If God was an Octopus

... and other stories from the artist from Fgura who moved to Los Angeles

Adrian Abela is, in my opinion, the master of perspective. A visual poet. In simple words, he is a skilled and brilliant interpreter, able to communicate what makes the Maltese, and people in general, tick. And what should make them tick but doesn’t.

Abela Performs quasi miracles in his skill at removing filters and inventing, applying or discovering others. His work is a testament to his being so in tune with our collective consciousness it almost seems omnipotent at times. It is almost as though he can see and explore extra dimensions. To my knowledge, there are very few people as capable as Abela at exploring the fantastical aspects of the intricate web, which is Malta’s ‘culture’. It is almost impossible to interpret his worldview better than he does himself – and in this, he takes on the epitome of the role of the artist.

Abela studied architecture and civil engineering in Malta and Milan, then moved to California to study for an MFA in sculpture at UCLA. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

On trying to analyse his work, one almost feels as though Abela can transport his mind to inhabit ‘god’s overseeing eye and sees the earth in a crystal ball of sorts – zooming in and out of the most intimate details that make up anthropological systems across time. It’s as though he can zoom in and out with his fingers and study why what is what, and when it happened – while understanding that even if he did have this crystal ball to play with, he might still be far off or outright wrong. In my mind, this skill results in mesmerising interpretations and interpretations that are not necessarily everyone’s cup of tea. It takes a lot of discipline to make extra-terrestrial, extra-national, extra-social, and extra-corporeal observations. To shed all constraints taught by time spent in society while studying, interpreting and criticising this same society.

He applied what is probably a lot of effort to answer the most pressing questions in his mind. In the mind of the average Maltese boy – questions such as what is this God everyone is so obsessed with? Why do we spend money on looking for this black oil but not on saving drowning people? Why do we award citizenship to machines and not to our brothers? Why do the people pretend they can’t control the sprawl of concrete as if it were alive and proper weed? Why do we think we’re special?

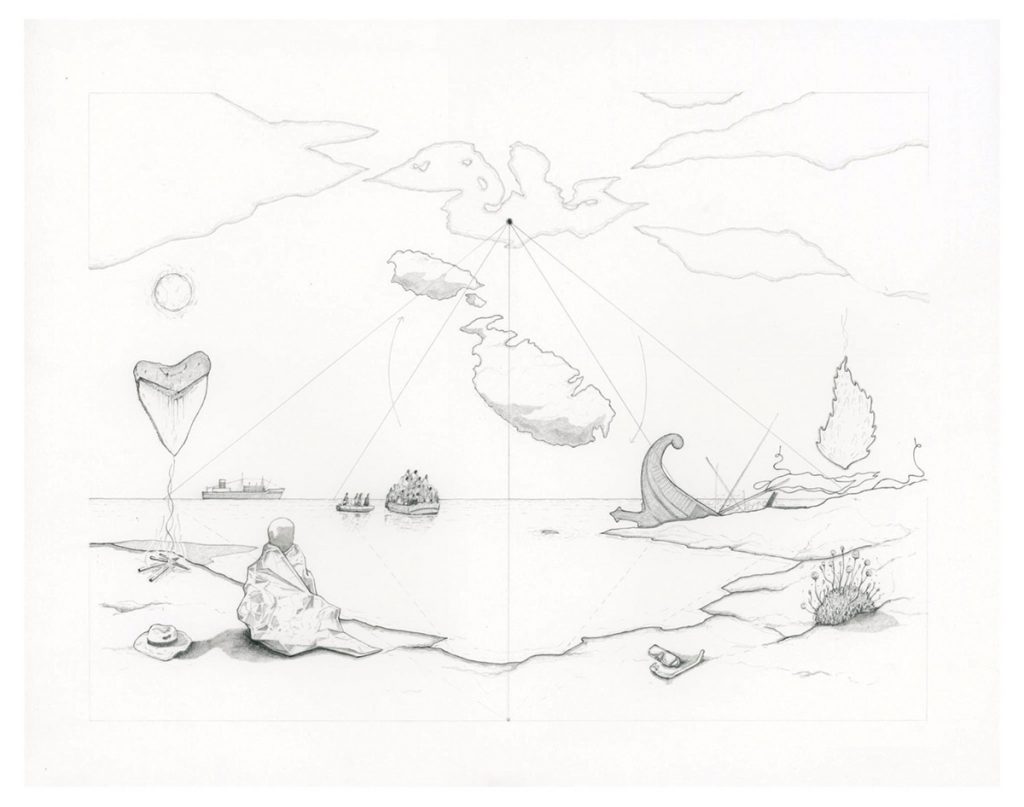

“I am aware that my work is very much influenced by growing up Catholic in a post-independence state searching for its identity. Growing up, I was very aware of the close marriage between organised religion, or so-called spirituality and politics. Later on, the Maltese government itself, on one occasion, convinced the population to invest unheard of amounts of tax money at the time in oil exploration by calling the well ‘Madonna of the Oil’, as if the newfound wealth was a miracle. In my sculptural work, I attempt to explore the parallels and contradictions with African Migration to Continental Europe through Maltese territorial waters.”

