Where are the angry birds?

Art and Gender Based Violence

I am sick of seeing ‘artists’ paint flowers.

I am sick of seeing ‘artists’ paint landscapes.

I am sick of seeing ‘artists’ make art about discovering who they are, about their identity this and identity that…

And I am sick of not seeing enough anger and angry, sexual violence, and bloody victims and degraded, helpless, desperate, abused limp figures in the works of artists in Malta. Of course, it’s not up to me, or to anyone else to tell artists what to do, but the lack of reflections on frustrating realities by the local artistic community and the absence of reactions explosive or not, to social ills is astounding.

Malta is full of invisible women. Women who have to hide their pregnancies when they have foetuses growing inside them. Women who have to travel to have terminations which will save their life. Women who were deprived of financial independence because society expected them to stay home, clean, and paint flowers.

Women who are trapped, are invisible to the police and to justice, women who suffer physical and emotional abuse and cannot run away because neither the geography nor the tongues of their mothers, would allow it. Trapped until death – whether this comes by way of murder, or old age.

So they paint landscapes. Or oranges. Or orchids. As do their sisters. To calm down.

Art has constituted the megaphone of important messages turned to the entire society, a vessel and tool for expression and rebellion against a male dominant.

I asked Maria Louisa Liotta Catrambone, a criminologist with extensive hands–on experience with a human rights NGO,to give us the low–down on the statistics.

A 2018 analysis of prevalence data from 2000-2018 across 161 countries and areas, conducted by WHO on behalf of the UN Interagency working group on violence against women, found that worldwide, nearly 1 in 3 of women have been subjected to intimate partner violence (marital rape, femicide), sexual violence and harassment (rape, forced sexual acts, unwanted sexual advances, child sexual abuse, forced marriage), human trafficking (slavery, sexual exploitation), female genital mutilation and child marriage.

A number that however increases if we consider, and we can’t not do it, emotional and psychological abuse, street harassment, stalking and cyber-harassment. Even when there is no physical violence, abusive language or actions can be very damaging.

Violence against women and girls is a human rights violation that continues to be an obstacle to achieving equality, development, and peace. The immediate and long-term physical, sexual, and mental consequences for women and girls can be devastating, including death.

Malta remembers the tragic horror of femicide through the names of its victims – Mary Saliba, Rose Casaletto, Angela Debono, Carmen Micallef, Gemma Fonk, Diane Gerada, Sylvia King, Jane Vella, Maria Buhagiar, Vanessa Grech and her 17 month old daughter Ailey, Rachel Muscat, Pauline Tanti, Josette Scicluna, Patricia Attard, Doris Schembri, Lyudmila Nykytiuk, Theresa Vella, Caroline Magri, Eleanor Mangion, Maria Carmela Fenech, Antonia Micallef, Shannon Mak, Yvette Gajda, Margaret Mifsud, Charlene Farrugia, Meryem Bugeja, Silvana Muscat, Catherine Agius, Paulina Dembraska, Christine Sammut, Irena Abadzhieva, Karen Cheatle, Lourdes Agius, Marija Lourdes, Daphne Caruana Galizia, Angele Bonnici, Chantelle Chetcuti, Rita Ellul, and Bernice Cassar.

These are the names of the women killed, at the hands of a man since 1978 in Malta.

But there is no corner of the world where women do not suffer any kind of violence, the latitude does not save anyone. Even more complicated is the situation of the migrant women forced to suffer unspeakable violence in refugee camps and during their dangerous migration routes. With MOAS-Migrant Offshore Aid Station, the international humanitarian organization founded in 2013 in response to the Mediterranean maritime migration phenomenon and now dedicated to providing humanitarian aid and services to the most vulnerable people around the world, we have been direct witnesses. We have seen with our own eyes the physical and psychological wounds of women who, after spending terrible months in Libya, risked losing their lives at sea. We have heard the stories of the cruelties inflicted on Rohingya women fleeing Myanmar. And we continue to witness the violence committed in the conflict in Ukraine.

In this context the voice of women plays a very important role. Among the various instruments of protest and emancipation, art has constituted the megaphone of important messages turned to the entire society, a vessel and tool for expression and rebellion against a male dominant.

From Artemisia Gentileschi in the 1600s to Cecilia Beaux two centuries later, from Georgia Okeef to Frida Kahlo, from Clara Peet to Khathe Kollwitz, all these women have fixed in their works a representation of the female voice, a vision of the world shaped by them.

Today, in the increasingly integrated system of the art of fashion and design, we can hear the voice of women for issues of great social and political importance such as those of women inclusiveness, equity, and social and cultural rights from women artists. The issues of gender difference represented by the Kenyan Ato Malinda, the prejudices on the body of the black woman by the South African Mary Sibande, and the the sexual discrimination represented by the South African Stephanie “Kenyaa” Mzee, are precious contributions that enrich the path towards gender equality and the eradication of violence against women.

