Make Some Noise

Do artists in Malta do enough to highlight the pathetic state of our land abuse and construction rampage policies? Does anybody care?

Malta is on an uglification spree. It has become a bulldozers’ paradise and is rife with every form of pollution. Our levels of noise pollution, for instance, are nauseating – and yet for the man on the street, construction noise is more tolerated than music. Laughter is not. I’m generalising here, but I believe that, for most, the idea of wide open space seems to be a newly inaugurated five-lane road, or a car park. We like the colour green on a wall, or the plastic plants on the ceiling of a new American fast-food chain. We enjoy the little countryside that’s left from our car windows. Landscaping here is understood as the act of laying travertine down so that we can stroll on it pushing prams and buggies covered in plastic with children inside. We prefer to cut down 300-year old trees so that their roots don’t crack the surrounding tarmac and we won’t have to clean after the birds that roost in them. We like birds to be dead and stuffed. It’s dystopian. Pathetic.

“Many Malta-based artists have produced powerful works to express the pain they feel when witnessing this environmental apathy, highlighting the cause….. BUT ARE WE LISTENING?”

In this regard, my exasperation at the callous disregard for the environment, which has gone beyond indifference towards a delusional justification of destruction for the ‘greater good’ of greed, leaves me speechless. So perhaps I’ll let the art speak for itself.

Many Malta-based artists have produced powerful works to express the pain they feel when witnessing this environmental apathy, highlighting the cause – the blatant destruction of the natural environment and the rampage of the construction industry. But are we listening?

“It’s art, it has a strong voice it can project, and with it the potential to change perceptions and catalyse emotion. Artists work within the sphere of wider society given they are part of it. How amplified that voice becomes is up to them, but it is nonetheless part of public discourse and they do perturb the system every now and then.” Says established contemporary artist Pierre Portelli, whose own practice has engaged consistently with environmental issues as well as other contemporary social issues.

Discussing the launch of EarthSpeakr when asked what can be done to balance our economic needs with the well-being of the people in an interview with Laura Swale in The Times of Malta in July 2020, artist Olafur Eliasson said “I could recommend a few things, still. Put an artist on every board of every company, put an artist in every political meeting room, put a child in every government advisory board, put a young person in every evaluation board about the impact of what they’re doing. Integrate a just choice of people”.

So, I looked back at the recent work of several artists exhibited in solo or collective exhibitions to refresh our collective memory; tapping into the force of powerful works that scream to our core.

ĦUDHA (Take it) was a collective pop-up exhibition with works that represented the sentiment of the prevalent ‘take what you want’ attitude in relation to the local environmental consciousness. It brought together thirteen visual artists, each of whom brought their own statement based on the current environmental situation in Malta.

