The Colour of Memory

Walking into one of the Tate Modern’s galleries on a decidedly grey London morning, I was caught in my tracks, unprepared for what lay in store.

Before me was a scene of pure Dionysian serenity. The dreary tone of that January day, that otherwise lifeless room, was suddenly offset by two sunlit interiors. In them were two nudes, women whose lithe forms were described, almost crudely, in a cadence of the most exquisite pinks, reds, ambers, honey and green, and I was faced with a dance of light, of heaven-sent colour.

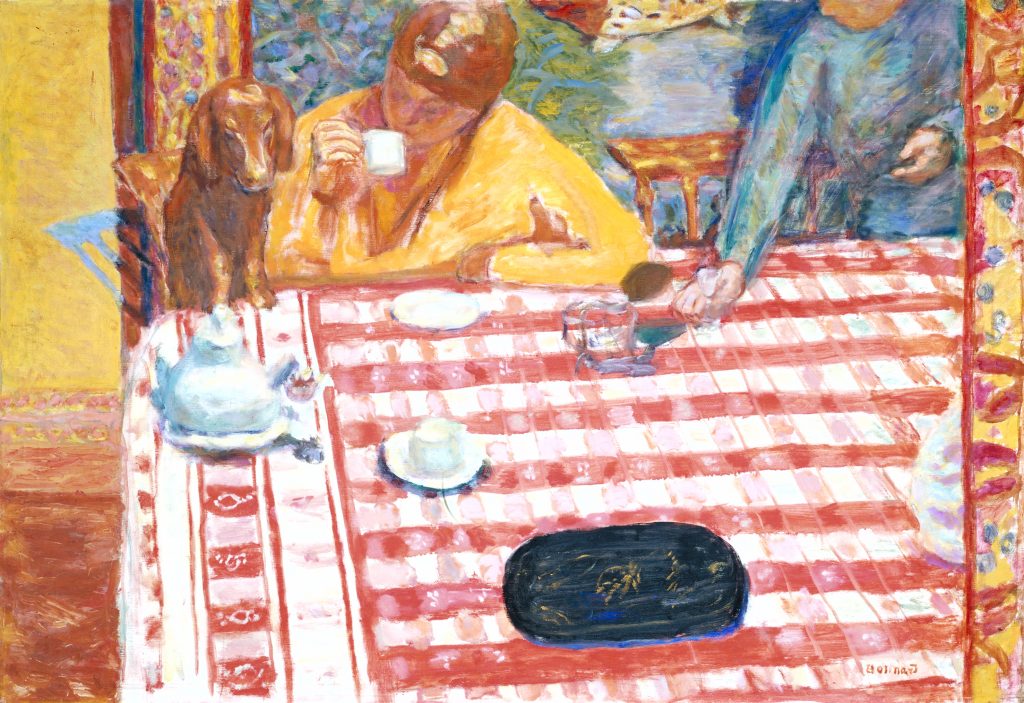

Those women glowed with the warm flame of life, of humanity, of sexuality, of a tame place to call home and the wild and fearsome spirit of the Mediterranean landscape all at the same time. Forget the devil; it was salvation that I found in those details: the clean crockery awaiting the midday meal, an empty chair, the tidy room, the perennial dachshund nuzzling its head on the chequered tablecloth in close anticipation, the glimpse of the brilliant blue sea outside. And suddenly, out of this mundaneness, this crystallised moment of expectation never to be fulfilled, all of existence seemed to have finally found its purpose.

As this comprehensive retrospective demonstrates, Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) is the kind of painter who makes you consider such fleeting moments, and to do so, he demands your attention. A slow worker, often obsessively returning to work on the same canvas over a period of many years, he invades your field of vision with an eclectic array of subjects, taking your very eyes hostage, insisting you become a slow looker in turn. Studying another small nude, this time with her back turned to the viewer, her figure enigmatically concealed by a doorway, a frame within a frame, I could feel the heat of the warm sun as it hit her back, illuminating the gentle swell of her hips with all the warmth of an evening sunset. It was a pure summer’s evening encapsulated in pigment and, looking at it, as with Proust and his Madeline, I was transported straight back, back to those long childhood days lounging on the rocks by the murmuring sea as the sun inched below the horizon.

It is always a delight to discover a painting that can have such a magical hold over you, and I use the word ‘magic’ here without embarrassment or hesitation. For what Bonnard pulls off time and again is nothing short of a magic trick, except here there is often real enchantment at play, not just smoke and mirrors. Working from memory, Bonnard immortalises hazy recollections in paint, transcribing them into beautifully amorphous visions where everyday objects become both iconised and simultaneously intertwined within a much wider composition.

In Bonnard, the subject of the picture is rarely any one particular ‘thing’, the edges of the canvas are always full of potential and activity, fragments of cropped figures like unwanted intruders in a family photograph. This could be the result of Bonnard’s working method – consistently revisiting unstretched canvases that hung on his studio wall, working and reworking them right to the edge – or it may be the result a more thought-out pictorial strategy, as attested by the hundreds of carefully considered and annotated compositional sketches that abound in the exhibition. In any case, the resulting sensation is that the scenes depicted exist outside the confine of the canvas and that life – messy and uncontrolled – continues to exist beyond the parameters of the frame.

