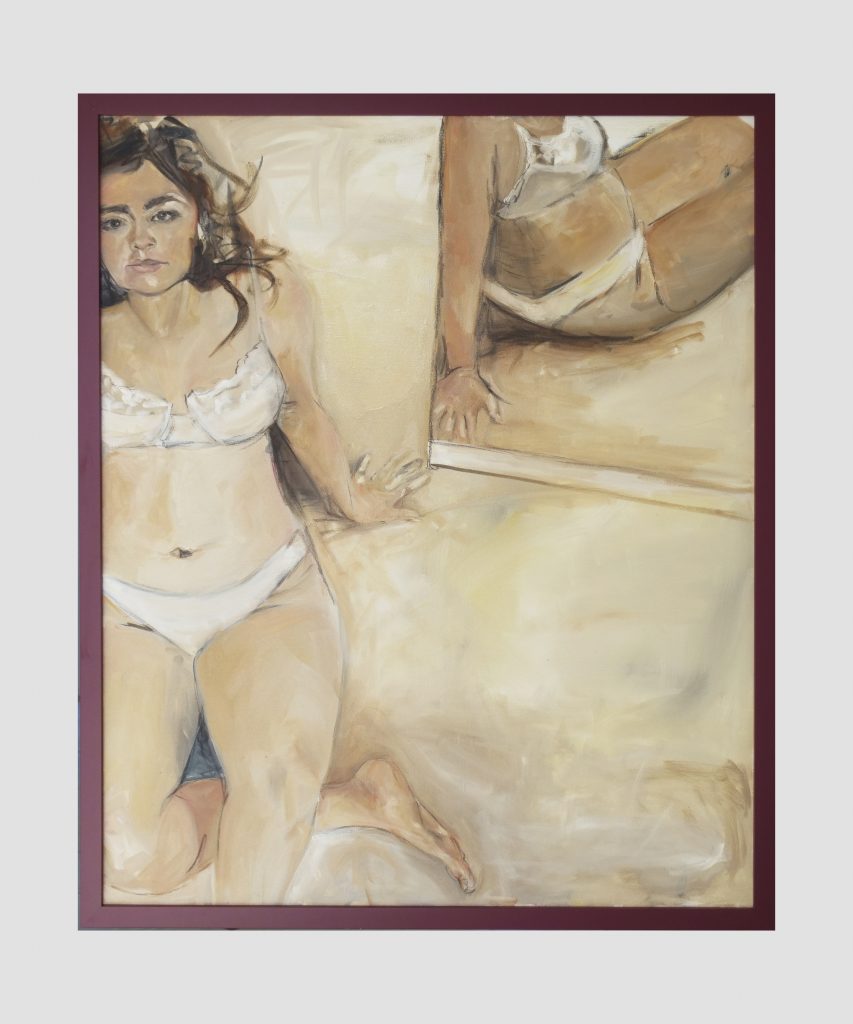

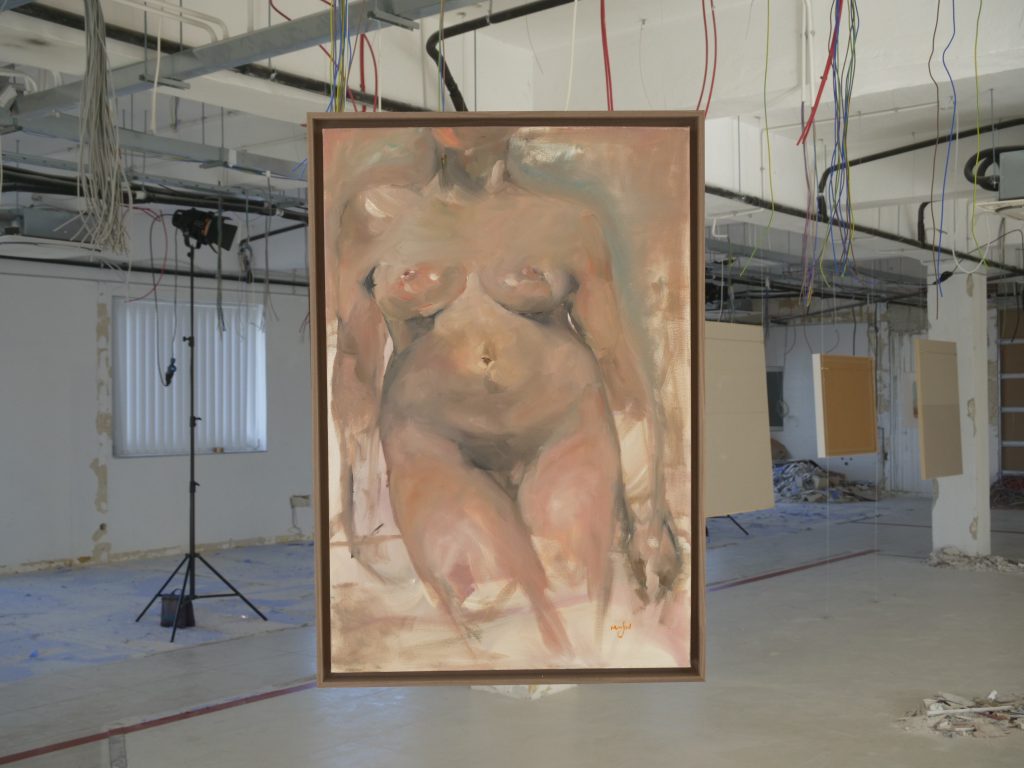

Tina Mifsud presents a fresh perspective to a long-discussed issue in the history of art, namely the female nude. Take, by way of introduction, her solo exhibition, point of you, which was opened last December in Malta. In it, Tina dove headfirst into her relationship with her own body; her obsession with self-portraiture and her most debilitating insecurities. Maria Theuma meets her in conversation over Skype to exchange ideas, recollections and anecdotes from point of you; discussing the checks and balances of gender privilege in the art world, and gushing over their mutual love for Jenny Saville.

MARIA: Tina! How have you been?

TINA: Good — very overwhelmed with the feedback, but all’s good. I’m not used to it, but it’s nice, and it’s part of an artist’s process as well, I feel.

MARIA: How has the feedback been?

TINA: It’s been mostly good, so I really can’t complain — but, then, sometimes I get a bit confused because I start to wonder if people are really being genuine about it.

MARIA: You yourself have been so genuine in what you have created. Do you feel that that requires a genuine response from the viewer as well — how important was that for you?

TINA: I mean, it’s a sensitive topic in general. I’m still a growing artist, I’ve still got a lot to learn, and I want all the constructive criticism I can get. And because the contemporary nude is such a new topic for Malta, I sometimes wonder if people have been shying away from giving me genuine criticism.

MARIA: Right. And, broadly speaking, there have been so many conventions around the idea of the female nude — not just with regard to the way it’s created but also how it’s received. Over the years, it’s been policed and mostly looked at through the male gaze, and that in itself means that there have been certain rules to abide by when looking at a nude. I was wondering, how do you want your audiences to look at your nude, knowing that there are entire histories of culture and power that inform that ‘looking’?