What about the local scene? What are malta based artists’ reactions to vicious murders and the delays or ineffective judicial procedures which follow them? I tried to recall the instances when artists reacted.

When it comes to theatre and performing arts, I must admit we have seen some realistic, visceral reactions to gender based violence. In 2013 TAC theatre staged Kenyetta Lethridge’s play Innocent Flesh with in your face interpretations of the realities of various forms of abuse, will last month 4Jays Theatre and actors Shaian Debono and Aleandro Bartolo staged Vjola, a play on domestic violence to coincide with The International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

The work Grace | Rofflu staged in 2009 by the Rubberbodies Collective and directed by Jimmy Grima was very powerful and explored a relationship which meandered from love to violence using dance and physical theatre.

Experimental theatre in Malta also saw the launch of Alice in Wonderless Land, DIY Theatre by Teatru Malta for ŻiguŻajg 2020 which explores and highlights the impact of a patriarchal society and is designed to be set up in schools to hopefully inspire teenagers to break away from the shackles of their predecessors.

Teatru Malta also staged Laringa Mekkanika (A Clockwork Orange) in 2019 – adapting a classic dark and violent tale for a teenage audience, hoping to spur discussion amidst the rising cases of reported psychological problems in these age groups, with increasing incidence of self-harm perhaps coinciding with increased exposure to a more easily available relentless bombardment with violent narratives and imagery on social media and the internet.

A simple internet search reveals a poor response to gender based violence and rape locally and one comes across a few exhibitions and works of visual arts with victimization rather than anger. And dreams of atonement rather than a call for change.

The National Commission for the Promotion of Equality organized a show for the Valletta 2018 capital of culture entitled ‘Domestic violence portrayed in original art creations’ by artist Raymond Darmanin. The works portray dreamy, floaty women escaping. No anger. No blood. No violence. The message seems to be Run Woman Run with no allusion to fury directed towards the perpetrator. We seem to be saying – Let’s not dwell on the reason for your pain. Or the mention of pain at all.

Another image which pops up is of a painting with the title The Rape of Prosperina who taking after the famous marble statue by Bernini is romanticized in work by Luca Azzopardi. Both Bernini and Azzopardi seem to want whoever looks at the image to be aroused and not infuriated.

The Catholic Church in Malta sponsored an exhibition with the Jean Anthide foundation titled (Un)silenced: celebration of self-determination, solidarity and liberation – Archdiocese of Malta and once again the focus is on the victim. No mention of a perpetrator. Artist Carol Zammit – one of the artists in the show actually shows some anger but the rest is more flowers and landscapes – the take home lesson here seems to be, take a deep breath, forgive him, forget about him. Rebuild your life. Be a silent warrior. Carry your rapists child to date. Don’t bother about your shared assets, better poor and free than secure and trapped. Paint some more grass moving in the wind with little tiny flowers. It’s calming.

