A Mediterranean Meraviglia: Malta’s National Pavilion

This year's Malta Pavilion, Diplomazjia astuta, has been quite the journey and no small achievement, to say the least. It is curated by an international team led by Keith Sciberras (Malta) and Jeffrey Uslip (US). It features a collaboration between artists Arcangelo Sassolino (Italy), Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci (Malta) and composer Brian Schembri (Malta). It is overseen by project managers Nikki Petroni (Malta) and Esther Flury(Switzerland/USA).

Malta’s National Pavillion is commissioned by Arts Council Malta (ACM) and is overseen by Romina Delia, Internationalisation Associate at ACM.

Charlie Cauchi met with some of the team behind the pavilion to talk through the genesis of this daring installation and what to expect from this trans-national team.

“Well, murder can be art too.”

A line uttered by Brandon, John Dall’s character in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 thriller Rope may seem like an odd point of departure to discuss Malta’s upcoming national pavilion at the Venice Biennale. But if we scratch beneath the surface, there’s an undeniable link.

It was a murder that first brought Michelangelo Merisi, or Caravaggio, as he is more widely known, to Malta. He descended upon the capital Valletta in the early 1600s, a disgraced fugitive. The Southern Italian encountered a fortified landscape, newly constructed only 40 years prior. Valletta was the seat of power for the Order of Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem. It may have been a modern city back then, but its geometrical streets were a backdrop for insurmountable violence and gore. Its golden limestone walls were drenched in blood.

A year after his arrival, Caravaggio was initiated into the order and commissioned to create what would become one of his most significant works and the largest canvas of his career: The Beheading of St John the Baptist. Some suggest that his masterpiece is an admission of the artist’s own guilt. The painting itself is preoccupied with a violent act – a brutal execution. More importantly, if you look close enough, you will note that the name “Fra Michelangelo” is scrawled in the blood that drips down the martyr’s neck. It is one of the only paintings that the artist signed himself. Graffiti, Seicento style.

This deep red drop of blood sparked the imagination of artist Arcangelo Sassolino. It is in this blood that this journey begins.

Fortuna Critica

February 2022, only two months to the opening of the Biennale, and it is my turn to wander through the grid layout that makes up Valletta. I am on my way to meet Professor Keith Sciberras, co-curator of the Malta Pavilion. The cacophony of a modern-day crusade accompanies me – bloodshed has been replaced by a heady mix of consumerism and culture. On my way to the Valletta Campus of the University of Malta (UoM), I walk past St John’s Co-Cathedral, the Baptist’s permanent residence. A handful of tourists sit opposite, sipping their espressos at Cafe Caravaggio. The iconoclast may have left, but he still looms large over the city. How, I wonder, will his work be incorporated into our national pavilion?

Keith is quick to answer my question. This installation is not about Caravaggio, he explains, but about re-situating him in a contemporary framework. The work is in dialogue with Caravaggio’s Beheading, deliberately redefining it through contemporary art aesthetics and practices.

The British-Mexican born artist Leonora Carrington is the inspiration behind the title of this year’s edition of the Venice Biennale. The surrealist drawings featured in her book The Milk of Dreams depict a magical world of transformation and change. Venice Biennale curator Cecilia Alemani, drawn to the otherworldliness of Carrington’s work, has explained elsewhere that this year’s edition is “a deliberate rethinking of man’s centrality in the history of art and contemporary culture.” In many respects, Diplomazjia astuta is rooted in a similar narrative. Sciberras notes that likewise, the Malta Pavilion is preoccupied with utilising the history of art to speak a contemporary language: “It is a project of contemporary aesthetics. The entire team’s work is a collective intellectual effort, using contemporary mediums to capture the aura of Caravaggio’s work.“

As a core component of the team, Keith brings with him extensive knowledge of Caravaggio. His main research area is, after all, the Seicento. However, it would be rather simplistic and do him a great disservice to think of him only as such. “The role of the art historian includes so many things: curating, formal analysis, art theory, technical art theory, art history, mathematics, materiality, contextuality. This all bridges stylistic periods, so I obviously can’t simply say that I am Seicento scholar without saying that I am an art scholar and an art historian first and foremost.”

Sciberras is especially interested in how art can bridge one period to the other, and Diplomazjia astuta is the perfect vehicle to do just that. As he explains, he is “particularly concerned with the way contemporary artworks engage with the past, how artists of the past have featured or will feature as artists of reference in other works; in what we call the fortuna critica. The fortuna critica concerns the way artists referred to earlier artists and their works. This notion is anchored in this pavilion.” Here, Keith reiterates that the artists have “created an installation that departs from Caravaggio and does not mimic his work.”

