Art Too!

Does the Maltese artist stand up to be counted?

“The revolution introduced me to art, and in turn art introduced me to the revolution”. Albert Einstein

Art has always played a fundamental role in revolutions, and artists have always been on the forefront of every major philosophical and sociological upheaval. Interestingly, when it comes to the plight for gender equality especially, but certainly not only on the local scene, artistic community and the art market have often been perpetrators rather than vehicles for change. Renaissance female painters had to pose as men, muses were treated like prostitutes, sketched, painted and sculpted by men for men to buy and enjoy and even today more than 80 per cent of work in commercial galleries are by male artists.

One could expect to forgive artists for having delusions of male superiority or plain old chauvinism. But contemporary society is even prepared to condone behaviour that is far worse than that.

Julian Andeweg, a 34-year-old Dutch artist graduated in 2012 at the Royal Academy of Art (KABK) in The Hague. In 2018, he was nominated for the Royal Prize for Painting and at the prize giving ceremony at the Royal Palace, he is introduced to the king of The Netherlands. The art groupies like him for being a typical bad boy artist, but big reputable wealthy commercial institutions like De Nederlandsche Bank, ABN Amro, the Leiden University Medical Center and the Bonnefantenmuseum own works by him. Not too bad for a dude in his early thirties.

Recently, the art world almost enjoyed hearing how four women had reported that they had been victims of Andeweg, accusing him of stalking, sexual assault, domestic violence, and rape to the police. And yet, the art magazines report, his career was hardly scathed.

We won’t even go into the world of theatre and film. Even on this little island, scandals abound. And the victims are expected to get on with it.

The art world, in forgiving, is complicit.

It is also complicit when it revels at works that attempt to highlight the abuse and shies away from those that portray the abused. Presumably because the first is deemed thrilling and intriguing, while the second sad and dark and the buyers desensitized and bored by the subject matter.

It is complicit when it chooses which plights to support, while ignoring those which it somehow collectively chooses not to.

It is complicit when it chooses to drop activists and keep rapists and mysogynysts on board. Because they are interesting, or cool, or have a story to tell than is more sensational than the story of those permanently scarred by them.

Seldom have I entered a classically decorated home in Malta that didn’t have a depiction of Suzanna and the elders. I always wonder whether the Maltese fascination with this painting is due to its almost pornographic nature, or else perhaps because it is some sort of badge – a symbol of their female ancestors’ allegiance to the modesty club. A sort of ‘behave and beware’ tactic, passed down from mother to daughter.

Is it possible that the visual rhetoric of Suzanna’s wannabe rapists, permanently hanging above the formal dining table, help to justify to persons who fantasize exercising sexual power over frail lasses that their behaviour is ‘normal’? Or to tell granddaughters that being ogled and undressed by men is just, you know, how things have always been!

It is almost as tough we are still in 1906, when Greta Weneger scandalised the Danes with her painting of a gender-neutral figure sometimes.

Museums too?

What should the museums do? Should they promote harbingers of suffering in the name of freedom of expression and leave it at that? Do they disclose the artist’s criminal record in the fancy bio at the start of the show and perhaps even base PR for the show around it? Do they disassociate themselves from the artist’s habit of sending his lovers to the ER? Do they hide their shameful collections in their basements, or sell it back to the artist or heirs? Or do they just pretend they don’t know anything about this little detail?

Where are the memorials? The permanent sculptures? We build a $700 million dollar memorial for 9/11, but have never seen a memorial for the 50,000 women a year killed by their husbands or intimate partners – 2,000 of which happen in the United States alone. Locally, public opinion, as witnessed by comments on social media, repeatedly exonerates the rapist or murderer and blames the victim. The fact that a person owns that sort of body is enough to make her guilty of seduction and entrapment. One reaps what nature sows, I suppose.

We need installations such as the one by Turkish artist Vahit Tuna, with 440 pairs of high heels, the number of women murdered by men in Turkey in 2018, symbolising the victims of domestic violence, in Istanbul. But mostly we need to acknowledge the artists who have been creating powerful and remarkable works that empower as much as they divulge and expose.

It starts with artists taking control of their own bodies. With stating, singing and depicting exactly what they think or want their body to do or be. They need to talk about whichever parts of their body they want. They need to tell the world that hiding it or refusing to talk about it does not mean that anyone who messes with it need not feel shame.

