Wire Man

Skye Ferrante - the New York wire sculptor... unbroken until the final cut.

I wanted to be a lot of things growing up, but mostly a tap dancer, or if not that, then Robin Hood.

At what moment did you decide to be an artist, and how did you find your medium – wire.

No, sorry, there was no moment, no sudden flash of inspiration. I wanted to be a lot of things growing up, but mostly a tap dancer, or if not that, then Robin Hood. It was the twin influences of Fred Astaire and Errol Flynn. Even now, I regret not being either, although I did become a ballet dancer, professionally and, more recently, a fencing enthusiast. I have an art collector and friend, the Olympic sabre coach, Zoran Tulum, who gives me lessons as well as dollars in exchange for sculpture. It was Zoran who told me about Strait Street in Malta, how it was once the street of duels – for a time all duels took place in Strait Street. How strange to think of it, and horrifying: the centuries of blood spilled beneath the paving stones… although maybe less than what a generation of drunken sailors may have left behind.

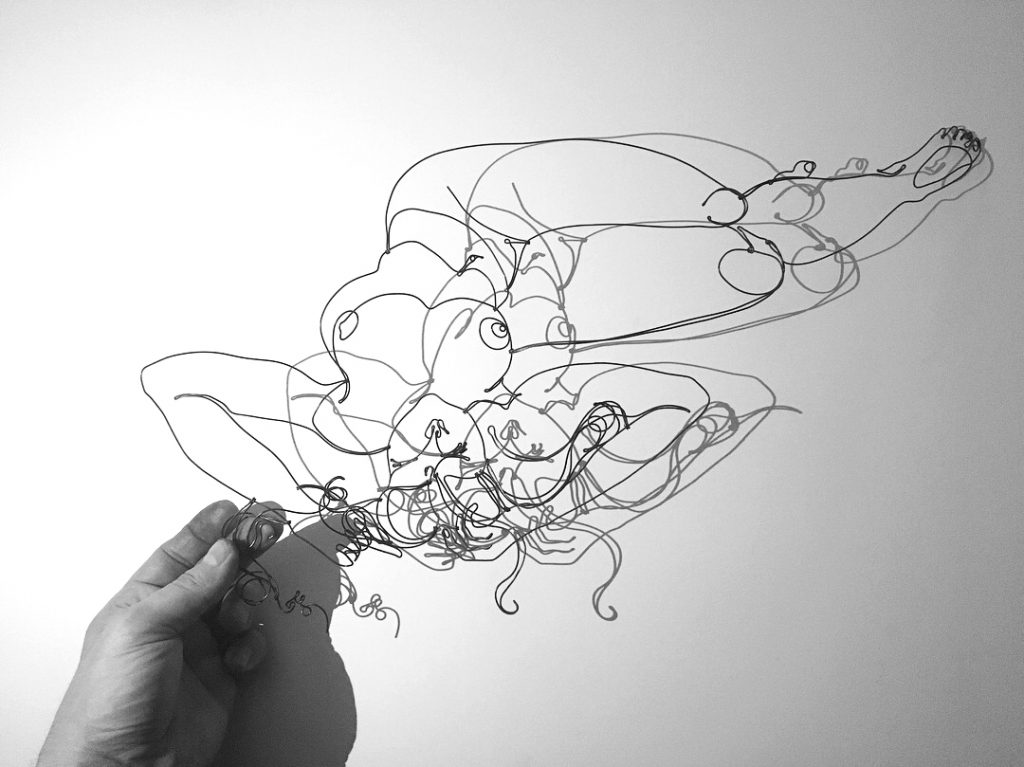

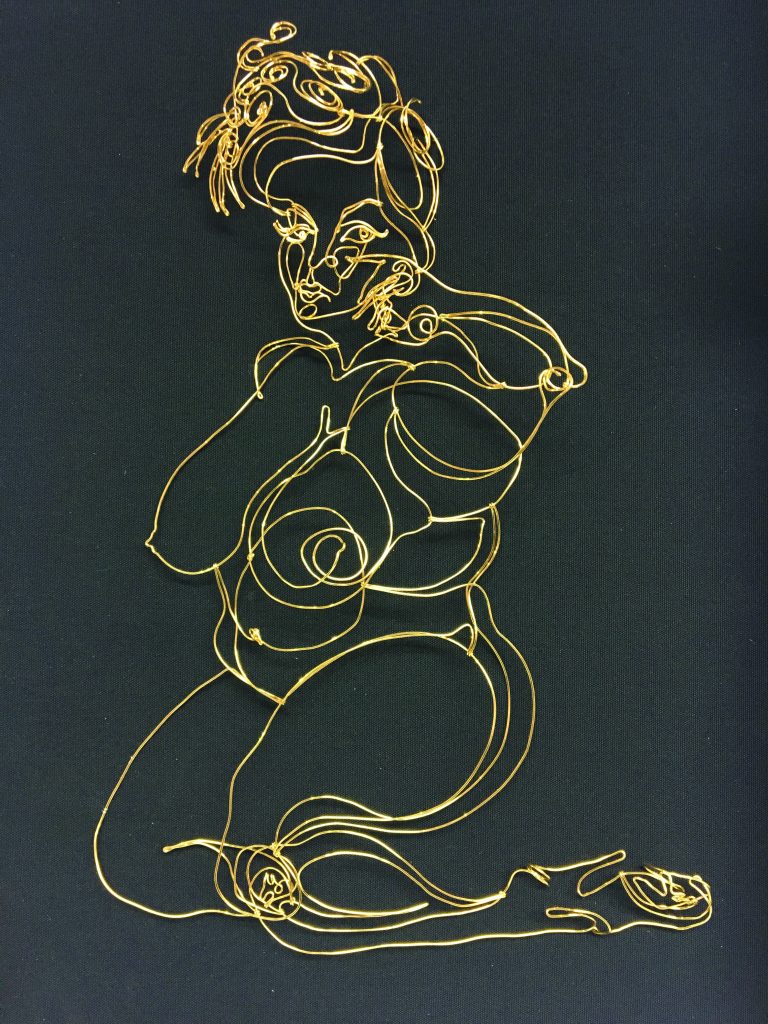

While recovering from a ballet injury I was apprenticed to a traditional bronze sculptor in his studio in the crypt beneath The Cathedral of St John the Divine in Manhattan. The process to reach a bronze was so time-consuming, laborious and ultimately expensive – from the armature wire to clay, to plaster cast, to rubber mould, to likely never affording the foundry fee while having destroyed the original artwork to make way for a series of unending reproductions – that I quit and tossed out every step but for the wire. I wanted to sculpt as fast as a painter paints and I found a way to do so, finishing each sculpture in one sitting, much like the impressionists I so admired, thereby capturing the movement that we see in life. It was movement that I was after, and this I credit to ballet, which informs everything I do. Art is movement – or rather, when it works, it moves. There is a continuity maintained in every good performance, whether it’s on stage or on the wall, to hold the audience. A good sentence will do the same. As with a good book, the pages turn.

