Uncovering Narratives

Ibrahim Mahama | Gozo | Until 31 May | maltabiennale.art 2024

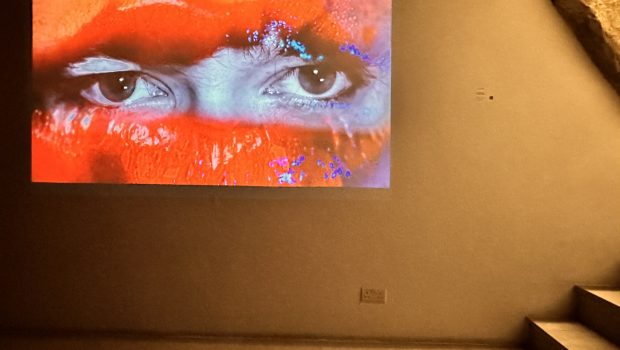

As part of the “Decolonising Malta” section of the first maltabiennale.art, Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama put the prehistoric stones of the Ġgantija Archaeological Park in dialogue with parts of the installation “Garden of Scars”, referencing stones with a very different but equally mystical history.

Originally commissioned by the Oude Kerk, a former church now centre for contemporary art in the centre of Amsterdam, Garden of Scars is the result of Ibrahim Mahama’s process of “time traveling”, as he calls it, “rerouting the residues of colonial and postcolonial utopias to create new opportunities”. Hundreds of concrete sculptures resulting from this process are currently populating the Gozitan archaeological site in a discreet yet compelling manner, urging visitors to make an unexpected imaginative effort grounded in African and European colonial history.

“Materials always hold the embodiment of souls, which allows us to have these extended dialogues.”

Ibrahim Mahama

The sculptures were produced from silicon moulds of the tombstones of thousands of merchants, captains and mayors buried in the Oude Kerk, people who contributed to exploitative colonial dynamics and who may have greatly benefited from them. Traces of this history of inequitable exchanges remain evident in Ghanaian built heritage too, especially on the coastline, where forts and castles were built by European colonisers to safeguard their goods and slaves, before shipping them across the Atlantic. “Stones would be transported on ships from The Netherlands and other European countries in order to build these forts and castles” Ibrahim Mahama explains while describing the process of production, which reversed the direction of the movement of materials. The silicon moulds of the tombstones travelled from Amsterdam to Tamale, in Ghana, and then back to Amsterdam, in the shape of thousands of sculptures. At Red Clay studio in Tamale, the team led by Ibrahim Mahama used the moulds to generate artefacts made of a mix of Ghanaian soil, aggregates, dust and fragments from abandoned buildings, together with objects collected from different locations. Embedded in the concrete are lamps, pieces of wood and furniture from the British colonial time which are reminiscent of that part of Ghanaian colonial history too, when railways were being built for the transportation of goods and timber from the forests of inner parts of Ghana to the harbours on the coast. Each material carries a piece of colonial history, in relation to specific places, people and times. “It’s a history of materials, the relationship between the materials and the space is very important to me” Ibrahim Mahama says, illustrating how he focused on the memory of the spaces he interacted with, and how he produced a new layer of memory as a result.

Each material carries a piece of colonial history, in relation to specific places, people and times.

After being produced in Ghana, the series of concrete sculptures referencing the tombstones of men who were most probably involved in the shipping of those stones used to build forts and castles, were shown at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, in 2023. Some of them are now reconfigured in Gigantija, in dialogue with stones that represent time before recorded history, predating Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. In doing so, they encourage the uncovering of narratives that are often overlooked in favour of the dominant ones, and they build new connections between distant places and times, evoking the past while making an impact in the present. In line with the curatorial intention to “position Malta at the centre of a Mediterranean that expands to the east and west, suggesting new methodologies of coexistence and relationships”, Garden of Scars prompts an extraordinary re-imagination of habitual perspectives. The sculptures, which lie like actual tombstones in a cemetery, evoke the spiritual character of the megalithic temples while engaging dialectically with them, re-activating the spirit of the place. “Materials always hold the embodiment of souls, which allows us to have these extended dialogues” Ibrahim Mahama concludes, reminding us of the sheer amount of responsibility that we carry in relation to global dynamics of migration, movement, trade, but also of reuse of materials and rehabilitation of heritage.