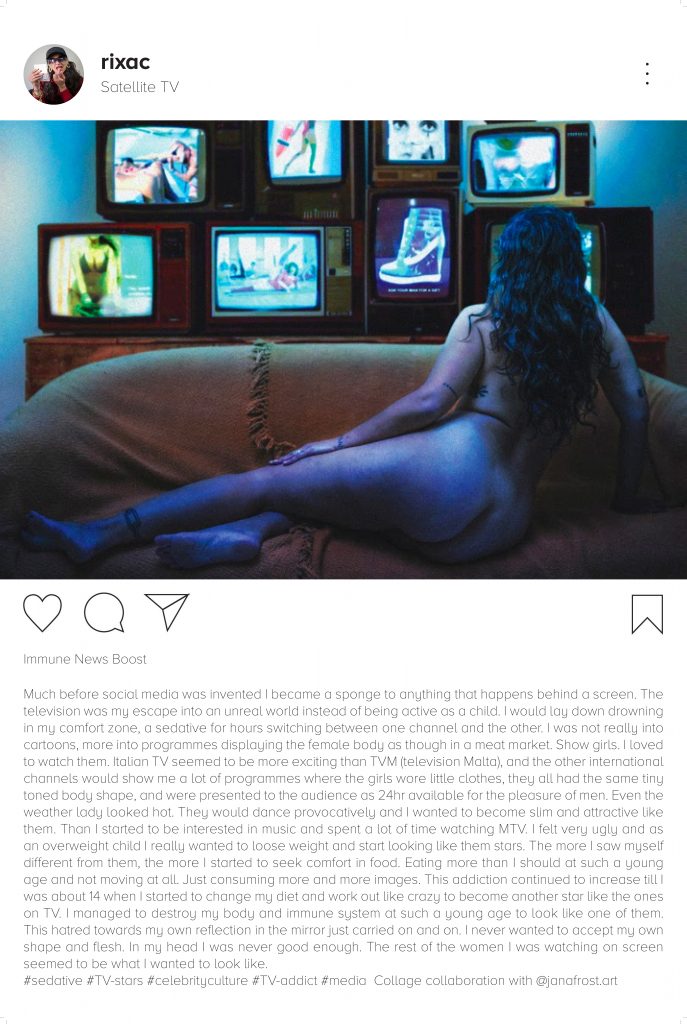

In Malta, social media platforms such as Instagram have given artists like Charlene Galea the ease of visibility without the red tape. At the same time, she wonders if the online world is making women ‘more seen and less heard’.

“I actually have a lot to say… because when my last work in the mill was about being a woman and the online female identity… where I have used my body openly even though I know how society can judge me as my work has mostly been photography. But basically, since I came to Malta after living away for so long… I knew that no one can stop me using my body freely after my freedom of my body has been taken away as a child.”

In the 1960s, performance art became a potent new medium for discussing powerful traumatic experiences such as rape. Yoko Ono, for instance, in her work Cut Piece (1964), sat on a stage and invited the audience to cut away her clothes.