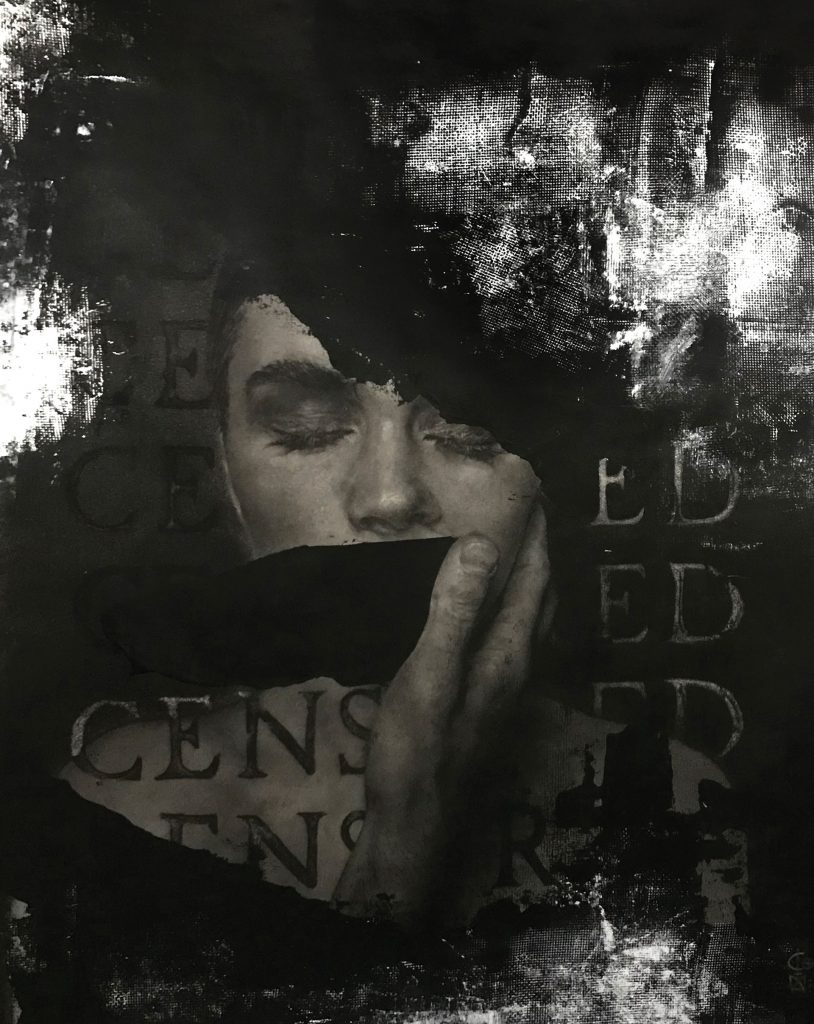

But there are also many visual artists who are finally showing their anger and frustration. CO-MA has been creating powerful, manipulated, hyper-realistic charcoal drawings which are evocative and angry and dark. The mostly female subjects are being silenced and blind folded and they look furious and beautifully deranged.

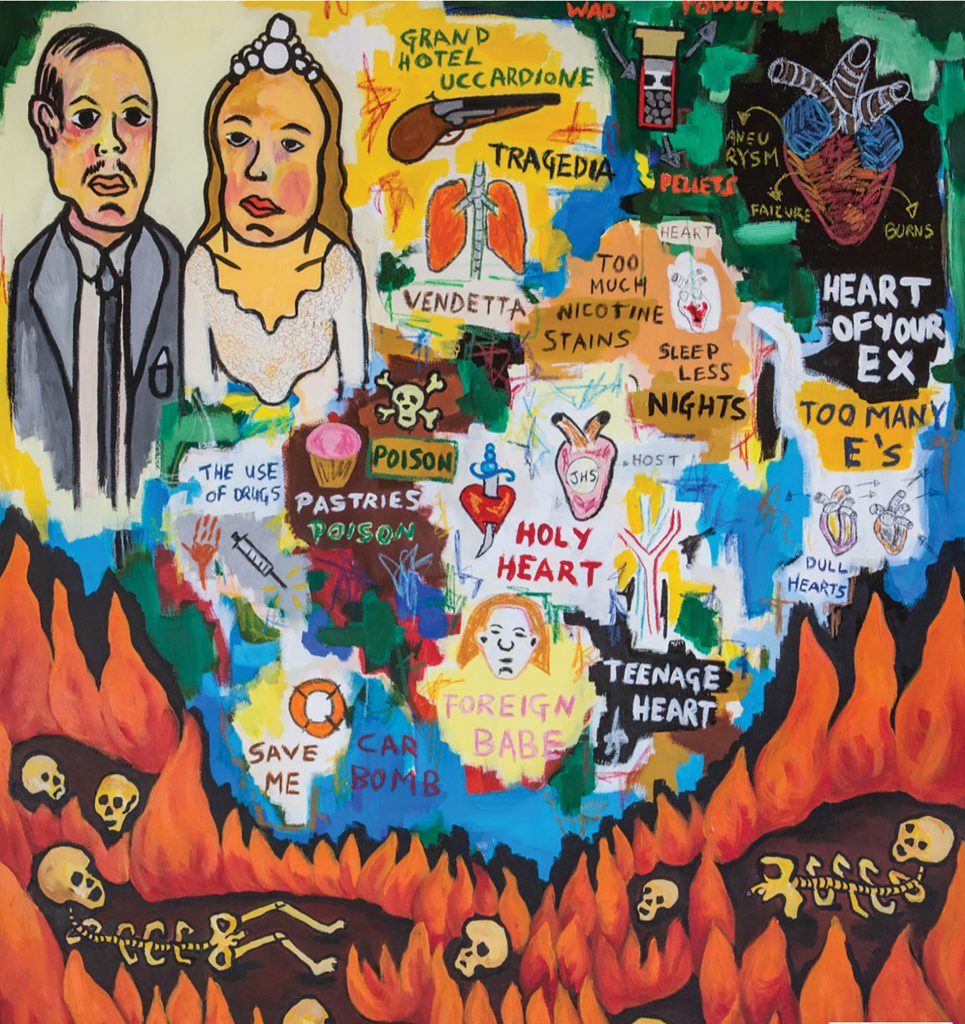

Ryan Falzon’s local show We Lost The War (2017), in Berlin under the name Fritz ist Amerikanish (2020), was more about political violence, ideology, terrorism and organized crime, rather than gender based or domestic violence. But it’s angry. And anger at the systems which permit any form of institutionalized violence should be brought to light and criticised.