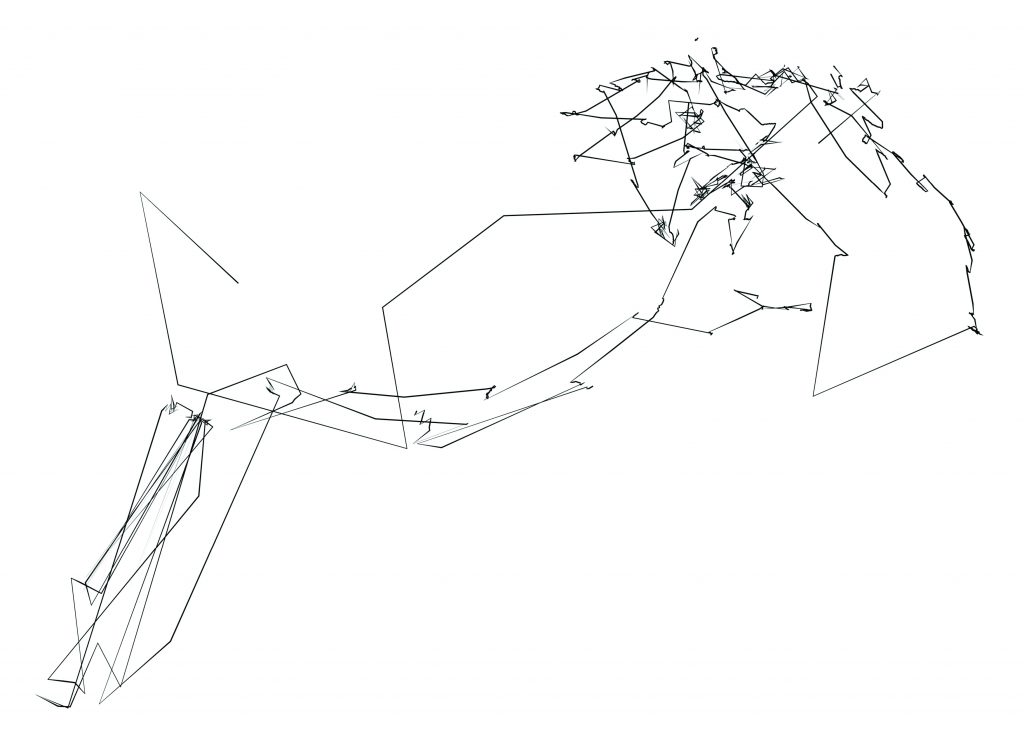

I was particularly struck by new on-the-scene artists like Alessio Cuschieri and his Maltese Quarry/ashtray and Yan Pirotta’s Distorr. The last work refers in part to the distorted information we receive – where we are shown parts of a whole out of context and, in the words of the artist himself, “we force ourselves to believe for the ‘greater good’ of a country, but it turns out to be a force of greed”.

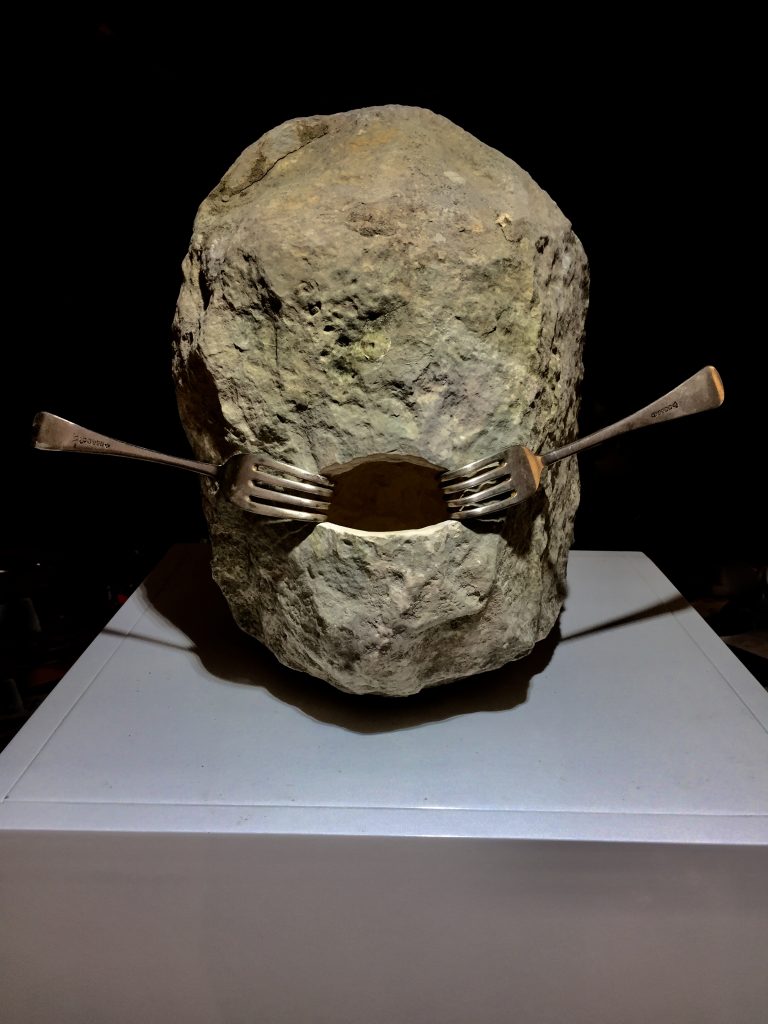

IBLALIBA, by Pierre Portelli, is a strong visual comment on the gluttonous avarice of uncontrolled land speculation. “The forks here become implements that stretch the buccal cavity in an attempt to over ingest. In this work I chose to represent an oral cavity, whether it is a head or not, it is up to the viewer”.

In her significant body of work, and as per her essay on islestotheleft.org, artist Charlene Galea talks about How the sea has become Malta’s only pavement. How staring at the horizon over the sea is the only way to escape the rampage and the destruction and the only way to absolve us and allow us to connect with nature. In general, Galea’s topics relate to owning the trash that is left in painfully over-developed spaces. The raw imagery contrasts the luxury of what is about to become of that ‘stolen’ space in the future.

“I started going for long walks and documented [what I saw], immediately drawn to the heaps of rubbish on the pavements and the construction sites always digging and piling. That is when I started to focus my research on urban landscapes, the Anthropocene and how we humans live. I collected whatever rubbish I could and created digital collages which later have been presented in St James Cavalier, 2019 an multi-installation called Is-Salott”.