The work Il-Madonna taz-zejt explored the bizarrely maliciously over-funded oil exploration efforts when compared to search and rescue efforts in Maltese territorial waters. Oil symbolism is everywhere – large black round paintings, with subtle iridescent paint details of maps and depictions of boats laden with the desperate which are about to capsize and those on it drown and perish in the darkness and the silence.

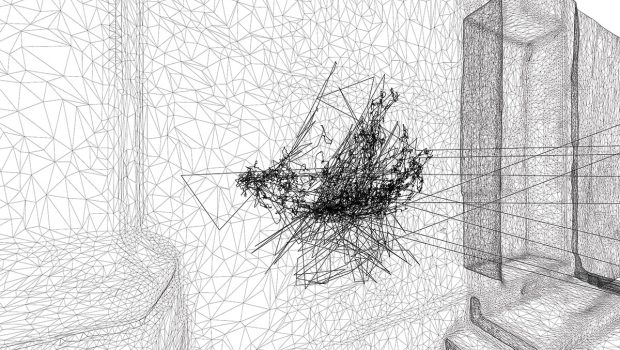

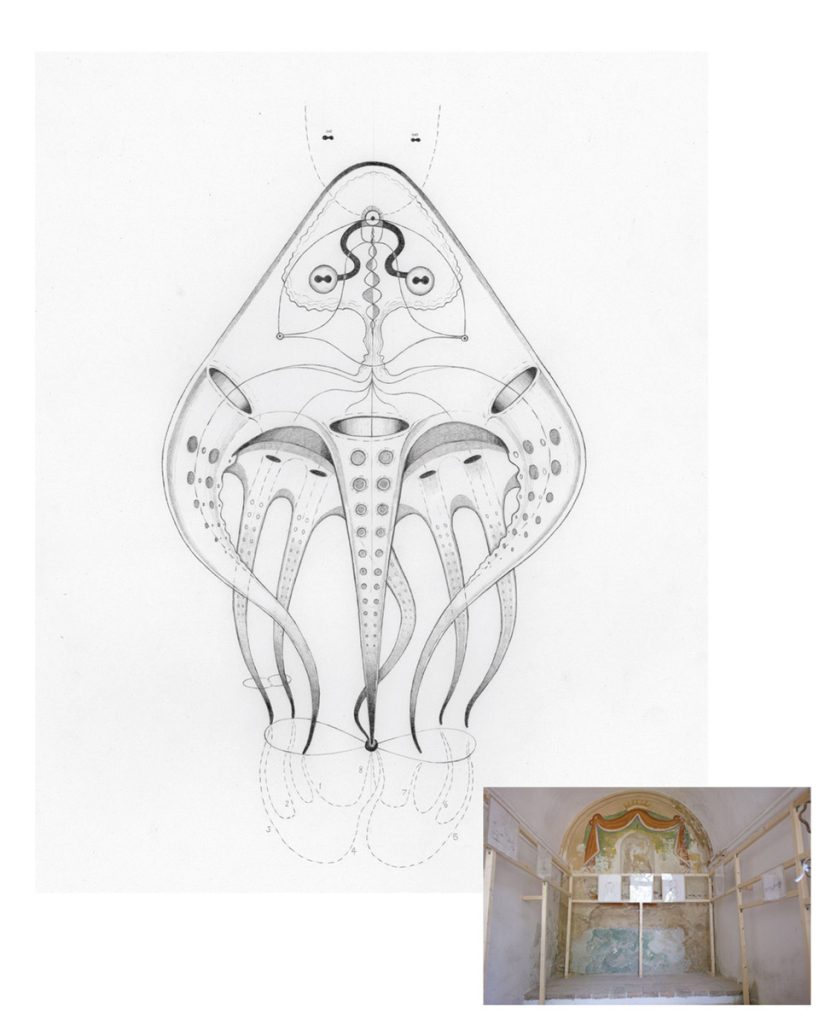

The work Baħar, which was shown as part of last year’s Mediterranea 19 Young Artists Biennale, reimagined God as an octopus, or octopi or, rather, proposed the octopus as a map for perceiving reality.

“The octopus is presented as a model for creation/consciousness and proposes a framework from which we can interact with the world. Mirrored in the neuronal distribution of the octopus, Malta is being presented as the first limb to self-realise its position in the system, turning revelation into political action. The drawings were produced to accompany a series of lectures and performances, which were unable to be held due to the pandemic. One of these performances was called Declaration of Dependence. ‘

The octopus features in drawings, illustrations, and reinterpretations of religious symbols. Many are reminiscent of the overwhelming display of religious memorabilia that would have adorned the walls throughout Abela’s childhood. Marble Tombstones feature paintings from actual photos of some of those buried at Malta’s most mystical cemetery – but the faces sport tentacles. The case is made with spiritual and metaphysical evidence – scientific and architectural drawings prove to the gullible that it is just as likely that God was an octopus.

