Playing Cindy

More than ever, her work reminds us of the way popular culture, and its coded ideological conventions, informs our own everyday construction of reality.

Arriving at the National Portrait Gallery at the end of June, the first UK career retrospective of American artist Cindy Sherman will explore four decades of her work, from the seminal Untitled Film Stills series (1977-80) to the present day. Since she emerged in the late seventies, alongside like-minded artists like Robert Longo, Sarah Charlesworth, Barbara Kruger and Sherrie Levine (a group subsequently known as The Picture Generation), Sherman has consistently questioned issues of representation and gender in mass media while assuming the role of artist and model in her own work.

Along with her contemporaries, Sherman re-appropriates popular culture as a means of critical parody, adopting the mise-en-scène of glossy magazines, advertising and cheap B-movies to investigate the blurred separation between artifice and reality. In an age of selfies, where self-representation is commonplace, Sherman’s works are both prescient and influential in how they straddle binaries of subject and object, subtlety and brutality, candour and voyeurism, attraction and repulsion. More than ever, her work reminds us of the way popular culture, and its coded ideological conventions, informs our own everyday construction of reality.

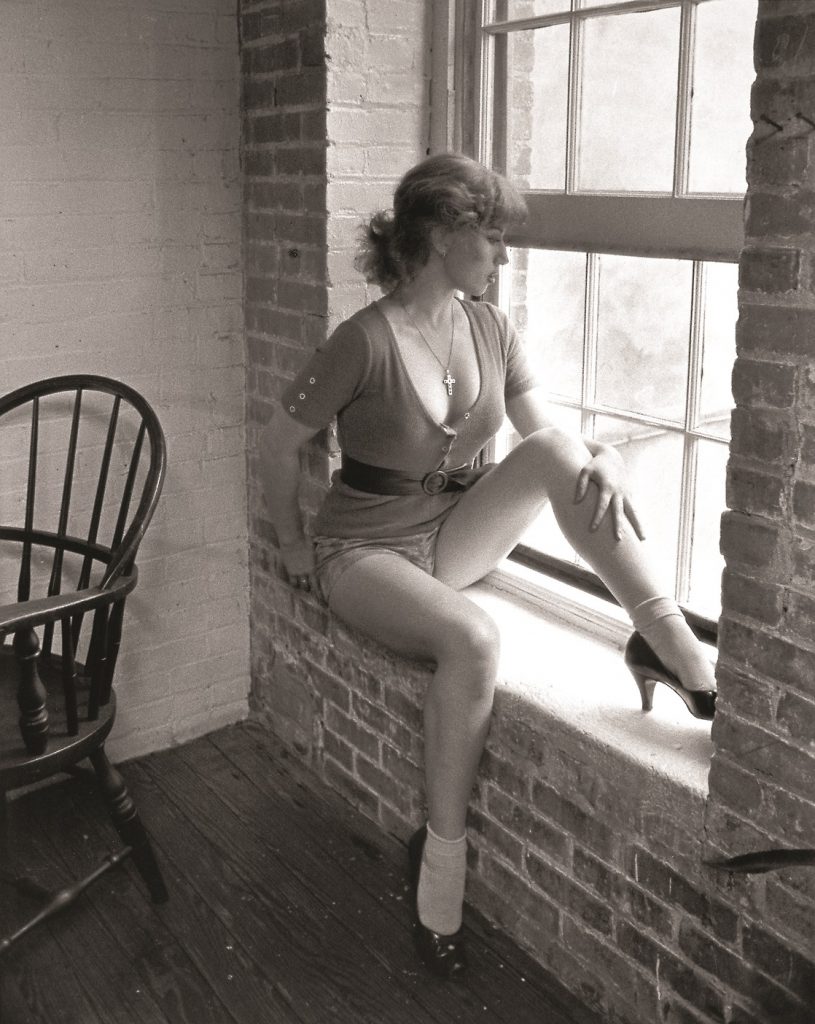

Shown in the UK for the first time, Untitled Film Stills comprises 70 monochrome images of the artist in various disguises, initially shot in her New York apartment and then outside in urban locations with the assistance of Longo. These modestly sized photographs, which launched Sherman’s career, see her shape-shift into a series of stereotypical female character tropes as represented in both American and European cinema throughout the fifties and sixties. From librarian and school girl, to femme fatale, hillbilly and vixen, the images replicate the lighting, angle and poise of conventional film stills while implicating a familiar, if unspoken, narrative.