Charlie Chauchi’s show Sheherazade at Valletta Contemporary in 2019 revolved around depictions of abuse, debauchery, beauty and brutality in the Maltese-run soho clubs and brothels in the late half of the 20th century. The installation is immersive, velvety but provocative with confusing plays on words and nude women who vanish as you walk by them.

Artist Charlene Galea recently performed in the work titled Her Mum’s Clothes in Vienna, based on the true story of 4 mothers and the relationship with their daughters, where one of the women is forced into prostitution and violently abused by her husband. The actresses wore the actual, now deceased victim’s red coat.

But possible the most powerful works seen recently which deal with the ever present reality of gender-based violence are those by Rachelle Deguara and Emma Attard.

Rachelle’s most recent work is a text-based site-specific performance called No Place Like Home. It was part of the emerging artists’ exhibition at Spazju Kreattiv, curated by Trevor Borg and supported by Agenzija Zagħzagħ, called Shifting Context II.

The artist borrows the stories of previous femicides in Malta and interpreters them, switching the gender to emphasize how society has become desensitized to cases of violence against women. Subverting the dominant mythology of the feminine as submissive, the text explores the tensions between the themes of power and subservience, constraint and liberation, subjugation and empowerment.

Her first debut performance installation was during the exhibition Debatable Lands. The artist did a performative intervention about four women who were killed because of systematic failure, and she was preparing for a protest. The sound installation narrated the stories of Daphne Caruana Galizia, Kim Borg Virtu, Miriam Pace, and Chantelle Chetcuti.

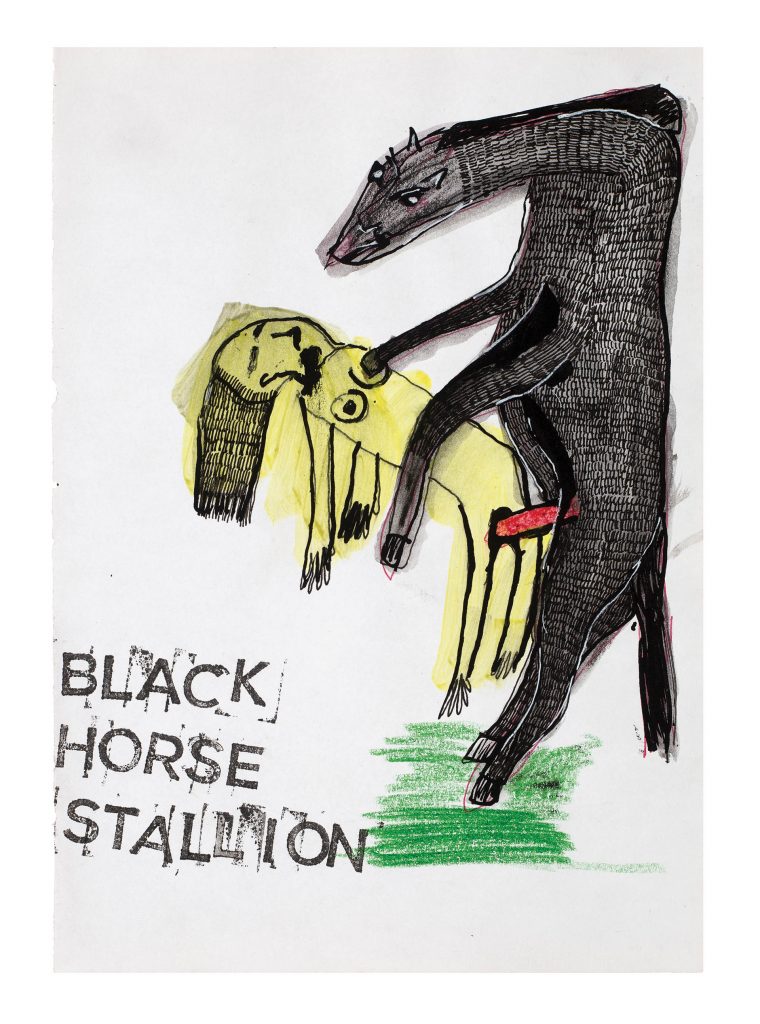

Emma Attard uses art as a tool to therapeutically scream and externalise the rawness of her experiences, rendering trauma concrete so that it can be released. The work exhibited at the exhibition Groundwaters, curated by Gabriel Zammit at Valletta Contemporary are literally drawings ripped out of her sketchbook. They speak of the unspeakable, blowing the viewer away with their intense simplicity, dripping with fury.

Emma Attard’s drawings were, perhaps originally not meant to be seen but as Gabriel says ‘Ultimately her work typifies the aesthetic transformation of pain into emancipatory potential and as viewers, if we can get past the gut punch and the uncomfortable pull of looking at someone else’s tragedy, what is left is a fragment of utopian potential, which is indicative of the art’s power to merge the real and the imaginary in the pursuit of catharsis.’