Practice, Patience, Perseverance

Introducing Salvu Scerri – one of Malta’s first graphic designers

‘Practice, patience, perseverance’ – a resolute mantra Salvu Scerri lived by in his personal life and career as, possibly, one of Malta’s first known modern graphic designers. Scerri, born in Floriana on 22 February 1921, spent approximately twenty-four years practicing in the field of visual communication.

It is not entirely clear how Salvu Scerri got introduced to graphic arts. In his résumé he states to have studied drawing with prominent artist Edward Caruana Dingli, presumably at the Malta Government School of Art in Valletta. Scerri joined the British Admiralty Service in 1939, following the completion of his secondary education at St. Albert Central School in Valletta. His employment with the British services lasted until 1967 – over 28 years of service he worked as a Yard Boy and Labourer, served as a Corporal in Field Hygiene for his wartime military service, after which he moved to a clerical post with the Naval Armament Stores from 1945 onwards.

We have no clear evidence suggesting that Scerri trained or worked professionally as a graphic artist up until circa 1954, when he applied for a one-year distance learning course in Press Art at London Art College. Scerri’s son, Joseph, who is also a graphic designer, believes his father was encouraged to pursue commercial art by tutors at the Malta Government School of Art. At this time, training in the graphic arts was not offered locally – commercial art had not fully emerged as a recognised profession on the island, as yet.

When considering the colonial post-war context that was shaping Malta at that time, it’s no surprise that Scerri looked towards the British for his design education and main point of professional reference. This course suited Scerri perfectly, as it was a part-time skills-based course that allowed him to learn the basic practices used in contemporary British commercial art, while balancing his work and family life in Malta.

The London Art College had been founded recently, in 1931, by a collective of working artists and art editors whose aim was to create a practical alternative to the academic art school model. Leading the collective was A.W.Browne, a renowned editorial artist (press artist) of Fleet Street, then the home of the British newspaper industry.

The course consisted of 10 lessons covering lettering, figure drawing, pen and ink illustration, wash and half-tone drawing, colour painting, advert design, book jacket and cover design, catalogue illustration and fashion drawing, cartoon strip drawing, and mechanical and machine drawing.

Through the written correspondence between Scerri and Browne, one can admire an eager student – curious, patient and hard-working, and very keen to absorb as much knowledge within and beyond the course. In his questions and observations Scerri clearly showed he was thinking ahead about how to apply as well as introduce newly acquired skills and practices in the local commercial art scene. In fact, Scerri seemed to have been applying his skills before the end of the course – in a letter to Browne, from April 1955, he proudly mentions an artwork he had produced and submitted for the Malta Trade Fair poster competition, while also expressing his disappointment at the selection panel’s apparent inability to declare any winners that year, in order for the commission to be given to an established fine artist.

Following the completion of the Diploma in Press Art, Scerri appears to have gained the skills and confidence to set up a part-time freelance commercial art practice, at home, in Floriana. Between circa 1955 and 1968, he worked as a freelancer independently and for local advertising agencies the British Publicity Company (BPC) and Malta Publicity Services (MPS). BPC, an advertising agency founded by Joseph Brockdorff in 1958, largely employed British ex-servicemen with a background in commercial art to run its studio in its early days. According to Joseph Scerri, Joe Brockdorff had mentioned to him that Salvu Scerri could have been the first Maltese commercial artist to be employed by his company, and was considered to be a true graphic artist, when compared to other local contemporaries of his.

