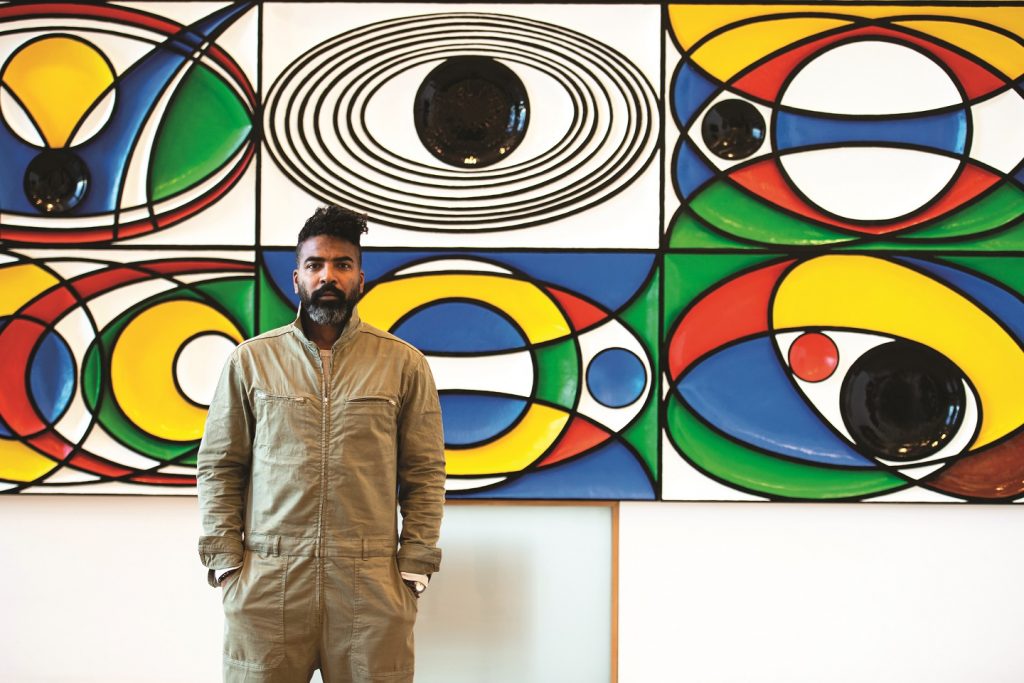

Consented Subversion – Graeme Mortimer Evelyn and the conversational power of art

Ann Dingli interviews artist Graeme Mortimer Evelyn, discussing his methodology of subversion, as well as a recent visit to Malta that crystallised his views on the role of contemporary art in historic contexts.

Graeme Mortimer Evelyn is a hybrid artist – musician by default, visual artist by vocation, researcher by instinct. Based primarily in London, his experience and portfolio are vast, his work having been patronised by institutions of both secular and holy grandeur. Commissioners have included the Gloucester Cathedral, the Royal Commonwealth Society, The Royal Collection Trust and Kensington Palace, amongst several others.

The path to Evelyn’s currently practice has been circuitous. He is most known for his sculptural work, but his practice is encased by divergent tangents. Growing up, his business-owning parents encouraged him to study marketing, which he did. He later gave in to a nagging artistic call, following a Graphic Fine Arts course at Anglia Ruskin Art School in Cambridge with a focus on printmaking. After that, without adequate etching presses or equipment to hand, Evelyn turned to drawing and sculpture. Performance art, poetry reading and performing as an international circus clown ensued – all against the constant backdrop of music-making.

In the art world, he is now mostly linked with his multi-media interventions inside municipal buildings, often large-scale and permanent, which he describes as statements of subversion within deeply entrenched narratives, rituals and histories. “I go into institutions and I subvert them, with their consent,” he explains, describing his overriding process, but speaking mainly in reference to his sculptural work for religious institutions. “They know upfront that I’m going to take the most important tenet of their institution and subvert the message in order, not to undermine, but to bring in and excite a new audience.”

This approach of provocation is bolstered by research. Evelyn describes immersing himself into given contexts and communities in order to fully grasp the lineage of their rituals and messages. “I like to get embedded into the fabric of the institution – you know, you make friendships, you see their battles, you understand where they are coming from and then it enriches and informs the research even more”. His position is particular, belonging to the Buddhist faith yet working for patrons including the Church of England. As an outsider, objectivity is more achievable.