TINA: What I meant by ‘a genuine response’ is that you almost feel like the critique is doubled, in the sense that a viewer can be criticising the topic of the paintings, which is me, the female artist, as a body and a nude, but also my technique, you know?

MARIA: How would you describe your relationship with the question of technique? In my academic research, I’ve looked at the nude in its classical form, which has been, of course, a great topic throughout art history — telling us how to ‘correctly’ paint and look at a nude, as it were. And, often, there’s this sort of dichotomy — a discrepancy, if you will — between a nude and a naked body, and technique is projected as that which can differentiate between the two, between perceived artistry and obscenity. All of which, of course, has been dictated throughout history by men. To what extent would you consider being a female artist, working in this tradition, an inherently political and defiant act, and to what extent is technique an antagonistic component within this framework?

TINA: Yes, exactly. I always say that I want my work to be politically engaging — I want to strike conversation. I want people to talk about my work but it’s a weird thing because sometimes I feel like we’re not at that stage yet — where we’re allowed to have that conversation, you know?

MARIA: I agree. Malta definitely has its own specific weirdness in this regard, and I understand your concern with how your work gets to be technically perceived and critiqued in this country — but at the same time it’s a problem that’s been inherited, I think, from thousands of years of art history.

TINA: Yes. I do need and crave an audience’s response but, at the same time, where is that response coming from exactly?