While the work does not emulate the Beheading, we can say that there are many parallels to the period that the artist found himself working in. The 17th century was a time of exciting discovery, often cited as an unprecedented age of wonder. Many, like Caravaggio, were challenging classical perceptions from an intellectual, artistic and scientific standpoint. Flash forward hundreds of years later, and the artists involved in this year’s pavilion could be said to be doing the same: using innovative techniques to reflect on the past in order to challenge, understand and explain the present. As a result, the pavilion becomes, in and of itself, a site of wonder. Or, as Sciberras succinctly puts it: “The work is a meraviglia“.

The curator expands upon this notion of wonderment, explaining that the piece is not merely decorative but rather something almost otherworldy that leaves the spectator astonished. “Like our own Ġgantija Temples in Gozo [a megalithic temple complex from the Neolithic] or the Egyptian Pyramids, this is a work of wonder. We want our audience to question the mechanics of the piece. In terms of its construction and what it does, a meraviglia has occurred. It’s a brilliant dialogue between science, mathematics, engineering, and art.”

Caravaggio’s masterpiece, therefore, can be said to extend outside the confines of the canvas and the co-cathedral to create a new body of work, one that can best describe as ethereal. “We are trying to capture the aura of this work,” explains Sciberras. “An aura is something powerful and personal that a work of art transmits.”

Before we delve into the metaphysical aspect of this work further, Keith provides more insight into how the idea for the pavilion came about.

A scholar, an artist and a curator walk into an oratory…

The core team had been working on this monumental piece for over three years. It was initiated by Sassolino and Uslip. The artist and curator approached Professor Sciberras to discuss the concept, given his expertise and links to the subject matter. “They had this beautiful idea that played on the drop of blood featured in Caravaggio’s masterpiece.” Keith was immediately intrigued, “but we weren’t initially sure where the project could go.” So a logical first step was for them to visit the Oratory of the Decollato, the home of The Beheading of St. John the Baptist.

The oratory, constructed in 1602, was founded by the Confraternita della Misericordia (also known as the Compagnia or Società della Misericordia). It has served many functions throughout history: as a place of meditation and devotion; for instruction for the novices of the order; and for formal procedures such as investitures, as well as defrocking (as an aside, this is the same place Caravaggio was himself defrocked in absentia, for being a “foul and rotten member” of the Order. And only six months after becoming a knight).

It soon became evident to Sciberras, Sassolino and Uslip that if their project were to grow, it would have to do so outside of the confines of this sacred space. “It was at that point that we realised that Malta’s Pavilion is the same size as the oratory,” Sciberras explained, adding that this serendipity pushed them to focus on a project that could be transported to the Arsenale.

Once the decision was made to focus on a bid for the national pavilion, the three recognised that they needed to expand their concept and their team. Keith elaborates: “It was at this stage that we acknowledged the fact that we needed a contemporary art theorist, someone who works with a textual based art form. And I couldn’t think of anyone better than Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci. I was already working on a project with him, and I was sure he would be a valuable part of a project that had, at its core, contemporary aesthetics of the Mediterranean. We also realised that the project could benefit from a percussive score and needed a musician, and that’s when Brian Schembri came into the mix. So technically, we have a Seicento scholar, a contemporary art curator, two contemporary artists, an art theorist and a conductor.”

Giuseppe is the first to admit, however, that Keith is the linchpin in this collaboration. “I rarely participate in group activities,” he candidly explains, “but I was persuaded and roped in by Keith. He succeeded in building up a team, each having his and her particular function, and which together, I must say, evolved into quite an exciting venture.” Brian was also hesitant, claiming that he initially thought he was to consult on the score: “I just thought I was to give them some feedback on some musical aspects for this magnificent project and naturally, discussions ensued. Unsurprisingly, as a result, ideas kept coming back to me, and little by little, I was brought on board to compose a score according to the ideas that were coming out from our discussions.”

At first glance, the three artists may seem to form an unlikely collaboration; however, they share many artistic concerns and connections. “This has been a mesmerising collaboration, “Giuseppe explains. He has worked with Brian before, and “obviously enough, we have been ‘collaborating’ for over half a century,” he adds with a smile, reminding me that they are, in fact, siblings. “Whereas I have been working with Arcangelo for a little less than a year, but the chemistry worked out excellently. The three of us, consciously enough and at the same time unawarely so, are underlining rhythms, pauses, intervals, silences, beats, and waves. Each in his way but essentially complementing the dissonance and harmony ensuing, without, however, ever confronting the result.”