Her fascination with over-development on hysterical levels continued with her project Bodysuits, sneaking girls into construction sites when the workers leave and taking over the space as a playground. “Our bodies playfully climbed cranes, fell in the cement and posed seductively in these spaces”. This project was presented in Arles and as well in Malta in her exhibition, Hudha.

Recently in her project Island Girls, presented in Vienna in Kunsthalle Enexergasse, Galea took a model to a huge construction site that was half filled with water and they pretended it was a sea spot in Malta. “What most images like to do in art is relax not disturb. When I create collages, I try to have a sense of humour and portray something akin to prettiness in all the ugliness with a funny title. But a selfie of me looking sexy gets triple the attention than any of these collages”.

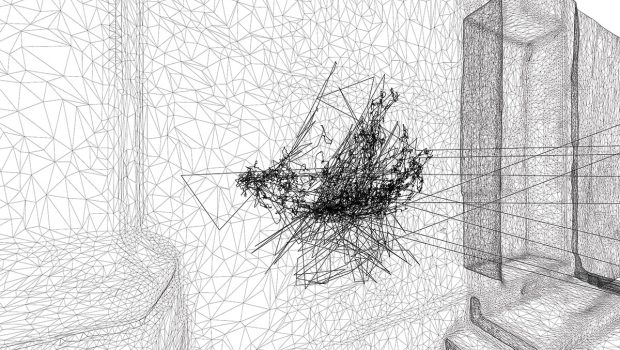

Matthew Attard’s contribution to Hudha took the form of a number of ‘eye-drawings’ that started from the common perception that having a house plant is enough for a sustainable way of living.

“Of course, in no way is the work meant to discourage anyone from living with house plants — the highlight is on how important they are — but also on how they cannot stand alone in face of an unsustainable development on a bigger picture. The drawings are a bit of a satirical pun on this: the act of making them derives from directly looking at the plants, which looking is being translated by the eye-tracker into data points (from which I then post-produce the drawing). I also liked the idea of having something that it purely organic represented through a digital process, which can raise interesting questions and comments in itself.”

Attard has been working on other works dealing with environmental issues. “Using the eye-tracker as a medium for drawing, also means that the captured data is ‘witnessing’ what one sees”. I am certainly looking forward to seeing more of this.

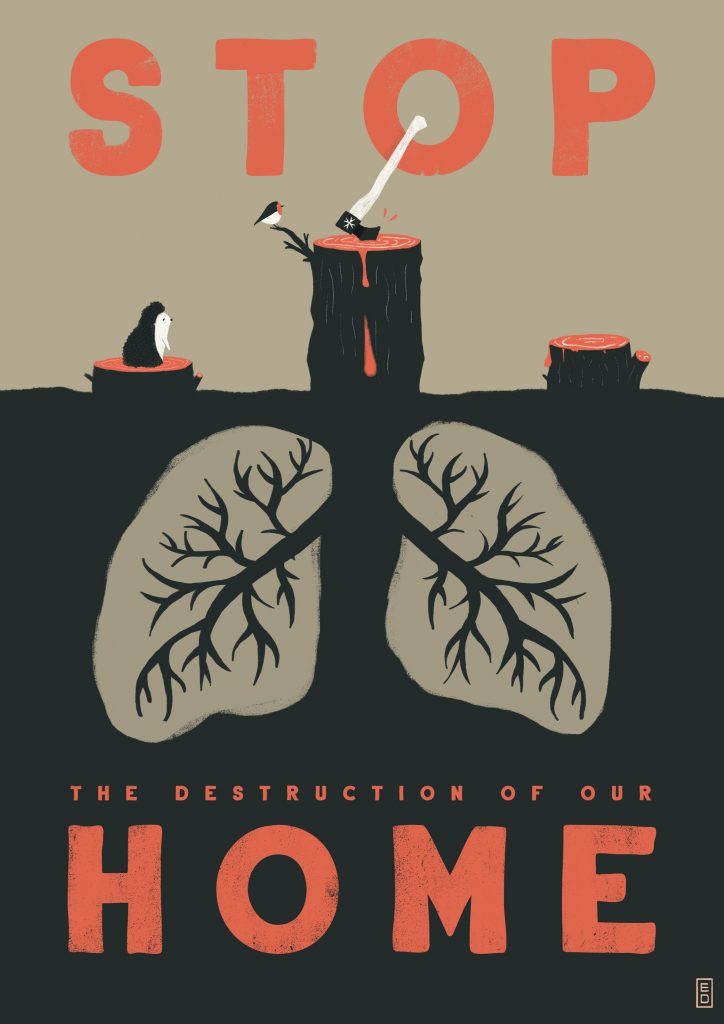

ARTNA, a poster exhibition, was a project set up by a newly-formed community of creative illustrators who felt compelled to join forces and create a response to the extreme frustration felt over the unsustainable over-construction and general disregard for the environment by successive administrations and the general public. Malta lacks guerrilla and street art examples, both of which are usually deemed controversial by our mostly conservative society.

