In the Beginning There was Silence

A conversation with artist John Paul Azzopardi

“Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.”

Arthur Schopenhauer

It is easy to get carried away with words, and it is simpler still to get carried away by our own thoughts. But, as Khalil Gibran would put it, in speaking, much of our thought – and also our art – is murdered. Such was the nature of my conversation with Gozo-based artist John Paul Azzopardi, one fine afternoon in some corner of a coffeeshop. Questions bounced between us, eliciting reactions and comments on aesthetics, time, solitude, desire and freedom, wealth, integrity, the sacred and the metaphysical, existence. I wanted to pick at his brain, but my hand could not keep up with the pace and spontaneity of our exchange. Later on, faced with the daunting whiteness of a blank document, I grappled with the essence of what we had talked about. I slowed down those racing thoughts, selected and meditated on them, and wondered whether this was precisely John Paul’s own approach before creating one of his sculptures; to fish in silence, in a flowing stream of consciousness.

www.lilyagiusgallery.com

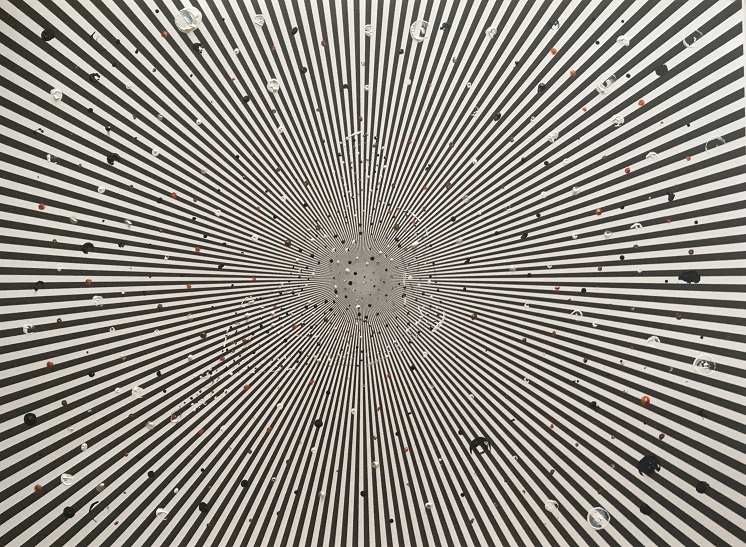

The contemporary debate on art, on what constitutes an artwork and even on its practice, has not really shaken off the clutches of the classical considerations on form. Even though John Paul’s works (most are familiar with his meticulously constructed bone sculptures) nudge any conversation about them to go in that direction – towards the realm of form, method and technique – he is not particularly keen on discussing such topics. “It’s more about going into the space of the form, rather than the form itself that interests me. It’s a way of going into silence, of experiencing pure presence”. The basis of his thinking, and also of his method, is greatly indebted to Eastern schools of thought and worldviews, particularly that of Hindu philosophy, which advises on the paths of spiritual realisation. Creativity – creation – also belongs to this path. The experience of pure presence could be likened to that liberating moment while staring at the sea, that moment when nothing else matters; thoughts are free and detached from you and your own limited concerns on things that were or that have not yet been. “The sea,” John Paul tells me, “is where I want to go with my work”.

www.lilyagiusgallery.com

But to go to the sea, metaphorically speaking of course, is no mean feat. It takes time and patience; it is a risk. To go out to sea might also mean that the people on the shore will lose sight of you. For them to be misunderstood or misrepresented would not come as a surprise. The works need space, for they were created in space.

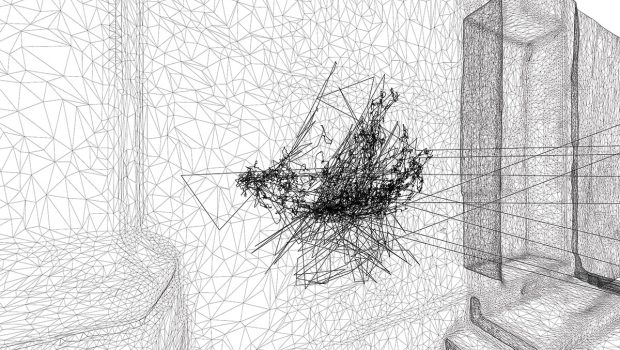

When viewed closely, the bone sculptures are seemingly chaotic and dense, but naturally, order emerges from chaos. For the ancient Greeks, ‘Kaos’ emerged at the dawn of creation from a gaping void – from emptiness and darkness. It is perhaps no mere coincedence that the closely related word kairos, also in Greek, refers to that opportune time, that absolute time for something to happen. It is as if to say that creation could only occur at the moment of chaos.

In other words, something positive could emerge from a shadow. “Chaos can trigger things in your mind that can also be cathartic,” reflects John Paul; “through shock, one can heal”. The bone sculptures are demanding and require, from the artist, a great sense of stillness, of certainty and concentration, but also of vulnerability. It was a means for John Paul to come in touch with his inner turmoil, to soften it – like the bones themselves before being placed within the complex matrix – and to understand the roots of what caused it. The turmoil is there, but so is the stillness, and the fragility of this dichotomy may be quite easily perceived when taking in the sculpture as a whole, irrespective of what it represents. Thus, the sculpture is less about decay or death than it is about that positive experience of space and growth in silence. And if it should be about death, decay or loss, then it is more about the ‘death of the ego’ than it is about any cultural or material death.

I was keen to understand why John Paul feel his bone sculptures do not work with a contemporary audience (I feel would dispute this, since many find his work fascinating). Death, I thought, is something we all come face-to-face with at some point – we fear it and the uncertainty it brings along, and yet it enthralls us. Tragic car accidents are disturbing, yet most of us slow down and slide a quick glance as we pass by. Likewise, ruins are beautiful when their destruction comes about, not senselessly – like the vile terrorist destruction of unique heritage sites and museums – but in the “realisation of a tendency inherent in the deepest layer of existence of the destroyed,” as German sociologist Georg Simmel would argue. Ruins, like relics, are attractive because they embody memory, life and death all at once – they embody the past, the present and the future (or the possible) in a harmonious contradiction of sorts. “Only, my sculptures are not about death. They do not work in a society that grapples with the challenge to stay with one object. They do not work in a context where art is consumed”. Isn’t that enough for an artwork to decay? I imagined him saying.

That said, death or rather loss, is central to John Paul’s work. Be it the loss of artistic integrity ‘sold’ in exchange for greater audiences, or the detachment from tradition and historicity, the loss of space, of meaning, of connection, of singularity and silence, all shed light on the artist’s dissatisfaction with the general spirit of the contemporary age, disillusioned as it is that the infinite may indeed be reached the further it moves away from the past. But in loss, what ought to be found or desired becomes all the more clear. A story of hope fills my mind; like the young Telemachus awaiting his father’s return – assumed by many to have long been dead – I could also imagine John Paul looking out to sea, waiting patiently, meditating deeply in silence, before finally returning to the studio to begin working on a new piece.

‘Silver River’, an exhibition of works on paper by the Maltese artist John Paul Azzopardi, opens on 30 of October at Lily Agius Gallery. The opening event is sponsored by People & Skin, La Bottega Art Bistro, Fiorente, Artpaper and Logografix Express. The exhibition runs until Saturday 16 November. For more information contact Lily on (+356) 99292488 or go to www.lilyagiusgallery.com.