How would you describe your technique?

I work, with no exceptions, from a single spool of wire – my only rule – unbroken until the final cut. I am self-taught. No art school, although if I had gone to one I would certainly have quit to travel instead. The technique continues to evolve – more recently becoming more illustrative than sculptural, with the influence of my daughter, who draws very well – much better than me. She can draw or paint exactly what she sees in front of her, from a photograph or a painting in a museum.

I only have three hours of strength and focus to bend metal and make the connections that I need to think continuously, in the present, often two or three steps ahead. With less time, and the pressure of human presence while respecting theirs, I think less, move faster – as fast as I can without losing any skill. The result, when viewed from the model and the audience’s point of view, is performative, including flourishes, spinning pliers, twisting flicks of the hand, pirouettes of the wrist and elongations of the arm – a ballet dancer in a sword fight.

What do you do for inspiration to create art? And what has been the most challenging work you have created?

“Inspiration is for amateurs,” Chuck Close said. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.” I couldn’t say it better myself, but I’ll add to it. I am not inspired – period – until the moment I begin. I almost never want to sculpt until the curtain rises or, in this case, the robe falls.

I’ve had portrait sittings booked for weeks, and with the most extraordinary people – but I dread it, always, until the first bend. I’d much prefer the company without having to go to work. It’s exhausting, and I usually collapse at the end. At least there’s wine. The people who sit for me are why I sculpt, and ever since I began writing about the process and the models who are my friends, I stopped choosing as the sculptor. I choose people I want to write about and the sculpture is the excuse – it has become secondary – although it pays the rent… inspiring me to breath another month of New York air.