So, what are we to expect?

Chapelwith a lower case “c”

The work, according to Keith, is multi-layered and experiential: “We are working on a project that will provide a space for reflective immersion, so it’s not just about what one sees but about what one feels. The pavilion is a space for reflection.” There are also explicit references to injustices throughout the work, epitomised by the drop of blood of the martyr who dies unjustly. We call it a chapel with a small “c”. A sacred space that goes beyond religions.

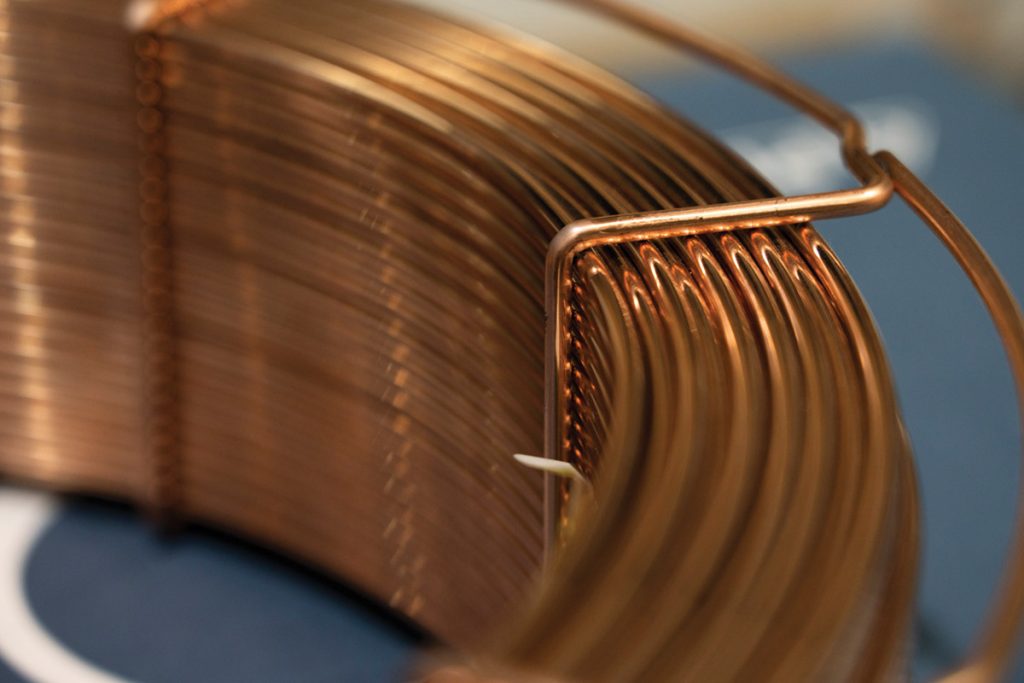

Arcangelo utilises extremely modern media to convey this. His work uses a mixture of induction technology, electrical systems, steel and water to form the kinetic structure that forms the backbone of the pavilion. In addition, the installation takes into consideration environmental concerns. “In terms of the way it functions,” adds Sciberras, “we are making sure that the project is entirely covered by green energy, and that has been part of our remit from day one.”

Ordinarily, the baroque seduces us with folds of fabric, theatrically rippling into the darkness. But here, the luscious language of textile is replaced by the coolness of steel, a medium favoured by Arcangelo and one worked on by Giuseppe. Giuseppe talks about his part in the process, with his task to “challenge” the metal that forms this installation, constructed by Arcangelo. As he puts it: “I was given a sort of aesthetic blank-cheque, and to which after several meetings, versions, bozzettos, preparatory work, I came up with a fascinating final solution, modestly enough I am so excited about, that encapsulates the whole structure into one of spirituality and modernity. Metal and language.”

Language is essential to Giuseppe, using it to unite all these metallic points. The artist and theorist wanted to reinforce the idea that “language is not just one of the means, but the means whereby truths are concealed, to be unconcealed, manifested.” To achieve this, he delved into the multi-culture richness of the Mediterranean languages: Aramaic, Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Arabic, all with sound expertise provided by Dr Rev. Edgar Vella, and Dr Rev Paul Sciberras, to name a few.”

Samuel Becket has also heavily influenced the artist’s work, and interestingly enough, there is a connection between Beckett and Carravagio. Giuseppe tells me he found this out when he first encountered Becket as a student. “While the author was in Malta, he was suffering from problems with his eyesight. In a letter he writes to Josette Hayden, he tells her that his eyesight was miraculously restored after a visit to the Beheading of Saint John. This may be a little dramatic, but I find his experience in Malta a fascinating point in his life and work, and he used his experience in Malta to develop his “spewing of words”.