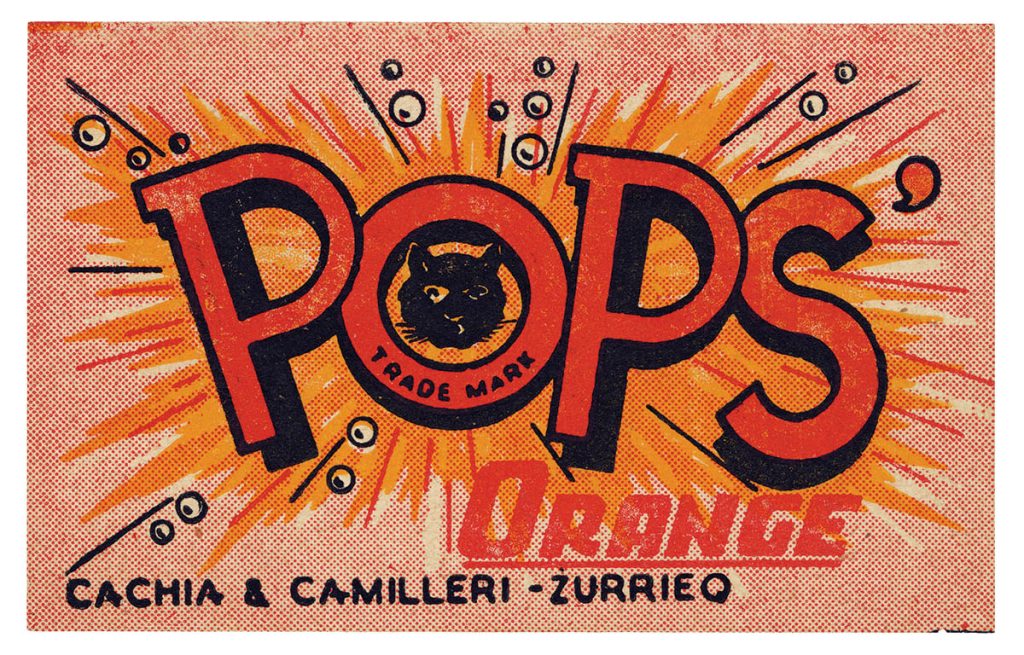

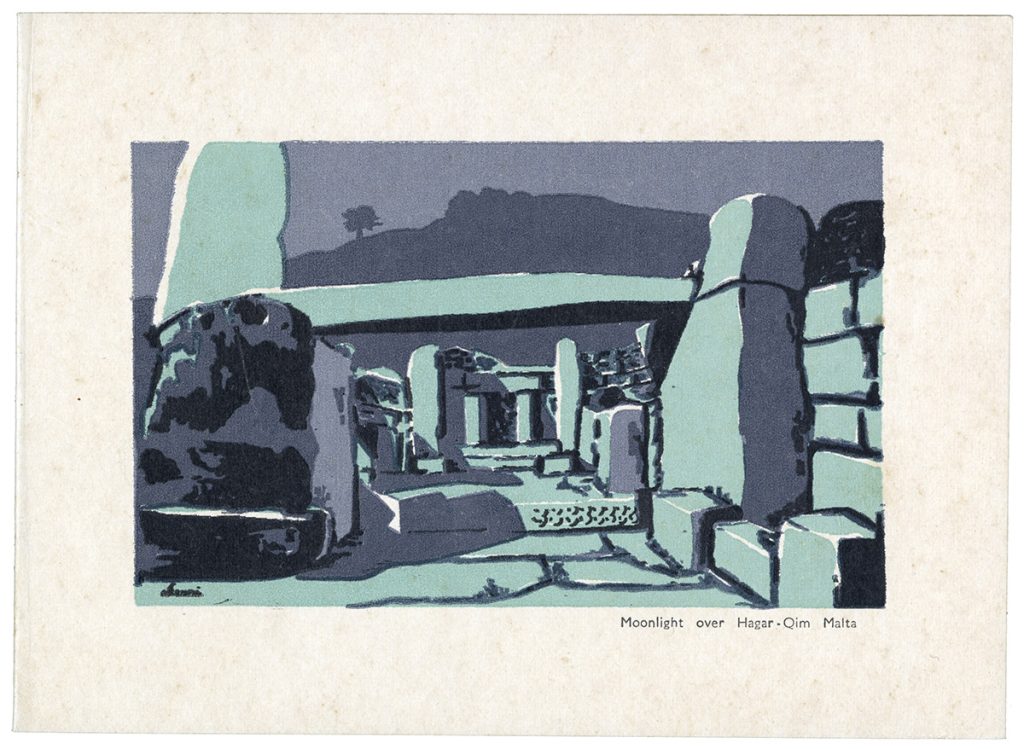

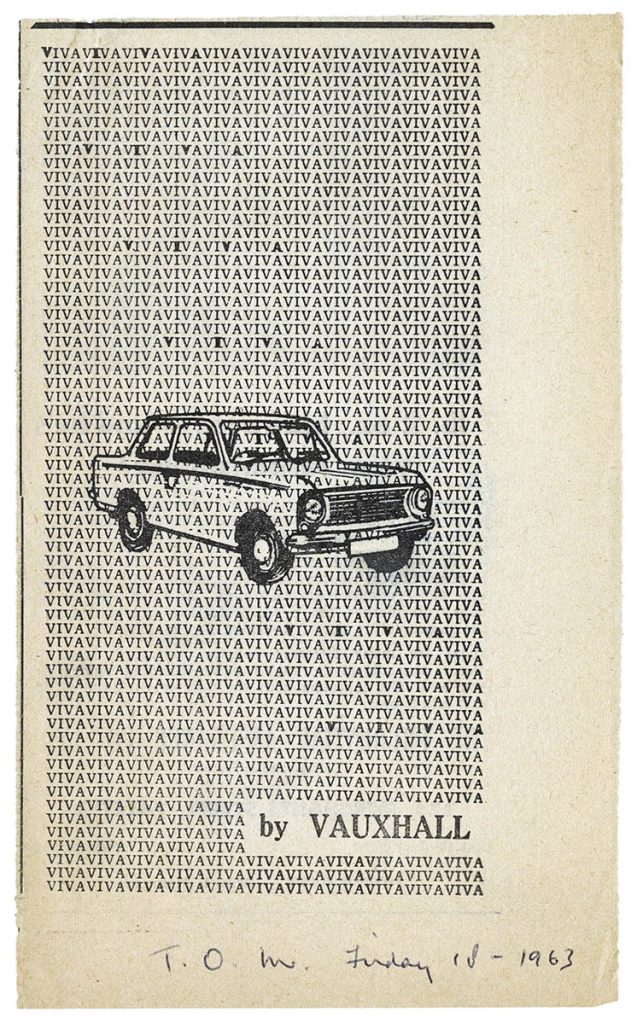

Scerri designed artwork for a wide range of outputs, including packaging and point of sale displays, press adverts, leaflets, brochures and posters. He worked with some of the best known local printers of the time – Bonavia Printers of Sliema, Valletta’s Clear Type Press, Union Press, Progress Press and Floriana’s Empire Press. Scerri used to recall an anecdote concerning the start of his long working relationship with Bonavia Printers, whose owner on their first meeting, apparently threw himself to the floor in awe of Scerri’s diligent work in artwork overlay registration! For pre-press work, Scerri regularly used British suppliers such as Hood & Co. of Middlesbrough – this mostly consisted of artwork block-making to be used on letterpress units.

Scerri’s approach and visualisation was clearly influenced by the distinctive style of mid-century modern graphic design – a modernist design movement that emerged between the mid-1940’s and mid-1950’s in America and Europe, visually defining the optimistic spirit of the post-war period. As a style it applied the rationality and simplicity of modernist design, with an added emphasis on eye appeal and playfulness. Scerri’s work shows varied application of this style, but doesn’t rule out the use of ornamentation.

A common tendency from this era was for commercial artists to merge the traditional boundaries between graphic design and illustration – Scerri’s graphic design work was often illustrative – graphically illustrative. He made regular use of media and tools such as cow gum, bow pens, indian ink, scraperboard, mechanical tints, air brush and Letraset.