If you mean the most technically complex and/or exhausting I would say a three-metre, free-standing Eiffel Tower I completed in one shot, one spool, over 10 days in my London studio, using over 340 metres of continuous aluminium wire which, coincidentally, if stretched up from the ground would reach the top of the real one in the Champs de Mars.

Would you agree that your favoured topic is the female nude?

I do love trees as well, and florals especially but, yes, I would agree. It all goes back to ballet. I was the only boy in a room, pretty much, until I attended S.A.B. where I was shocked to be in a room full of men – and no women at all, and the teachers were men too – and Russian, except for one Dane.

I can’t say I’ve ever been too comfortable with men, either as my subjects or my friends, with few exceptions, but for a long time, male nudes were my bread and butter. People are people, and yet… female nudes are much more challenging. I can make mistakes on a male nude, hide them in the rough lines and it will still work. Soft lines show everything, curves rather than angles, and I love all of them on a woman. The model makes a difference. I don’t have types or any real preferences, except that they be aware of themselves, as dancers are, although they don’t have to be dancers – only present and not too stiff.

Even in the worst cases, when we are not on the same page, I try to finish what we’ve started and I’ve been surprised by the result. In the best, the model and I are collaborating, dancing in a pas de deux, and probably laughing, and in her I find an infinity of lines and potential sculptures and I’m a little bit in love. She’s not my ‘muse’, the term is outdated and applies to a non-speaking role and the object of a problematic Greek myth. She is a partner in the process and, certainly in my experience, Galatea speaks. When I get lucky, she tells me a story – and if the sculpture’s good, I’d like to think that the story resides in it.

How do you think New York has shaped your creativity, lifestyle and outlook?

New York could be kinder. New York has been kinder – but there’s no other place like it, unfortunately, and I’m biased. I was born on 5th Avenue and 105th Street. If I ever wanted to run home, I’m here. So I flee – to Europe, mainly.

You spend a lot of time in London. From your perspective, how would you describe the artistic art scene there?

London is a second home, long before my unexpected living from sculpture. I arrived there in the early nineties, as a writer. I can only describe the art scene then as sickeningly trendy and very small. It’s still trendy, still sickening and, if you judge by the expansion of Central Saint Martin’s in King’s Cross, it’s superfluous and big business.

I think London trends have been informing New York for some decades now. If there was ever a London or New York scene you wouldn’t know it, because the contemporary art world is now viewed in giant tented cubicles the world over, and shared seasonally like fashion. I enjoy going to the museums in London, most recently with my daughter, often to see one artwork and then escape to the nearest park – in the case of Kenwood House, you can see the best Vermeer and the best Rembrandt in the world without ever leaving Hampstead Heath.

In any given art fair, by contrast, we are exposed to a shopping mall experience of art and the latest fashion trends of shiny or bright things and larger than life, machine-fabricated creations, made to fit on very small screens. No thanks. I’d rather fly a kite on Parliament Hill.

You’ve been to Malta. What are your thoughts on its potential as an art destination and what have you experienced there?

I’ll tell you what I think of Malta as a potential art destination, honestly. I think it has more potential than Athens, and I know Athens well. I speak of Athens because I believe Athens is the new Berlin – but even when artists were rushing to Berlin for cheap space, I couldn’t see the point. The buyers aren’t there. They still aren’t. The buyers are in New York and London, full stop. I lived in Paris. Great place to live, to make art, to make love, but not to sell – and to sell is to live.

Malta is experiencing a construction boom, at least for the next few years, and with every new apartment there are walls to fill. Malta has buyers, they just don’t know it yet. Malta really doesn’t need art galleries to make it an art destination either. Galleries are passé, along with fixed locations and annual rents. All we need are collectors and dealers to refer them to our studios or to their homes where art can be loaned on approval. Yeah, I could keep a studio in Sliema – as long as I don’t have to drive in that traffic! Free water taxis for artists? I’m in.

What are you working on now?

A book. A working artist memoir called The Naked and the Nude. It’s a collection of portrait stories about the wild and fabulous and beautiful people I have had the pleasure of sculpting.

What’s your philosophy on life?

Parry riposte.

Skye Ferrante is represented by Lily Agius Gallery in Malta. www.lilyagiusgallery.com