Phenomenology of the Pinterest architect

Pinterest has never attracted as much attention and media scrutiny as the likes of Instagram and Facebook, but that doesn’t mean that it’s less controversial and influential, especially when it comes to design and architecture. By Erika Giusta

Pinterest places itself somewhere half-way between social media and search engine. In this fantastic place, architecture is organised in boards, labelled by themes. A theme can be anything, from ‘Decadent interiors’ to ‘Irregularly stacked boxes’, everything is accurately categorised and tagged with a number of key words. Key words rule and define. The chosen combination of key words generates the project’s visual references on the basis of calculated criteria. When typing ‘hotel’, for example, some of the options given for more key words that will define it further are ‘modern’, ‘minimalist’, and then ‘minimalist and luxurious’, or ‘modern and cosy’, and so on.

Suggestions for the most common associations of words populate the screen in what becomes a mix ‘n’ match of bi-dimensional, formal references. From time to time, images with words appear and more sophisticated matches are made by algorithms. In other cases, unexpected combinations can pop up: when choosing to combine ‘architecture’ and ‘happiness’, for instance, one lands on mid-century modern architecture photos and palettes of tilted mirrors. ‘Architecture, solitude’ instead, leads to beautiful German castles, black and white photos and line drawings. The game can be played in reverse too. It can be puzzlingly easy to guess what words were inserted into the Pinterest search bar when looking at a new café fit-out, or at the image used as illustration for an architectural competition brief. It all depends on the magic words inserted in the search bar, at the top of the screen.Those words lay the foundations of a sequence of statistically successful associations of colours, shapes and compositions.

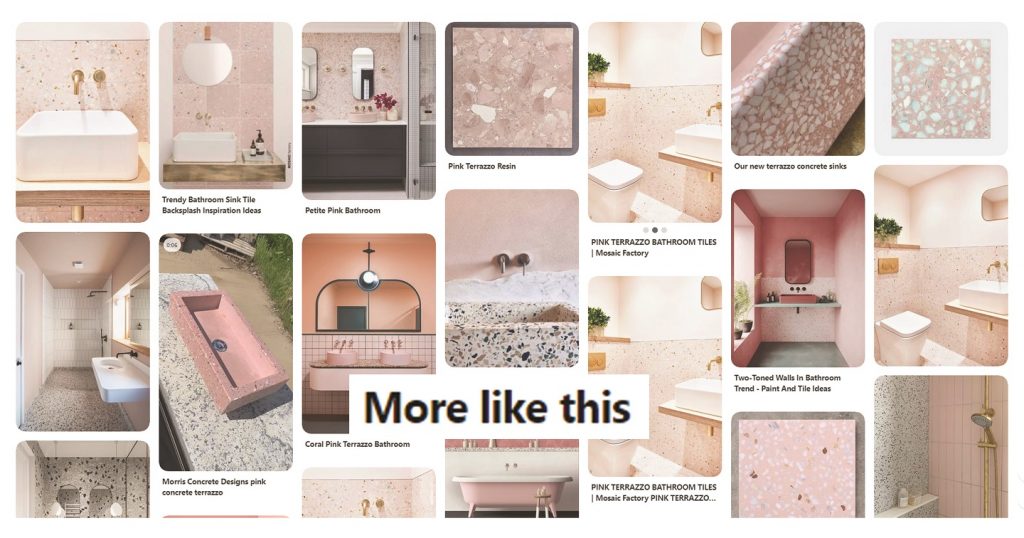

When selecting an image, when pinning it, more recommendations of similar contents pop up; by selecting to associate ‘architecture, happiness’ to ‘coloured tilted mirrors’, for instance, one is suddenly thrown into a whirlwind of pastel colour bathrooms, pink terrazzo tiles, pale green velvet armchairs, photos of dreamy ethereal interiors that have no name, no date or place –they are just there, fluctuating. These images are there to be copied, reproduced ad infinitum, and they declare it explicitly with their captions – or the lack thereof. What counts is the series of tags, not the authors of a project, and even less so the context of what is shown. Inspiration has never been so standardised. One begins to wonder if they are the actual work of humans or machines.

The more an image is pinned on somebody’s board, the more it will be proposed to other people in search of, in this case, the secret to a happy place for themselves or their clients. After this kind of exploration of the platform and a first selection of images, when going back to the homepage, one finds more of the same: ‘more like this’ says the algorithm, before pouring out another cascade of pretty pictures. There’s no break from pink terrazzo tiles in elegant anonymous settings. The suggestions are endless. After a while, the repetition of the same type of images begins to hold a certain fascinating and soothing effect. If it wasn’t for the bias of the (still fallible) algorithm, which, on the basis of gender and age, disrupts the pink terrazzo reverie with Pins on ‘How to apply eyeliner’ and ‘Relationship advice’, the platform would be almost persuasive enough to convince you to abdicate your responsibilities as architect, and just Pin your projects away.

Thanks to the lack of sensitivity of the machine though, the game ends abruptly and even provokes some embarrassment for having indulged in the frivolity of those simplistic shortcuts to the untangling of the complexity of architecture – let alone of happiness! – at least from the very personal perspective of the aspiring phenomenologist running the experiment. If the way Pinterest is experienced can so greatly vary from architect to architect, what is certainly more objective is the fact that its use is widespread at all stages. Many of us rely heavily on it, for a number of reasons, compulsively collecting insane amounts of random images determined by algorithmic calculations on the basis of what is statistically more successful from a purely formal and commercial point of view. The result is loads of architects currently copying the same image without questioning its qualities, reproducing it like mere ‘builders of pretty pictures’, contributing to rendering the profession irrelevant. All the automated calculations at the origin of so many mood boards and projects presentations belong to the marketing world, not to the complexity of the discipline, that – as with any form of knowledge – should be developed and implemented through scientifically valid research.

When the process of production of architecture starts as a purely visual, flat and trivially commercial exercise, it can only end up in another version of that thing. It becomes equally meaningless, but much more damaging, as it transcends the confines of the virtual world to leave a negative impact on the built environment.