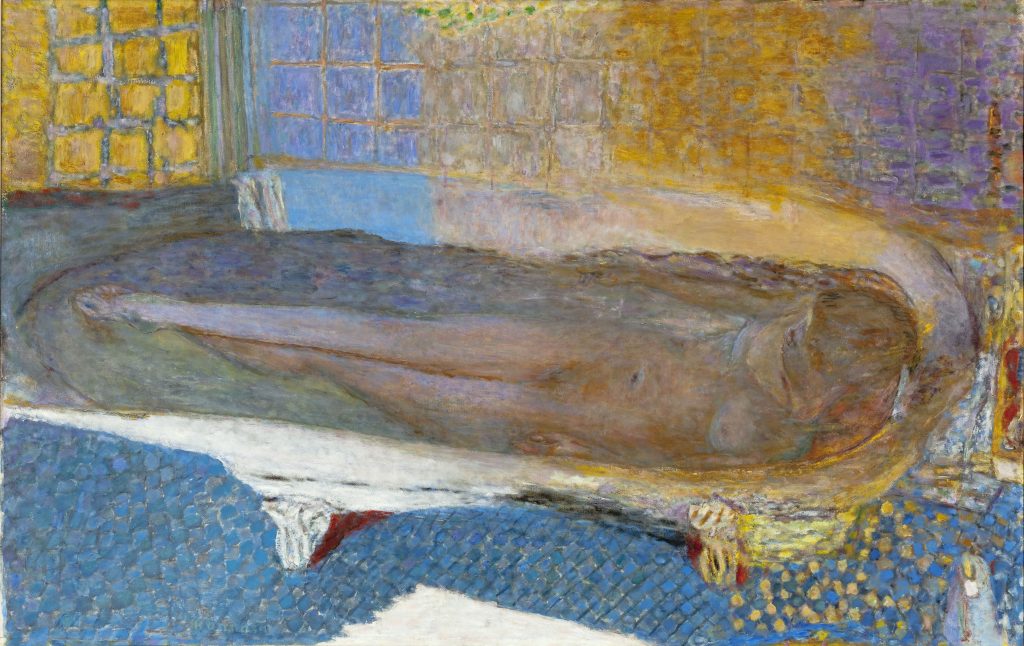

What Bonnard does, with great conviction, is make us reconsider the intrinsic value of the ‘things’ that make up the word around us – be they a jug, a cat, a tree or a bath – so that all of a sudden, they are everything and nothing all at once. In Bonnard’s hermetically sealed-off world, a bath might be just a bath, but it also seems imbued with immense symbolic value, as a source of life, a sustaining vessel, a transitory space, a site of transformation. It may also lend itself to a more psychologically-charged reading, a refuge for his wife Marthe, by all accounts a somewhat troubled and reclusive figure, often and famously depicted submerged in the bath, both purifying and distancing herself from the world outside those ever-present doors, those somewhat oppressively-patterned walls. Sometimes all the decoration, the rhythmically composed grids and lattices of vibrant hues, start to resemble a gilded cage, a prettily-tiled prison of either Marthe’s making, or of Bonnard’s own construction.

In another painting, Bonnard places his recent fiancée alongside his then-lover (Marthe) in an image of uneasy Arcadian placidity. Knowing that his bride-to-be would go on to kill herself when Bonnard called off the engagement to take up with Marthe, and that the existence of each woman was kept secret from the other in reality, lends this painting an eerie, haunted quality in spite of its sun-dappled surface. Indeed, the guilt that this event caused Bonnard apparently drove him to paint a series of much darker paintings than normal which may also have served as the artist’s commentary of sorts on two World Wars which are otherwise conspicuous only by their total absence, and it seems remiss that this period of the artist’s career is not expounded on further at the Tate.

Bonnard himself could be artistically uneven, too. Much ink has been spilt in outlining his skill (or lack thereof) in drawing at the technically proficient level that was advanced in the academic circles of the time, but I would protest this point, citing the aforementioned notebook sketches as evidence of a keen and refined sense of draughtsmanship. The wealth of intimate photographs taken by Bonnard and Marthe reveal another fascinatingly modern sense of experimentation with medium and reproduction, serving as direct sources for his painted scenes after being altered and rearranged.

This aspect of Bonnard’s practice, which has only recently been given any serious attention by academics, is all the more engaging to a contemporary audience as it so directly pertains to the very current discourse about the relationship between painting and photography (one need only think of the much more recent painterly translation of photographs in the work of artists such as Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans, for example). In my opinion, it also places Bonnard in a much more direct conversation with some of his French Impressionist predecessors (Mary Cassatt, Edouard Manet) as well as some of his other contemporaries further abroad such as the British artist Walter Sickert, who portrayed scenes of domestic mendacity while working extensively from press and personal photographs and with whom Bonnard’s work has been surprisingly unaligned.

Unlike a more figuratively astute artist such as Sickert, however, Bonnard’s somewhat lackadaisical approach to human anatomy is another aspect of his limitation as an academic draughtsman that can, on occasion, become somewhat distracting, especially as you begin to try and comprehend the mechanics of his arms and legs which often suffer from the same sausage-meat syndrome that affect many of his predecessor Turner’s similarly disjointed figures. A more critical curatorial eye could have been applied to this end during the selection process, especially as the show feels somewhat overstuffed as it is.

Ultimately, however, these are minor quibbles, as even Bonnard’s minor works leave us with much to admire. And when he is good, he is so very, very good. Some of his paintings, such as his lush gardens, enigmatic bathroom scenes and receding sea-backed landscapes are, once seen, unforgettable, where all else coalesces into a divine whole, rendering anatomy and perspective into irrelevant foibles. In Bonnard’s best work, to paraphrase John Fowles, he anoints even the most trivial of moments with an unexpected and stimulating reverence, so that the moment, and all such moments, can never be entirely trivial again.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory is on show at the Tate Modern until 6 May 2019.