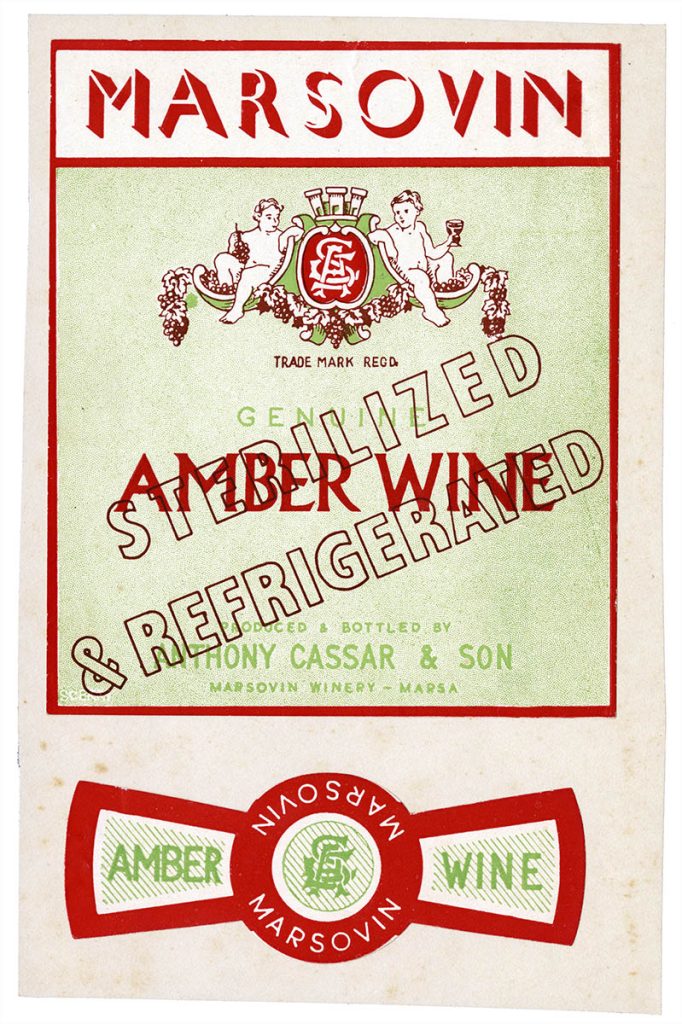

Scerri’s confidence was galvanized further in November 1956, when a set of labels he designed for local winemaker, Marsovin, were featured in the then prestigious Art & Industry – an independent journal of industrial design incorporating ‘commercial art’, published in London. As a budding designer, he must have felt a great sense of recognition and appreciation when seeing his artworks published alongside the work of established British contemporaries, Abram Games and Tom Eckersley.