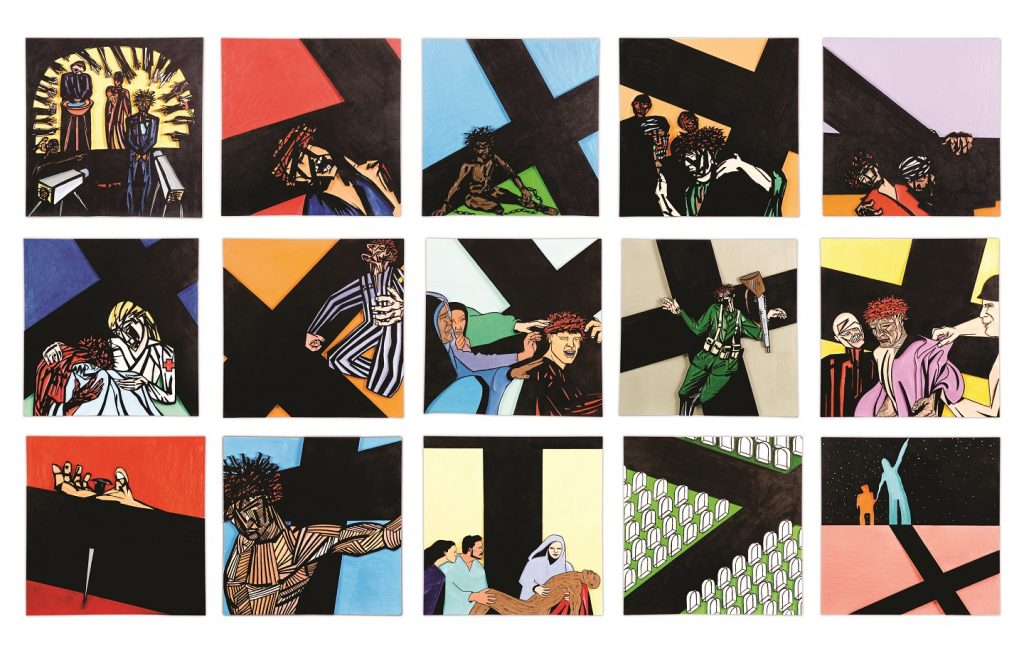

“When I did the Stations of the Cross for Gloucester Cathedral, my pitch to the Dean was that I’m a practising Buddhist, but I would like to make the Stations accessible to atheists, by subverting the Christian message,” he explains, describing his work around the stalwart art historical and biblical subject, exhibited at Gloucester Cathedral Cloisters during the period of Lent 2006 in 2007. “I wanted to stretch it apart and make it a human journey of the cross by adding another station of my own – a secular audience would then be interested in that, whilst at the same time recognising the subversion”.

“It’s about making the artist become the bridge builder, rather than an instigator,” he continues, the conversation stretching to his work on Reconciliation Reredos, which is on permanent display at St Stephen’s Church in Bristol, one of the city’s oldest churches, located in its Medieval centre. Established in the 13th century and historically significant as the city harbor church that blessed every Bristol merchant slave ship from the 17th to 19th century, before setting sail on their voyage to the West African coasts. The Reconciliation Reredos was designed to be a contemporary artwork of universal reconciliation, responding to the church’s past, reflecting the voices of Bristol today, whilst representing the potential of the future. It remains the only permanent public artwork within the UK created to address the tragedy and legacy of the British Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Evelyn’s recently completed public artwork entitled The Eternal Engine, was commissioned by a Diocese of London and unveiled in November 2017 for the only church built in the capital in over 50 years – St Francis Church in Hale Village, Tottenham. The artwork is currently the largest permanent, hand carved and painted contemporary altarpiece in Europe (5m x 3.5m, weighing over half a tonne). The site of the new church is situated adjacent to where Mark Duggan, a young black man, was fatally shot by armed police in 2011, triggering city-wide riots. The Diocese of London chose that site to establish a missionary as part of London’s healing process. Evelyn’s brief was “to create a new image of God without representation, that reveals the individual and the community’s relationship to the Creator”.

For Evelyn, it was important that the function of the work engaged and involved the diverse community from the area, transferring ownership over the artwork to the people as a permanent reflection of their unique history and creative legacy. When first unveiled, the reredos was the largest contemporary altarpiece in the UK, inviting contemplation from new audiences not just by virtue of its subject and execution, but also through its sheer physical scope.

“The bridge building role is not only a way to introduce new audiences to something they might have previously disliked, but it also demonstrates the power of art”. This classification of art as a potent mode of communication coloured Evelyn’s last holiday before lockdown, which happened to be to Malta.

“I got a lot from my visit to Malta – I was so inspired by what I saw there. I went out of my way to find contemporary spaces. Because there’s great architecture, so I thought: there’s got to be some contemporary art here. But what I did notice was a separation. I saw some incredible stuff in Malta’s churches, and I wondered whether there was an opportunity for contemporary artists to use this to their advantage, to bring in new audiences”.

“When I visited St John’s Co-Cathedral, for example, which is super Baroque bling, the ideas that came to mind… all the tiles on the floor, the creatures drawn in a very contemporary way, the patterns that are used – there are so many ways contemporary artists could reinterpret that history. Even if you are a rabid secularist, you can still use that”.

For Evelyn, the trip was a catalysing experience, fueling ideas for his next research and interpretive experiments. “I intensely documented [what I could] about Maltese visual culture – built environment, fauna, and the islands’ religious and historical sites have given me wealth of visual content to work with. So with that, I am currently focusing on creating a new body of work which will include drawings, mixed media works on paper and relief sculpture based on my response to Malta’s unique cultural landscape”.

Evelyn’s objective as he moves into a post-Covid world of art practice, is to channel his unique experience as an artist into the discussion around democratisation of public space and cultural cohesion. “I’m presently working in consultation with Office for the Mayor of Bristol in the UK, helping to inform future visual responses to public monuments in Bristol following the removal of the statue of Edward Colston, which was brought down by protestors in summer 2020”. As ever, Evelyn is still making music in and around his visual art practice, and along with his work tied to Bristol and Malta, he is also currently collaborating with dubstep artist MALA to create immersive sound and visual sanctuaries.