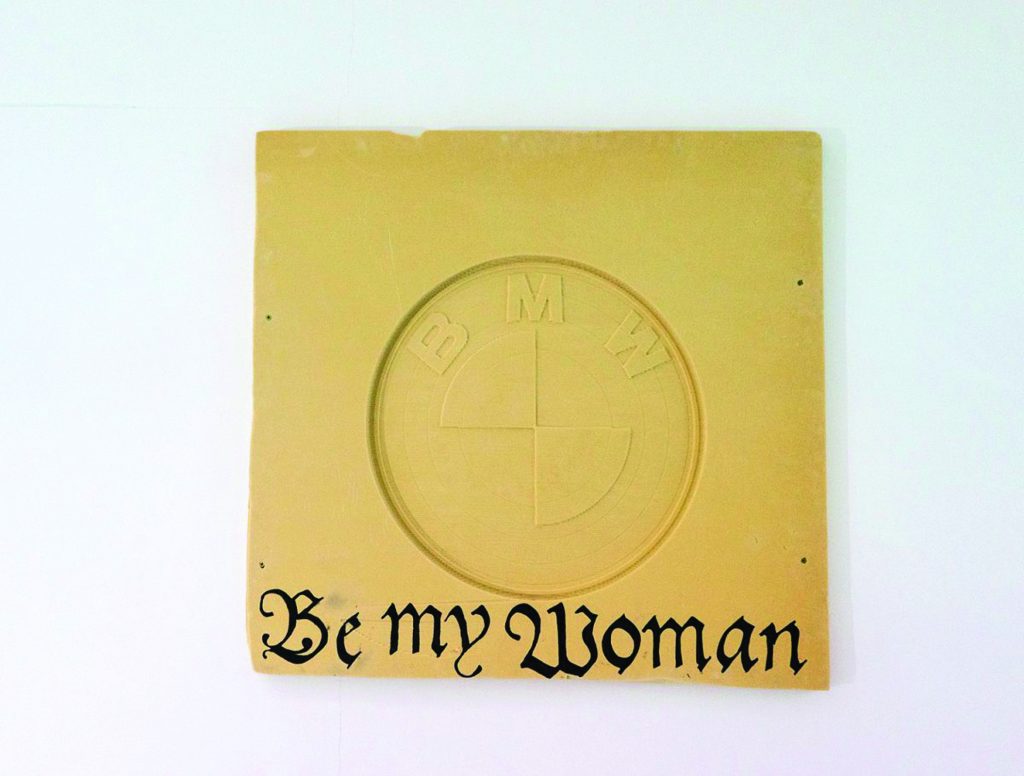

Images above are photographs of installations and a performance at Roxman Gatt’s first solo exhibition ‘Perfiction’, where the complexities of contemporary human experience were articulated through an installation of sculpture, film, painting, poetry and performance. The exhibition was centred around the image of the car, a symbol of male, macho, consumerist, capitalist culture.

London-based Maltese artist, Roxman Gatt, often explores sexuality and unashamedly portrays very honest aspects around the subject. Roxman Gatt recently worked on a project that reclaims derogatory words used to supposedly insult women, and is careful with words calling the work My Womxn is a God My God is a Womxn, fully aware that ‘Womxn’ has become a problematic term – especially if used by cis women [and transphobic people] or out of a specific context as it is hurtful to some trans people.

“However, I, someone who is non-binary, was using it in a completely other way; a way to be more inclusive of non-binary and trans people.”

The work comprises six tunes and visuals to go alongside them, as well as a choreography performed with five other people, and of a set of three large canvas paintings a sculpture and wearable sculpture plus a couple of other props.

The broomstick sculpture, for instance, was inspired by the iconic witches’ broom, which is connected to a fear of female sexuality – the idea that women were perverting domestic tools of womanhood for their own pleasure. The performance and tune Slut, is inspired by the words of Samirah Raheen’s response to a right-wing pastor calling Gatt a slut and slamming her choice of clothes.

I loved the honest self-portraits by Martina Mifsud, in her recent show Point of You, curated by Andrew Borg Wirth. In her contemporary selfies, painted in oils in large format, Martina becomes both muse and artist. Breaking right through that stereotype on canvases that are unashamedly powerful.

Malta-based artist, Charlie Cauchi, researched the borderline fantastical Maltese run brothels in soho – with her research being immortalised in her exhibition, Sheherazade, held at Valletta Contemporary at the end of 2019. “Wash your hands before you dirty your fingers”, said one of the teeth grinding inducing slogans on a light box piece.

Throughout the installation, she reminded us that women, their bodies, were expendable commodities – used, sold, resold and ultimately discarded at the whims of men who cashed in on their creative ideas for their possessions’ many uses.

Kevin Attard, a filigree artist, launched a set of pendants depicting a few of the infinite variations the vagina can have, in a bid to use this rather traditional jewellery genre in a contemporary setting. The images are set to become symbols of the very belated attempts at breaking taboos surrounding female sexuality and sexual reproductive health. In fact, proceeds from the sale of the ‘pussy pendants’ are in aid of the women’s rights foundation, and the Women4Women foundation.

I feel art drives and in return is driven by shifts and radical changes in society, yet I just don’t see it doing anything for emancipation. It’s too little, too slow, and way too late. Especially locally. Art sales are stacked towards the male artist. The narrative is still that of the powerful artist helping his muse open up and explore her sexuality. The owner of the body of the figure lives in the shadows. No one knows her name. Even though her intimate body parts are painted in detail while the male model reserves the right of appearing more subtle, less vulnerable. Or at least those are the images that are deemed sellable.

Violence is still venerated in the arts, and while we build memorials for every political martyr, 50,000 women a year are killed by husbands and intimate partners and zilch. Some people tell me that I manage to find a bitter gender angle to everything. Well, that’s because there is one. Always. And perhaps supporting artists who shine light on it might one day blur that angle into obtuse oblivion. And if buying a silver pussy pendant and wearing it around your neck helps spread the word, then why not!