The illustrators were encouraged by the increase in awareness and amount of young people getting involved in protests, and created a set of posters that were available for anyone to download, print out, take to protests or paste up as a form of demonstration. The public was urged to join and support local NGOs who work tirelessly to lobby the authorities on a range of related issues.

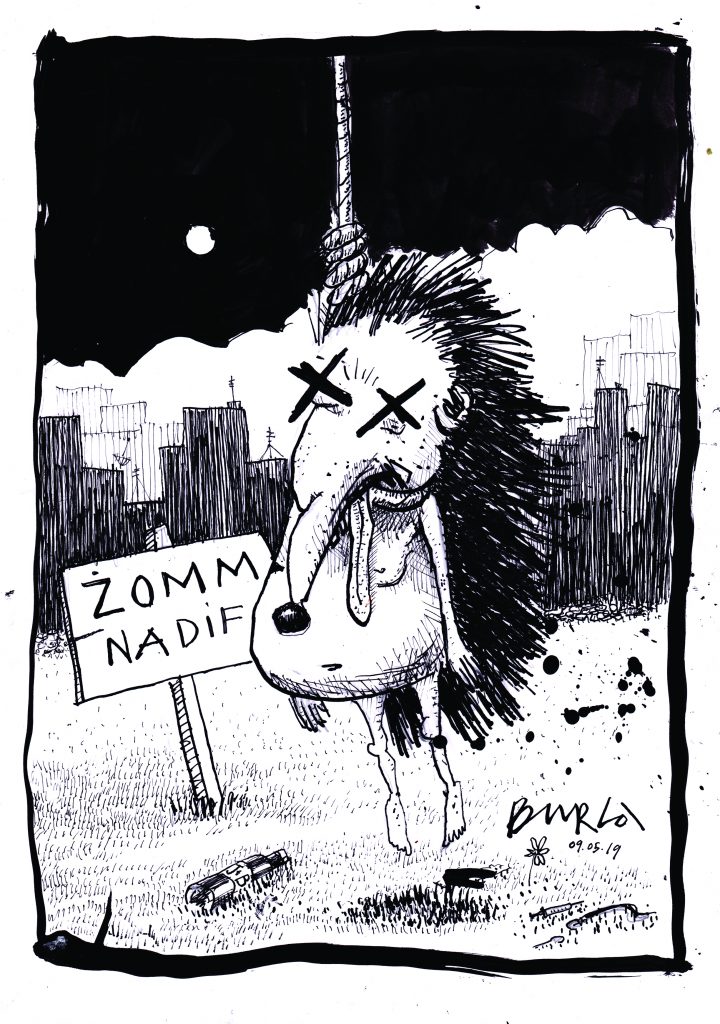

Seb Tanti Burlo’s And in the end the hardest thing for Xummiemu was to find a tree... is incredibly powerful. Ed Dingli, the project’s organiser says, “with today’s oversaturation of images, it’s up to the creativity of the artist to get their image seen and their voice heard beyond their echo chamber, but getting support from entities, organisations and publications is vital in helping to spread awareness to a wider audience. In my opinion, one of the main problems contributing to the unsustainable development is the sense of apathy among the public, and general unwillingness to hold the authorities to account. We see something that upsets us, react with a sigh or a shrug, and quickly move on to something else. What we really need to do is harness that frustration and turn it into something productive – and that was essentially the impetus behind the idea for Artna”.

Dingli continues to remind the authorities that the local artists’ community, for instance, have been lobbying collectively for empty public heritage buildings to be assigned for artist residencies and creative communities and not be given away to commercial entities. The artist is trying hard to raise the bar of collective consciousness and if support is not forthcoming, the artist is suffocated. As Yan Pirotta says, “my voice is usually silent, but loud when exhibited – leaving a breathing space for the viewer to judge on his own.”

An artist must engage with society. As Pierre Portelli says, “changing perceptions requires persistence and creative energy and in my case through soliciting proactive and participatory engagement of the viewers of my work. If viewers engage positively, neutrally, negatively, actively or passively, then it’s an opportunity to engender an interaction. It’s where the possibility to initiate some change in perception and bring about an emotive response occurs”.