Words are not the only form of language integral to the pavilion. Music is just as important. Brian created a project-specific score to accompany the installation. He refers to this as “percussive because there will be no definite pitch musical notes heard. There is going to be a particular sound production and there is going to be a visual element which goes with the sound being produced.” Arcangelo’s sculpture has been elevated to a unique instrument with Brian’s expertise.

It was up to Schembri to find a way to musically organise the visual and a sonorous effects emanated by Archangelo’s work into a score. “As discussions developed, I understood that Caravaggio’s masterpiece was the central theme intertwined with Giuseppe’s engraving. From these different pieces of information, I had to come up with some sort of musical connection. I needed something to grasp at, something which could help me lay a foundation for further development of my musical ideas. I understood that the number seven was an important aspect of this project because there are seven characters in Caravaggio’s ‘Beheading of St John’, and the installation is based on this number as well.”

Scibberas outlines another component of the pavilion that many may not be aware of, and that is its educational programme: “The educational aspect of this pavilion is also extraordinary. Several groups are being immersed very directly and very profoundly into the mechanics of international contemporary art.”

Forward Looking

To learn more about the programme, I spoke to Dr Nikki Petroni, part of the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Malta. Nikki works alongside Esther Flury to manage the pavilion, but the educational programme falls under her remit. I asked Nikki how she came to form part of the team. Her role, she informs me, can be seen as somewhat of a natural progression to a long-standing collaboration. UoM alumni herself, she was initially one of Giuseppe’s students, reading for her PhD under his supervision. “We have since worked on multiple projects together. Keith was also one of my professors, and now we are colleagues.”

She explains that the educational programme targets a variety of individuals. For Nikki, one of the most exciting aspects of the programme is a study unit geared towards 25 students reading for a BA within the Department of Art and Art History. “This is the first time this unit will have a contemporary art focus. The students on this unit will also spend time at the Biennale, completely immersing themselves in a world of international contemporary art.”

Not only does this degree credit provide them with the opportunity to learn about the broader narrative of the Biennale, but they will also have the chance to interact with the key individuals that form Malta’s Pavilion. “So, for example,” Nikki expands, “Jeffrey Uslip will be able to impart his vast experience of curation in the USA and Europe through a series of seminars. And they even visiting Arcangelo’s studio in Vicenza. So, these students aren’t just going to the Biennale. They are going to see what happens behind the scenes and to see the studios of one of the biggest contemporary artists in Italy.”

A group of curatorial assistants made up of recent UoM graduates, graduates and undergraduate students re also being offered the chance to form an integral part of the team, spending time working at the pavilion. Nikki points out that the opportunities for these students are immense: “First of all, from a professional point of view, they are being exposed to the highest level of contemporary art practise, curation and management, from both an international and national perspective.” Besides this, there is also the ability to network in a very international context, where they get to meet curators, gallerists, spectators. As she sees it, “while at the pavilion, these assistants are our ambassadors. They must present our pavilion to anyone who asks about it.”

In addition, 14 Erasmus students from the UoM and the Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology are also participating in the programme.

However, What most excites Nikki is that the scale of the opportunities offered to Maltese students is continuously increasing. “This is beautiful to witness. I remember being so happy when I was a BA student because there was a tiny gallery that gave me a little job. I remember being so proud because working in an actual gallery.” I ask her how it feels to have gone from there to forming part of the curatorial team for Malta’s National Pavilion. “Everyone starts somewhere small. Not that many years ago, though, it was so limited, but I am still so grateful for that little opportunity.”

However, Nikki is part of a movement helping to turn those “little opportunities” into something more impactful:” I feel that the scope of what we are doing is also very long term. I hope that many of these students will continue to study further. However, the most significant impact will be on the University programme itself. Thanks to the pavilion, the contemporary art section within the Department of Art and Art History is continuing to grow, adding to the dedicated work under Giuseppe’s coordination over the past few years.”

It would be remiss to think that the programme only caters for those in academia. Nikki maintains that the general public is also a key demographic: “Our outreach also expands outside of academia, both in Malta and Venice, through a series of satellite events that will run concurrently throughout the Biennale.”

This progressive way of thinking encapsulates the spirit of Diplomazjia astuta. I may have started out contemplating death and destruction, but this work defies us to consider the very essence of our being. Sciberras is also interested in what happens beyond this year’s offering, ” pushing the boundaries of what a pavilion can do and where it can go.” Through Diplomazjia astute, he set out to help create something different: “I am hoping that together we can show a way for future pavilions”.