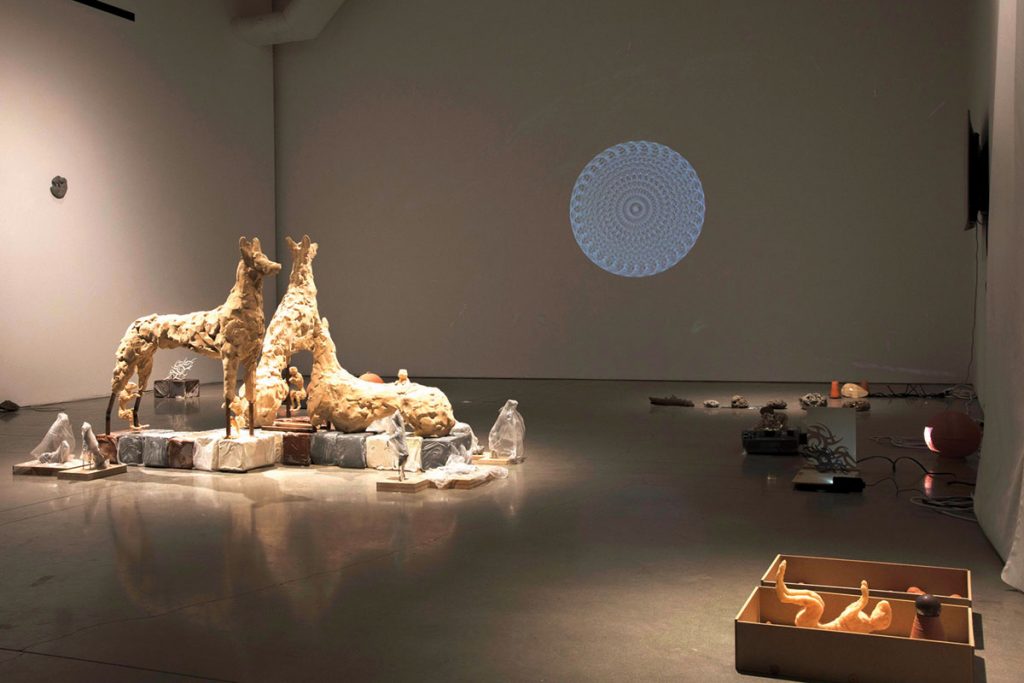

In the group show at Malta Contemporary Art (MCA) in 2018, Desert Island, curated by Mark Mangion, through his work Department for Martian Transportation, Abela is melancholic about the rape of the rock (being both Malta and planet earth) on which he was born, the ravaging of its landscape and the nonsensical greed of its inhabitants.

“On the island in the Mediterranean Sea where past lives grow as buildings, where no minerals and no water exist anymore, (some) humans found a way to sell nationalities for rhizomes to go to the continent.”

In this show, his sculptural installations look somewhat like a small expo of different harvests – harvests of souls, physical and metaphysical resources. The yield of a nation desperate to prove that despite being resource-less, with some imagination, and ruthless disregard for beauty, one can always find ways to profit.

FOREWOR(L)D was the solo show Abela had in LA at Make Room Gallery. He took inspiration from a plaster mould he made of wall etchings/graffiti taken from a limestone wall on the Laferla cross. From here, he could look down and observe life. Abela contemplates the legal issues governing the rights or, lack thereof, of a person to inhabit a particular corner of the planet.

“Current political discourse draws you to think about surfaces, edges, and identities. Holding the panel from the wall that was watching over the edge of land that I am identified by in all government documents feels unreal, not many can go on a hill and see the perimeter of the parameters of what others identify them by. To see the boundary for your privileges and responsibilities by standing on a spot and rotating 360 degrees.”

If art is the foremost diplomatic tool – Abela would make a stellar ambassador for anything Maltese, whatever that may mean.

Abela is the kind of artist whose work pays tribute to the art consumer’s intellect, unlike many Malta based so-called artists who pretty much insult the audience’s level of comprehension. Despite all efforts to brainwash him to accept and conform, he questions and forces the audience to do the same.

When I see his work, it’s as if I exhale. I understand that understanding is not vital. I reconcile with the humility that comes with accepting the existence of realms and dimensions we will never be able to see. Of anything we cannot and will never understand.

So, what’s next?

“I am most excited currently about a series of paintings and clothing which I had started in 2015 and continued exploring in Gozo during my visit this year; hopefully, I could spend some months there in 2023. I am also spending time on growing ‘Church End State’, which is my non-art practice that helps me fund some of my art by selling functional and non-functional objects. I have been helping college artists with Public Artworks in the US and proposing some of my own too. I am publishing an essay about art and labour with some paintings at an Auto Body Shop later this year and keeping up with my practice at the studio. I also wish I could give the Declaration of Dependence lectures in Malta someday and be more involved with the community there because I feel like there is so much potential that is unseen or wilfully ignored. Work from the show as part of the Mediterranean Biannual for young artists School of Waters in San Marino will also be shown in Naples in June of this year. Baħar will be shown on the island of Procida, which is this year Italy’s capital of culture.”

And I cannot wait to experience what he prophesizes to conjure next.