Enzo Mari’s timeless lessons

The opening of the retrospective at the Triennale (Milan) sadly coincided with the passing of the great Italian designer, Enzo Mari, whose work will always remind audiences of the importance of rigour and seriousness, as well as the infinite opportunities for beauty that accessible, modest and truly sustainable design offers.

As philosopher Hannah Arendt once wrote, spatial thinking is political thinking, and so was design thinking to Enzo Mari. Above anything else, to him design was a way to understand the world, to learn about environments and people, and to express a specific, democratic, almost utopian, vision of ‘things’. The notoriously stern and short-tempered Italian designer influenced the industry at large with his uncompromising views on what design is – or should be – about.

with Elio Mari, silk-screen print on texilina paper, 112 x 112 cm, Danese Milano. Photo Danese Milano

Enzo Mari genuinely cared about striving for equality through design and contributing to society in meaningful ways.

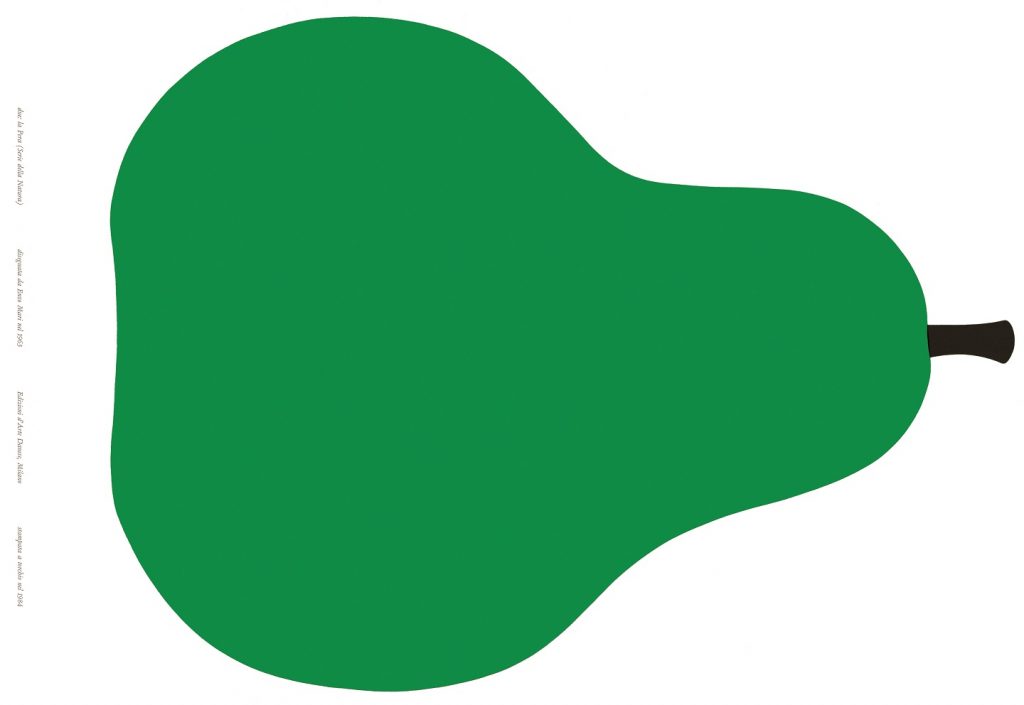

Among Mari’s vast production of design objects, or things, as was his preferred term, the publication Autoprogettazione is perhaps one that best illustrates his vision. It was first published in Italy in 1974, at the time of Enrico Berlinguer’s most inspired speeches, and initially often underestimated as a dull DYI manual. On the contrary, the book is a guide to experiencing design processes, infused with art, politics and a great deal of empathy.

Autoprogettazione is hard to convey in English; as explained in the introduction to the most recent edition, “It literally means auto = self and progettazione = design. But the term ‘self-design’ is misleading since the word ‘design’ to the general public now signifies a series of superficially decorative objects. By the word ‘Autoprogettazione’, Mari means an exercise to be carried out individually to improve one’s personal understanding of the sincerity behind the project. To make this possible you are guided through an archetypal and very simple technique. Therefore the end product, although usable, is only important because of its educational value.”

In 2004, at the peak of the process that saw the design market giving in to formalism, with manufacturing companies becoming glamourous places ‘filling up with yuppies, dangerously replacing genuine entrepreneurs’, he dryly placed a paid advertisement in Domus magazine, turning the template of a standard job advert into what reads like a (still) very valid manifesto. “A good project requires a passionate alliance between two people,” reads the first footnote to the main text, “a soldier of utopia (the designer), and a tiger of the real world (the entrepreneur). The tiger is always the one holding the power to realise at least a small fragment of utopia. Tigers seem to have gone extinct today”. With this ‘inserzione a pagamento’ – worthy of the most cunning Duchampian artist – Enzo Mari asserted the importance of the role of the designer as someone who gives form to a collective value, and the role of the entrepreneur as the crucial figure who makes that form, and therefore that value, accessible to all.

He also methodically investigated the relationship between art and design, which culminated in his exhibition, L’arte del Design, at the Galleria di Arte Moderna in Turin, in 2008; in an interview about it (available on YouTube and highly recommended to Italian-speaking readers), he tells the journalist that the commercialisation of design is now similar to that of contemporary art: “limited edition or ‘unique’ design pieces are now being exhibited in galleries and sold at ridiculous prices, as if they were art pieces; but the designer who makes an ‘artistic object’ from time to time, for purely marketing and commercial reasons, shows that he or she knows nothing about art. Art is total desperation”.

This kind of sweeping statement made Mari internationally famous, loved by some and hated by others, but respected by all. He rejected design as a discipline trying to superficially imitate art, or, even worse, aiming at creating beautiful objects for the sake of it – l’art pour l’art. He always remained faithful to his beliefs. For this reason, another famous Italian designer, Alessandro Mendini, dubbed him “the conscience of design”.

At times, Mari may have appeared too harsh or too angry, even intimidating, but that was because he cared. He genuinely cared about striving for equality through design and contributing to society in meaningful ways. He belonged to a generation of intellectuals who witnessed World War II, considered suffering a hallmark of seriousness, valued work as the most noble activity, and wouldn’t think twice before rejecting a job for a matter of principles. These traits, along with a peculiar way of challenging contemporaneity and of resisting its steamrolling commodification-of-everything dynamics, are evident in all of Mari’s projects.

His pioneering work (he was talking about sustainability and circularity long before the terms became buzzwords) inspired not only generations of architects and designers, but today’s most successful artists and curators as well, including acclaimed Hans Ulrich Obrist, co-curator with Francesca Giacomelli of the current retrospective at the Triennale. The exhibition examines over 60 years of Mari’s activity and includes a series of contributions from international artists and designers. Among others: Adelita Husni-Bey, Mimmo Jodice, Adrian Paci, Nanda Vigo, and Virgil Abloh for the merchandising project – which, I believe, Mari himself would have loathed.

Unfortunately, at the time of writing the Triennale is closed due to a new COVID-19 outbreak in the north of Italy. Digital tours and online events have been organised, and more information and regular updates are available on the Triennale website.