Always alone, Sherman’s heroines display an undercurrent of anxiety, their faces, caught between melancholy and silent contemplation, suggest internal anguish. These generic icons both parody the dominant depiction of the female and reflect a search for identity while most importantly, suggesting the idea of femininity as a masquerade. In doing so, the series acts as a critique of Western art and the aesthetic vocabulary of popular culture as satisfying a voyeuristic male gaze. The guises offer little insight into the character of these women, they are presented as fetishised, passive and ever-available objects.

Elsewhere, the exhibition includes Sherman’s 1981 commission for Art Forum, Centerfold, a pastiche restaging of men’s magazine pin-ups with the artist adopting the role of sultry and vulnerable seductresses. Though they were ultimately rejected by the magazine’s editors for their perceived ambivalence (one photograph of a dishevelled blonde woman in bed with the sheets pulled under her chin was interpreted as suggestive of rape), the power of these coloured works is their implicit ability to reflect the viewers’ own desires. Their connotative nature plays on the viewers’ acquired receptiveness to the visual codes of mass produced imagery.

In projecting our own narrative beyond the single frame snapshot, the image reveals the way invisible structures of representation, perpetuated by films and consumerist advertising, have come to shape our everyday reality. Like Untitled Film Stills, Centrefold frames femininity through a voyeuristic lens, these are women to be looked at, though their sexuality is somehow muted, coupled with an innocence that suggests awkward teen insecurity. Where they differ, the soft, interior colours and repeated horizontal format of Centrefold fail to accentuate the vulnerability of Film Stills, in which Sherman is presented at odds with the environment, susceptible to its dangers.

Also included in the show are Sherman’s Sex Pictures, a series created in response to America’s Culture War of the 1990s, in which liberal progressives and conservative traditionalists fought for the moral identity of America. Amidst fierce ideological conflict on issues ranging from gun control to abortion, LGBT rights and state censorship, Sherman’s 1992 series came to the defence of artists like Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano who were identified by conservatives as key instigators in America’s moral collapse. Unlike the majority of her oeuvre, Sherman takes herself out of frame for Sex Pictures, instead using dismembered doll parts, masks and prosthetic genitalia to stage dark scenes suggestive of mutilation and sexual exploitation.

In their twisted and contorted corporeal states, the images are redolent of German Surrealist Hans Bellmer’s life-sized pubescent dolls. Bellmer’s work subverted the idea of a child’s toy while suggesting a corruption of innocence. Sherman’s images on the other hand serve as a critique of hard-core pornography and an ever-growing cultural obsession with sex and violence. Like Bellmer, Sherman’s dolls waver between seduction and repulsion, sadistic and fetishistic, accentuating features most conducive to the male gaze. In one, the prone figure of a naked doll strikes a familiar pin-up pose with hands clasped behind its head. The doll bears the face of an old woman and its legless hips reveal a gaping vagina while its torso is reduced to breasts and a swollen stomach. The image succeeds in highlighting both a social discomfort with overt sexuality and the objectifying nature of pornography, thereby extending as a protest against liberal ‘political correctness’ and conservative censorship. More generally, the images continue Sherman’s investigation into the representation of femininity in mass media, proving, as she had done so already, the ease with which we conflate fantasy and reality.

Cindy Sherman is on at the National Portrait Gallery, London 27 June – 15 September 2019.