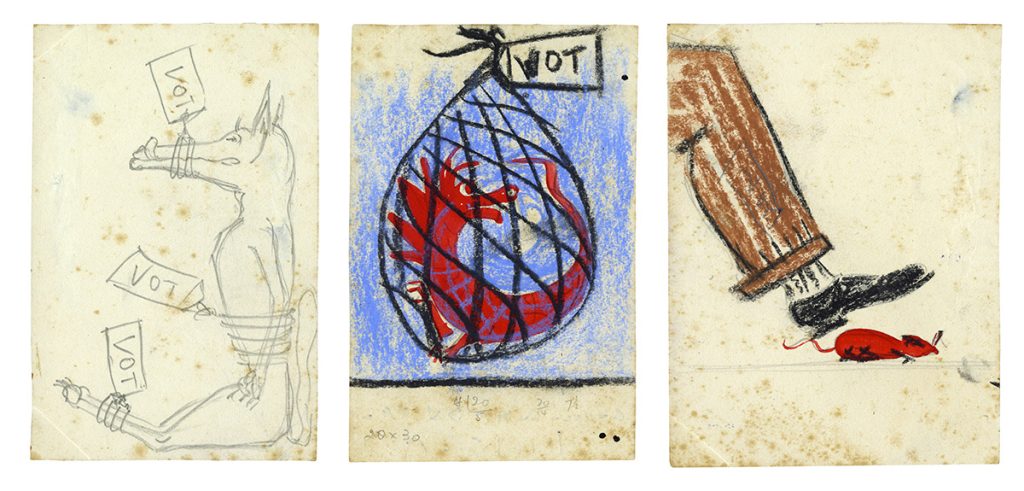

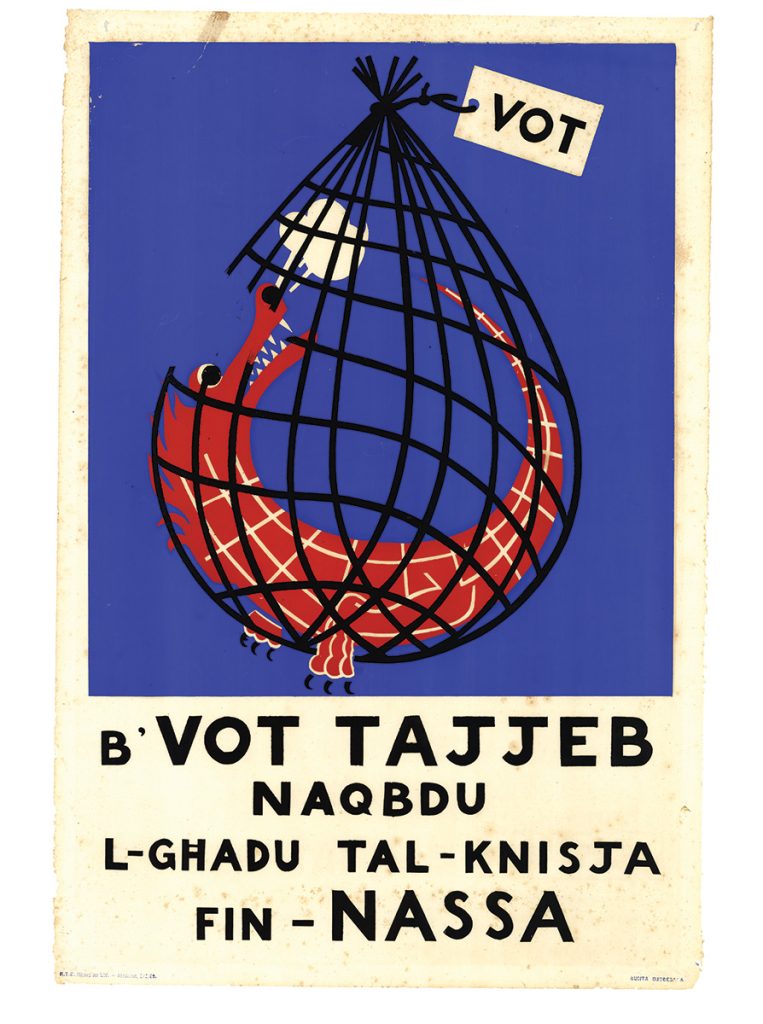

One of Scerri’s finest and most contentious set of works was produced in 1962, on a commission by the Diocesan Junta of Catholic organisations. The Junta, which had been set up in 1959, ran an extensive politico-religious campaign that staunchly supported five pro-catholic political parties which were running against the Malta Labour Party (MLP) in the General Election of 1962. This campaign emerged as a response to a long and bitter dispute between the Maltese Catholic Archdiocese and the MLP – the church was concerned about the dangers of Protestant influence in the form of civil marriage and divorce entering Malta, as part of the MLP’s plan to integrate the island with the United Kingdom.

Scerri designed a set of three bold and witty screen-printed posters, each communicating sharp messages that underlined the core arguments backing the Junta’s support for the archdiocese’s stand against the MLP. Artworks for stamps and flyers were also produced as part of this commission. The effective use of conceptual graphic symbolism and the reductive style employed by Scerri in this work, bears the trademark of an emerging graphic designer who had gained a good grasp of the functions and sensibilities of their profession. Nevertheless, this work was produced for a very controversial cause etched in Malta’s post-war socio-political history.

Following Malta’s independence from British colonial rule in 1964, Scerri’s full-time clerical post with the Admiralty started winding down gradually. In late 1968, after Scerri had left the British Services, Paul Laferla, who might have known of Scerri’s experience in packaging design, hired him as a full-time Chief Design Executive at Crown Cork Works in Hamrun – the company specialised in crown & can making, tin printing, process photography and plate-making. Besides heading the design department of the company, he was also responsible for budgeting, costing and stock control. This was the first time Scerri worked as a graphic designer in a full-time capacity. During this period, he was elected as an associate member of the Institute of Printing, London (1974), and as a lay member of the Society of Scribes & Illuminators, London (1978). The latter is linked to Scerri’s keen interest in calligraphy – a specialism he went on to practice on a freelance basis – from 1966 he was the official engrosser for graduation and ceremonial documents issued by the University of Malta and the Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller.

Throughout his full-time employment, Scerri appears to have kept his freelance practice going, from his family home studio, now located in Birkirkara. According to the details on the studio’s letterhead the practice was called Grafoteknik Art Studio and specialised in Graphic Art for Press Advertising, Technical & Industrial Design, Architectural Rendering, Illustration, Tinting & Retouching, Make Ready & Production, and Engrossing. His son, Joseph, who was introduced to graphic design as his apprentice at Crown Cork Works, also recalls his father running well-attended private lessons in graphic art at their house in Birkirkara.

Scerri’s career reached an end in January 1978, when he retired following a near fatal heart attack. He went on to live for another thirty-three years, during which he emigrated to Canada with his family in 1982, and returned to Malta in 1987, where he remained until 2011 – he passed away at the age of 90.

His legacy as a graphic artist lies not just in his creations but also in the community he helped build around graphic design.

Marco Scerri is a third-generation graphic designer, following in the footsteps of his father, Joe, and his grandfather, Salvu Scerri. His design practice is based in Glasgow and teaches at Edinburgh College of Art, University of Edinburgh.