Ruinous Beauty

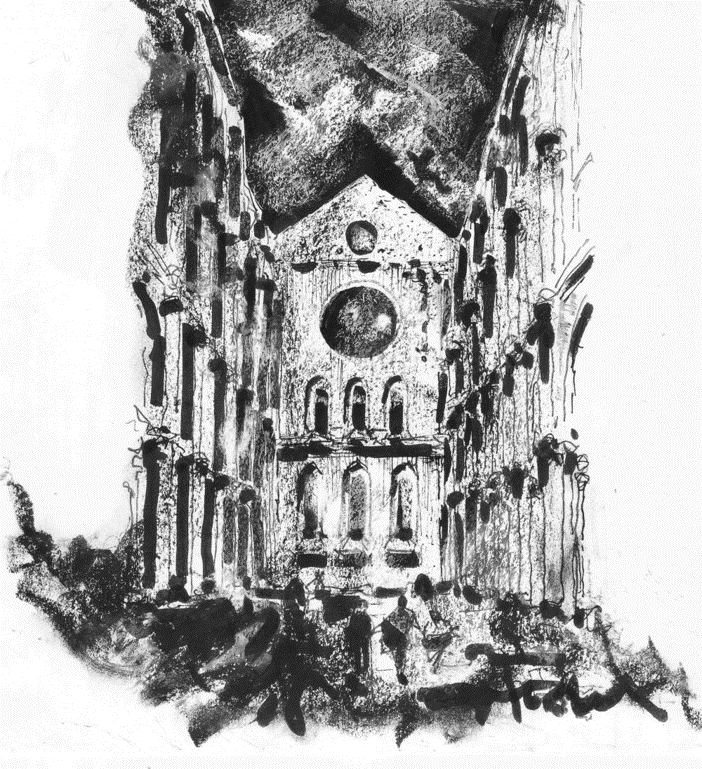

The mystical, mythical beauty of the thirteenth century San Galgano Abbey in Tuscany. By Richard England

The ruins of the abbey of San Galgano, a thirteenth-century Cistercian monastery, are located in the province of Siena in Tuscany, Italy. Today the abbey stands roofless – a magnificent skeletal carcass with its vertical walls and open windows focusing on the imposing end-apse wall as a visual climax. The construction of the abbey, which was started in the thirteenth century on the original site of an earlier hermitage, persisted for over six decades. The abbey flourished in its early stages and was then partially destroyed in the fourteenth century, with much of its building material looted for reuse in new structures. Today, the gutted ruins of Tuscany’s first church stand proud in the lush plains of the Val de Merse.

Adjacent to the ruins of the abbey lies the hermitage of Mount Siepi, a chapel built shortly after San Galgano’s death and where the sword of the saint still stands fused into the rock into which he had embedded it. San Galgano was a licentious bellicose knight who, after a visionary visit by St Michael, was convinced to give up his wanton and belligerent lifestyle, repent, and become a hermit. While riding, he was led by his horse to a particular site and – taking this to be a heavenly indication – planted his sword, in lieu of an absent crucifix, in the ground. As the sword fused into the rock, the knight understood that this was the divinely prompted location for the building of a church. The tale is not dissimilar to the Arthurian Excalibur legend of the same period. Today the ruins of the abbey provide a haunting spectral image, which must feature as one of the most mystical sites I have ever visited.

The building – modelled on a Cistercian architectural typology – provides, in its ruined state, a soul-enhancing, atmospheric experience with its gaunt, ashen shell structure creating an overriding sense of spirituality and mystical silence; a shelled armature clothed in ghost-like quiescence. Little wonder that the edifice inspired film maker Andrei Tarovsky to use the ruins for his 1983 masterpiece, Nostalgia. It seemed to me, on my visit, that the abbey’s haunting eerie open-to-the-sky spectre, with nebulous dancing clouds as its ceiling, was straining to tell its long-lost tales. The poetics of ruins move us deeply, perhaps because they remind us of our own transience. It is because of our fascination with mortality and death that our reaction to ruins is often crowned with a deep sense of nostalgia and loss. Ruins are read as remnant fragments shored against the consuming passage of time. It is also a truism that each one of us tends to build up and complete ruins according to our own imagination; the remnant real and imaginary blending into a present-day entity. A fragmentary poem found in the Exeter cathedral chapter library extols ruins – ‘wondrous is this wall-stead wasted by fate’. Rose Macaulay in her book The Pleasure of Ruins refers to our ‘ruin appetite’. Certainly, there is no doubt that the ghosts of buildings, hovering between survival and destruction, will ever continue to haunt us. These shipwrecks of time remind us of our own futility and transience, which is why we find them so poignant. The fatal embrace of decay and destructive time petrifies the surviving carcass of what once might well have been the sturdiest of buildings.

Buildings can in fact appear more beautiful as ruins than in their completed, original, intact state. The abbey of San Galgano is the perfect example to verify this.