MARIA: I would say that, as a female artist painting the female nude, locally, you find yourself in a cultural and historical vacuum, which exists, at the same time, side by side with the broader international histories surrounding the nude and its ramifications. When I came to your exhibition, you and I talked about how when people refer to the nude in art, they automatically tend to think of the female body and not the male body — not that the male nude doesn’t exist — but the female nude in history has been formalised to such an extent that it has become almost synonymous with the female body. And then you told me that you’d been told by a local art historian that you were actually the first female artist painting the female nude as an exercise in self-portraiture in Malta. Honestly, there’s so much to unpack there — in that first-ness.

TINA: I had no idea I was the first one to do this, and it obviously came as quite a surprise when I found out. My initial reaction was, “oh, that’s quite cool”, but then I realised how sad it was that such a topic hadn’t been tackled before. And then I thought about how I’d set out being so cautious with how I painted myself; the anxieties I felt about making sure that what I painted was not too flattering, and that people wouldn’t take it as a kind of a statement about me being too full of myself, you know? In fact, at first, the collection started off in that manner, where I was, like, “Okay, I’m going to make myself look really unflattering”. And then, along the way, as I studied my own anatomy and got more confident about it all, I said to myself, “No, I want to highlight how well I know my body”. As we’ve said, there’s no recollection in Malta’s history of art of anyone doing anything of this sort but the response has been really positive. I wonder why that is. I know that my work isn’t perfect yet or even anywhere near where I want it to be, so, like, I keep asking myself if it was well-received just because its message is powerful, and if it made people ignore my technique and not criticize it enough.

MARIA: It seems like technique is something that you’re really focused on.

TINA: Yes, very much.

MARIA: How did you reconcile the fact that you had these anxieties, about making sure that you didn’t come across as too self-flattering, with the execution of good technique?

TINA: I think that, since the topic of my body had been such an insecurity to me, I almost wanted to make sure that my technique compensated for that. I wanted my technique to come out as powerfully as possible because I felt that the more my technique looked refined — unlike my body — the less people would be able to criticise it. I think that’s how I saw it.

MARIA: I think this problem is something that women artists — and not just visual artists, but also women writers, poets, musicians — face all the time. They’ve been called too precious, too self-indulgent, too self-flattering, as you put it. When women give away too much, they’re criticised for oversharing and being too feminine. Then, when they’re more careful with how much of themselves they put out there, they’re told they’re being too self-restrained and not artistically up to standard. To what extent do you hold yourself back in your art — not that you should because it looks meticulous — but I was wondering how much you feel that you must harness your own sentimentality and selfhood? At what point do you just go, “You know? F*** it, I’m just going to paint what I want, and say what I want, and be who I want in my own art”?

TINA: Oh, God, yes. This exhibition started off as a kind of therapy to me. Around two years ago, I suffered from body dysmorphia. It got to the point where I was just avoiding looking at my own image, whether it was in a mirror or a camera. Even when walking past shops, I wouldn’t look at the glass windows because I knew that I’d get upset. I spent a good five months just avoiding myself in any form, and then I started reading about this process called exposure therapy, which is basically about how when you overexpose yourself to something, you acquire it. I told myself, “Okay, I’m going to do that with my body”, and, for just under two years, I documented myself through photographs. I wanted to photograph myself in very uncomfortable positions, in my own space, in my own time. I’d study my anatomy, until I no longer remained scared of approaching a mirror because I’d have already seen myself at what I considered was my worst.

MARIA: It sounds like a process of reclaiming your own body and your image, on both a personal and artistic level, through the female nude — which, as an art form, essentially, has been in the hands of so many men for so many years. And by reclaiming that form, you’re also reclaiming your own identity, therapeutically. It’s such a wonderful and interesting dynamic.

TINA: Yes. I hate to say it, but I was in the position I was in because of something that a man had said to me about my body in a previous relationship, and it really frustrates me that I let him get to me like that. It’s messed up how the female body is always sexualised, and how certain types of bodies are treated badly in that regard.

MARIA: Yes, we’re always being looked at. What comes to mind is what the critic John Berger said in Ways of Seeing — how a woman, whatever she’s doing, whether she’s walking across the room or crying or being depicted in art, she’s always and inevitably looked at.

TINA: Yes. It’s just so unjust, isn’t it?

MARIA: Something else I would like to discuss with you in this regard is the mirror that you mentioned earlier, and which appears as a motif in your painting.

TINA: Yes, there are two that are mirror selfies. And then there are another two that show me getting more comfortable with myself. This is when I started allowing more people into my process — for example, my sister took photos of me. She took one of me sitting in front of my mirror, with the reflection behind me.

MARIA: Yes, that one is definitely one of my favourites from the exhibition.

TINA: As part of the process of getting to know my body for this exhibition, I spent a while looking at my reflection while walking over mirrors that I’d placed on the floor. I wanted to document the play of duality between myself and my suppressed feelings.

MARIA: It’s interesting how what you’re saying can also be described as an analogy for how we’re still in the process of reclaiming our own bodies and identity in art and in society at large; opening up to a diversity of representation. It’s such a powerful image: you walking on mirrors looking at yourself —

TINA: — and something I really regret not painting.

MARIA: Yes, I can see why that is. There is something deeply symbolic there, and, well, aren’t we all, in a way, walking on mirrors at this moment in time? As we said, we’re always being looked at, and it’s about time we returned the gaze and allowed a diversity of gazes, and representation in general, to enter into the picture. I know this is the cliched which-artists-do-you-look-up-to question, but I’m wondering who you were looking at as you were looking at yourself, as it were.

TINA: I mean, at the moment, there’s Jenny Saville who I love.

MARIA: I love Jenny Saville!

TINA: Her work is on another level of personal and intimate.

MARIA: Yes, I saw her work around three years ago at the All Too Human exhibition at the Tate Britain.

TINA: You were there?!

MARIA: Yes! Honestly, standing in front of a Saville is unlike anything. Her dimensions are just overwhelming — there’s this painting of hers titled Reverse that is actually a self-portrait showing a large-scale depiction of her face and I remember being so struck by it, I couldn’t move — I just felt inundated by the violence and extremity of its human-ness.

TINA: Yes! To me that’s something I want to do as well. I used to paint really small, like, A5 size, and used to think, “oh, it’s my quirky style”, you know? Then, one of my mentors in Barcelona told me, “your brushstroke is very expressive — trust me, paint big and you won’t regret it”, and he told me to look at Jenny Saville’s work and the moment I saw it I thought, “wow, this is so much more impactful!”. Ever since, I’ve wanted to paint big. Of course, you always get people saying you’re not going to sell if you paint big but that’s what I want to do. I feel like there’s so much more room for expression.

MARIA: This issue takes us back to the formalist aspects of the female nude. I was reading the other day about how Manet, with his Olympia, received the worst kind of backlash in his time, because of its disproportionate size. Critics called Olympia’s flesh putrid and were disgusted by it. I think when someone like Saville works in this tradition and blows it up to unprecedented proportions, it just makes everything hyper-expressive as you said. And like Saville’s, I think your brushstroke is too ardent to be restrained by size or any sense of propriety of form, and that’s exactly what marks your work with beauty.

TINA: That’s an observation I’ve really learned to appreciate. People see my work and say, “I’m starting to recognize you from your brushstroke”.

MARIA: I’ve noted that too! Your brushstroke is so unapologetic and wild and irreverent, in the best way possible. And bringing it back to what we were discussing at the very beginning of this conversation, like, why should it be restrained by a technique that is male-dominated and old and dying anyway?

TINA: Exactly! I feel like I’m in a very experimental phase. I’ve been doing this full time for two years. I don’t feel like I need a break or anything and I can’t wait to get back to it. I want to use different media — I’m very comfortable with oils, but I also like mixing charcoal into my work, so… yes, I just want to experiment right now. I also feel like it would be interesting to turn the lens on someone else now and document my relationship with them over a period of time, the same way I documented my own relationship with my body. I already have a person in mind — someone who I have a very weird and wonderful relationship with right now. I would love to explore that through painting.

MARIA: It’s interesting that now you’re going to, sort of, turn the lens away from your own self to navigate a relationship.

TINA: Yes, that’s exactly what I want to do.

MARIA: I’m so looking forward to everything you’ll come up with in the future, and I’m so happy for you and everything you’ve achieved, Tina, and that I got to see your work and talk to you about it.

TINA: I’m really happy that you accepted to do this as well.

MARIA: It’s been such a pleasure.